Colonial Power Relations and Totalitarian Mass Communication in Half-Life 2

A detailed analysis of Half-Life 2's impressive and historically important digital dystopia

Twenty years have passed since Half-Life 2 was released, and today we can safely say that this is one of the most influential FPS games of all time and one of the most important video games of the 2000s, alongside ICO (2001) and Braid (2008), in a decade that was a turning point in independent and personal video game development in the industry. In this context, Half-Life 2 is also a game with personality and innovation, although not an "auteur's work", but the result of "collective design", which corresponds to Valve's principles (their works usually don't even have detailed credits). Its impressive game design stand out in so many aspects that it would be impossible to cover them all in sufficient depth in a single essay, so it seems a good option to dedicate this space to its narrative design, which, unlike its physical and level design innovations, remains unparalleled and timeless in its way of immersing us in a carefully crafted totalitarian colonial science fiction setting. The narrative design includes a frequently silent, occasionally propulsive, and sometimes atmospheric sound experience, along with gameplay whose spaces of possibilities are narratively coherent, and whose linear plot is at the same time engaging and non-intrusive in terms of controls.

"The two key words of Half-Life 2, oppression and invasion, come from the dictatorial regime of my native Bulgaria. For me, when I was young, the militia and the army meant the forces of evil."

Viktor Antonov, Half-Life 2 art director (interview with Antonov in French, L'1nterview, 2019)

"From my first visit to Valve, I had many conversations with people who shared my vision of integrating narrative and level design - specifically, how you would make that architecture do your storytelling. I only wanted to think about the FPS experience. It just seemed the most involving and interesting for narrative, because it put you right into the middle of a story the way a novel did."

Marc Laidlaw, Half-Life 2 writer (interview with Laidlaw, Rock Paper Shotgun, 2023)

From left to right: The monument in front of Sofia Central Train Station, Bulgaria; the Citadel concept art by Viktor Antonov; the Citadel and some apartments in City 17, Half-Life 2. Sources: Reddit; Combine Wiki; Valve.

After the events of the first Half-Life, several space-time rifts similar to the one that began the Half-Life series appear on Earth and allow aliens from Xen to invade and start the Seven Hour War. Among these alien forces are the Combine, an intergalactic empire that eliminates almost all other invading aliens (with a few exceptions, such as the antlions that built underground structures) and establishes a colonial agreement with Earth mediated by Dr. Breen, who was the former administrator of the Black Mesa Research Facility in the first game and afterwards became the UN representative to negotiate peace. About twenty years later, Gordon Freeman awakens from stasis and returns to City 17 on Earth, one of the numerous cities controlled by the Combine forces. For those who have not yet played Half-Life 2, you will not find much more in this essay about the events of its plot other than what is in this paragraph. Only in the third section of the essay are there some minor related spoilers, but they generally concern the context and only to a lesser degree the specific points of the narrative.

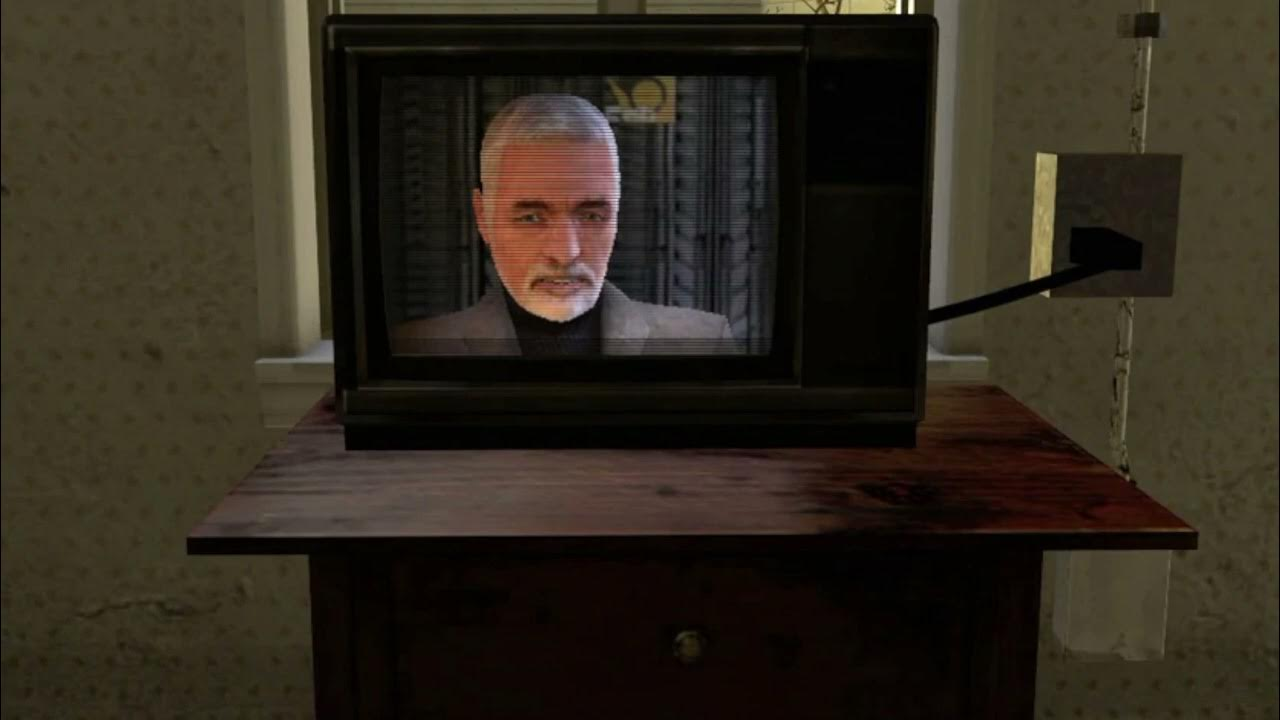

Unlike the Portal series, in which the player has constant, direct and personal communication with GLaDOS, its antagonist, the Half-Life series is characterized by inconstant and indirect communication with the antagonist, the Combine, which is not even clearly identifiable, except through social mediators: in the case of Half-Life 2, mainly through Dr. Breen, who is inspired by the sociopathic prophet Father Karras from Thief II: The Metal Age (interview with Laidlaw, Rock Paper Shotgun, 2023), who communicates to the player through radio shows as he sneaks around on solitary missions.

Left: Father Karras, Thief II: The Metal Age; right: Dr. Breen, Half-Life 2. Sources: Thief Wiki; The Half-Life & Portal Encyclopedia.

Based on this principle of mediated antagonism, the game design of Half-Life 2 mainly discusses power relations and mass communication. This essay is dedicated to examining how these two aspects can be identified and understood within the general rhetorical objective of Valve's game designers.

Table of Contents

I. Choices, Antagonisms and Power Relations

I. i. Freedom to choose and freedom to oppose

I. ii. Power to act and power to influence

I. iii. Playable character and acting character

I. iv. Rebel forces vs. Combine forces

II. Power, Persuasion and Game Design

II. i. Outcome power and social power

II. ii. Second-order relations: which power relations are allowed?

III. Mass Communication and Miscommunication

III. i. Dialogues, media and communication concepts

III. ii. Dr. Breen's discursive strategies

IV. Final thoughts

I. Choices, Antagonisms and Power Relations

I. i. Freedom to choose and freedom to oppose

The mainstream antagonism concept can be traced back to Ancient Greek tragedy. The word “antagonistēs” is derived from anti- ("against") and agonizesthai ("to contend for a prize"), i.e., an “opponent” or a “competitor for a prize in dispute”. For example: Antigone vs. Creon, in Antigone, by Sophocles, who compete with each other for the right to decide whether or not to bury Polynices (which reflects an underlying debate between divine laws and human laws). Although there is an asymmetry of power in this play, both Antigone and Creon are "free", which means that Creon cannot completely control Antigone, and so she can choose to oppose his orders. Freedom plays a fundamental role in a theatrical production, as it does in a game (electronic or otherwise), since a completely controlled or submissive individual is a mere supporting character.

A peculiarity of video games is that they combine these two types of "freedom": the freedom of the player (the freedom to choose) and the freedom of a protagonist or antagonist (the freedom to oppose). The first type of freedom offers playability, the second one, unpredictability. In the following subsections, we will see how these concepts relate to each other in Half-Life 2.

I. ii. Power to act and power to influence

Aristotle's definition of “choice” (prohairesis) seems appropriate to gameplay: Aristotle, in Nicomachean Ethics, defines choice as a deliberate desire for the means to an end (for example, the deliberate desire to finish Chapter 6 of Half-Life 2 using only the gravity gun, in order to get an achievement on Steam); and he defines "power" as a capacity (or dunamis) that is connected with change (for example, the skill and other elements needed for a player to complete Chapter 6 using only the gravity gun). Note that the above examples are metanarratives, but we can adapt these concepts to a fictional context in which we represent characters immersed in power relations. Power relations involve actors that, instead of acting on objects (such as when someone tries to break a supply crate), act on subjects, or, more precisely, act on other possible actions, compromising other actors or denying them the effectiveness of their alternative choices (such as when someone blocks you from going through a door or convinces you to use a new weapon).

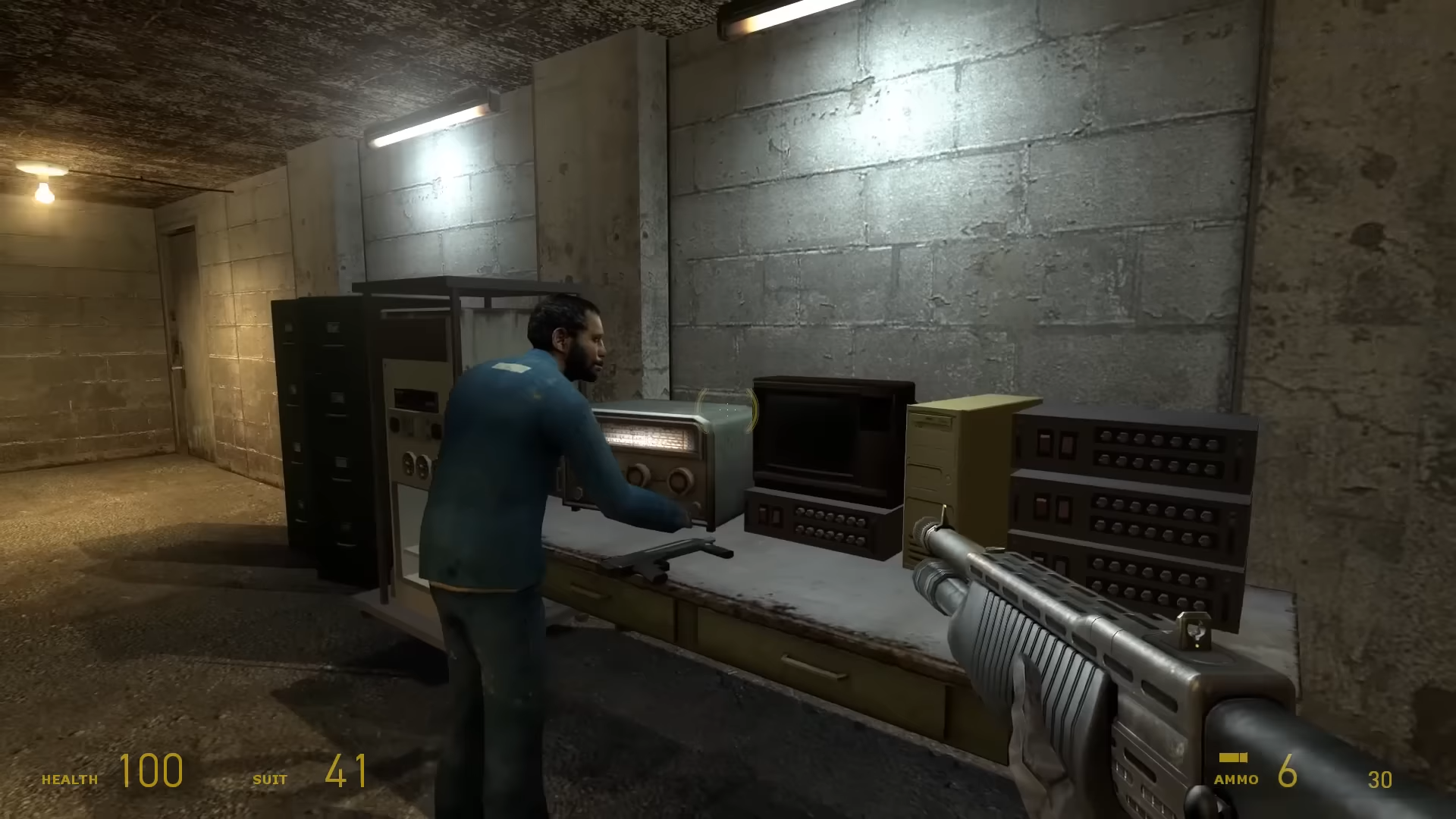

Acting on objects (left) vs. acting on possible actions (right), Half-Life 2. Source: Valve.

When there are choices and power relations between two or more actors, and they can communicate (reciprocally or not), we enter the realm of persuasion and manipulation, which is the topic of analysis in this essay. Manipulation, unlike persuasion, typically exploits a person's weaknesses. On the other hand, influence that is not manipulative is generally viewed as something "harmless" regardless of whether it's accepted or rejected. Both persuasion and manipulation will be the subject of the third section of this essay. However, first we need to detail the structure of power relations in Half-Life 2.

The player chooses, the fictional character acts; in order to choose, there must be different options for action, and, in order to act, there must be power. In this framework, we can take Half-Life 2's context of choice and action into consideration, the context in which the player and the main characters decide the future of Earth. If we use game theory to define the scope of gameplay (noting that this is just one possible approach), we can say that gameplay only exists where there is choice. In each case, game designers will define the scope of gameplay for their game. In the case of Half-Life 2, it is certainly not in its plot; in fact, the only possible plot choice in the entire Half-Life franchise is a decision at the end of the first Half-Life, between two possible endings, where only one of them is canonical.

I. iii. Playable character and acting character

In video games, the narrative experience is not just about the plot, but how the player interacts with it, and in this sense the Half-Life series is more narratively interactive than many adventure RPGs. In the game, the player can not only deliberately interact with NPCs, requesting some response from them, but, while this dialogue is taking place, the player is free to move and look around. In some cases, he will only become aware of certain interactions by deliberately going to a specific place or using some item, e.g., binoculars. The gameplay with the protagonist, Gordon Freeman, essentially consists of two choices: exploration and combat, both of which are always limited. The former is never denied to the player, while the latter is only denied when in front of friendly NPCs, since the player does not have the power to interfere with any of their actions, unlike in the first Half-Life, where, with some exceptions, it is possible to block their passage or even kill them.

Left: Gordon aiming his gun at an ally in Half-Life; right: Gordon aiming his gun at an ally in Half-Life 2. Source: Valve.

This means that the protagonist, as a playable character, is susceptible to power relations in these two domains: exploration and combat; but Gordon, as a fictional character, is presumably also subject to power relations inherent to his role in the plot, as a young and skilled theoretical physicist with legendary feats of survival who carries the high expectations from a rebel human faction to lead them. Although the fact that the protagonist is silent and always controllable blurs the line between this duality, it persists, because there isn't any plot choice.

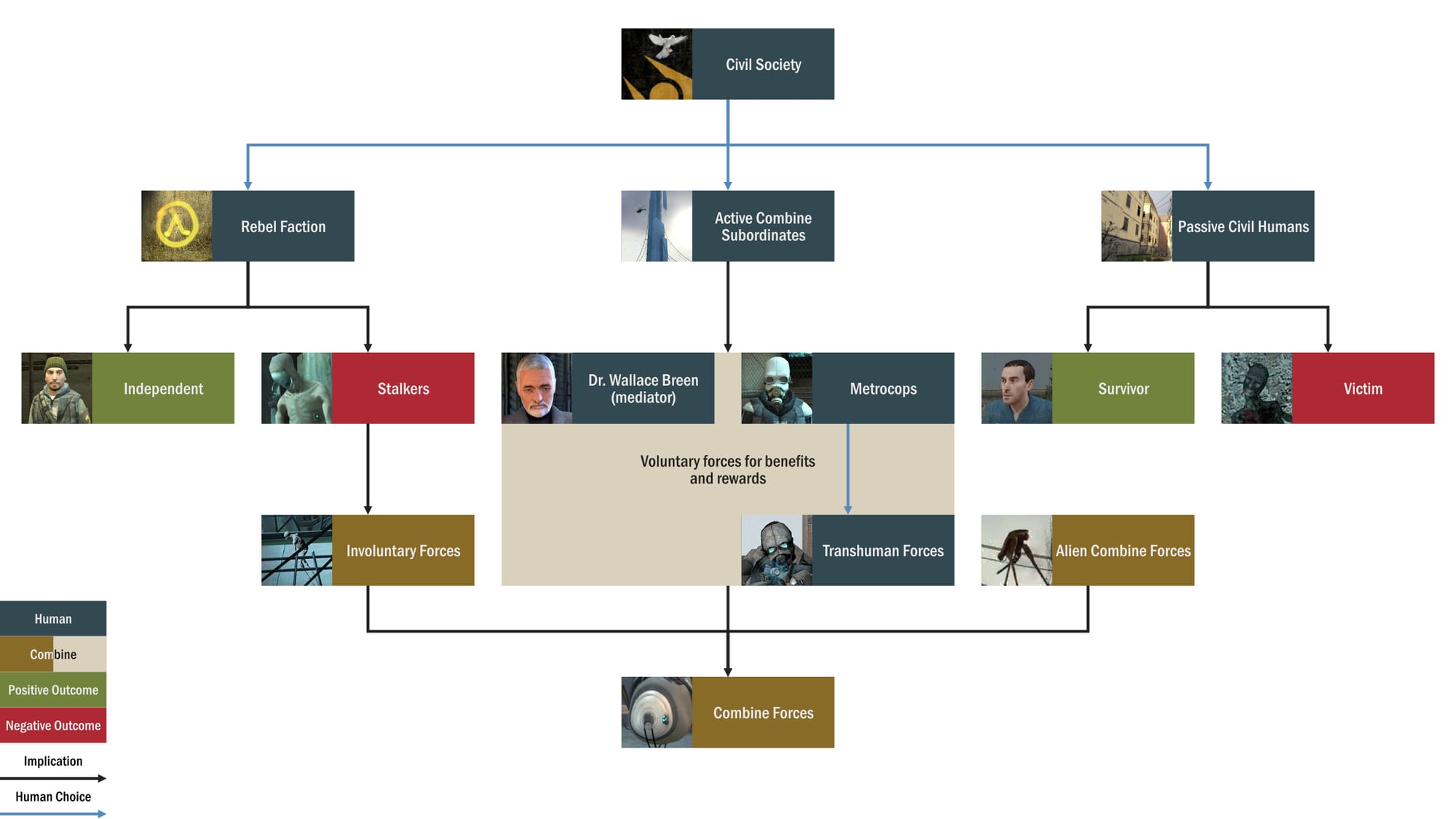

I. iv. Rebel forces vs. Combine forces

The plot of Half-Life 2 can be interpreted as a civil war between two coalitions of actors: the rebel forces and the Combine forces, each with their own internal power relations. In the next section, we will specifically discuss Half-Life 2's game design strategies for power relations and persuasion involving Gordon (both as a playable character and as an actor, in the fictional sense) and also other fictional characters, but first it is useful to establish a map of the relations between them. In this story, we will consider a simplified model with three main human groups of actors on Earth colonized by the Combine:

- Rebel faction: a group of humans who rebel against the Combine forces in order to gain independence for Earth, but who may be captured by them and, after highly intrusive lobotomy and biomechanical surgeries, be turned into "stalkers" (involuntary Combine forces), serving as slaves for maintenance work;

- Passive civil subordinates: a group of humans who resign to Combine rule and submit to totalitarian laws and a ration-based diet, with the hope of survival, but at the risk of going extinct due to a suppression field deployed by the Combine that inhibits the human reproductive cycle;

- Active combine subordinates: a group of humans who, in order to gain rewards and social benefits, choose to join a volunteer police force (metrocops), who are subordinate to the Combine, and, to obtain even more benefits, can undergo biomechanical surgeries and join the Combine transhuman forces.

Other groups involved in the dispute include (1) the vortigaunts, an alien race who survived from the first Half-Life and who ally with the human rebels; (2) synthetic Combine forces, which are highly-modified extra-terrestrial beings used for battle and transport; and (3) the G-Man, a mysterious character who we will leave out of this analysis. Below we offer a summary of the power relations within the framework we proposed for the groups of actors and the possible choices for humans after the colonization of Earth, that is, after the surrender of Earth negotiated by Dr. Breen that ended the Seven Hour War.

The reason the diagram above focuses on civilian humans and distinguishes their voluntary or involuntary subordination to the Combine versus their chance of survival or independence is because we are trying to model power relations around the notion of rational choice. It should be noted that this is an idealized approach, and is not the most natural way of understanding implicit power relations such as those studied by Michel Foucault, and it may also not be the best choice for the vortigaunts and other aliens present in the game, which is why they are not included in the diagram. However, this approach is accurate, elegant, and especially useful for games.

II. Power, persuasion and game design

II. i. Outcome power and social power

In his book, Power, Keith Dowding defines power in a game theory framework, modeling human individuals or groups as “actors” who choose, based on a calculation of reward and probability, one option from a set of possible choices of actions in order to try to achieve a desired outcome. Naturally, an actor’s “incentive structure” comprises their interpretation and beliefs about the probability that each action will lead to the desired outcome and about the costs associated with these possible actions in the choice set. In this context, we will consider from now on two types of power:

- Outcome power: the power of an actor to bring about or help bring about outcomes;

- Social power: the power of an actor to influence the incentive structure, that is, to change the incentives of other actors to bring about outcomes.

In these terms, we say that an actor is "relatively powerful" when he can (1) reduce options in another actor's choice set; (2) change the costs of his options; (3) change the probability of the effect of his actions; or (4) persuade him to change his beliefs. Half-Life 2 teaches us this concept at the beginning of the game, when a metrocop throws a soda can on the ground and orders Gordon to pick it up and throw it in the trash. In this example, it is a power relation by coercion in which the metrocop does not limit Gordon's options (he can decide whether or not to throw the soda can in the trash), does not effect his ability to successfully put the soda in the trash can (if he chooses to do so), and does not try to change his beliefs about whether or not he should do so, but increases the cost of his decision if he chooses to not throw the soda can in the trash: if this is Gordon's choice, he will get beaten by the metrocop, because, at the beginning of the game, Gordon does not have any weapons to defend himself, and he can only try to run away.

Next the game shows us a "friendly" or contractual example of power relations within the rebel faction, when Barney Calhoun, a rebel infiltrator among the metrocops, helps you escape and introduces you to Dr. Isaac Kleiner, who leads Barney's risky mission. These and other forms of power relations permeate the narrative experience of Half-Life 2 and its sequels Episode One and Episode Two, but the most interesting power relations we find are indirect, unlike these last examples involving metrocops. Indirect power relations establish the hierarchies of subordination within the rebel forces and within the Combine forces: the more valuable you are to one of these forces, the higher you may be in the hierarchy, having greater internal social power within your group and possibly gaining more benefits, but potentially foregoing extra protection.

II. ii. Second-order relations: which power relations are allowed?

There are many power relations, some of which may be considered legitimate within the group while others may not be; someone with legitimate power is what we call an "authority", but even an authority can establish illegitimate power relations, which may be condemned within their own group. Presumably, the rules of power relations among the rebels arise from tacit agreements, such as "do not harm an ally", which applies even to Gordon. On the other hand, it is not easy to discover the source of the Combine's power relation structure. Apparently, the Combine's authority, instead of emanating from a "civil consensus" within their forces, is sustained by a military hierarchy, whose superiors are unknown to us.

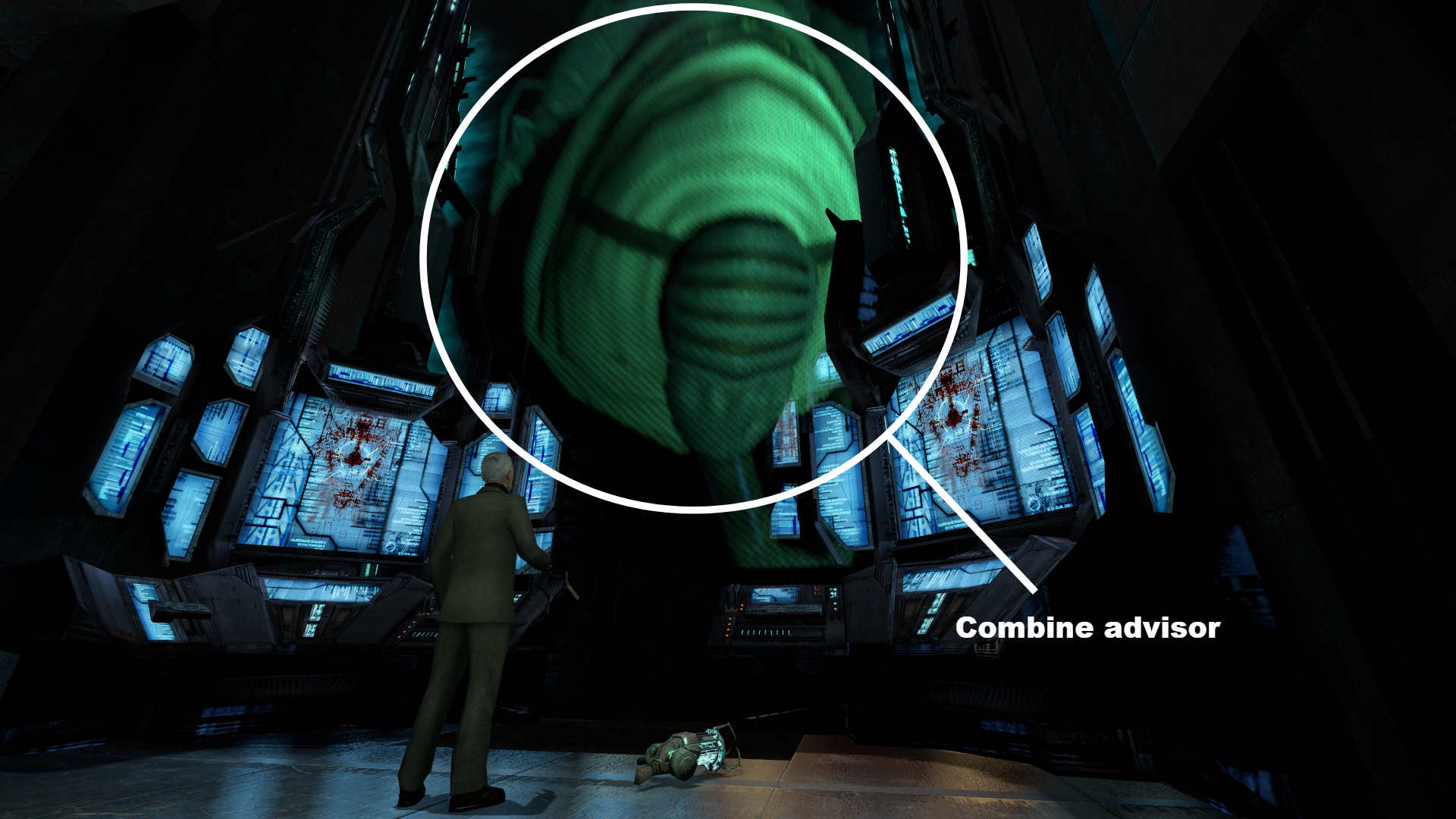

In fact, this is one of the most interesting features of the narrative experience of Half-Life 2: the player is immersed in a game whose masters he does not know; we only know some of the scientific leaders who coordinate the rebels. Dr. Breen answers to Combine advisors, who possibly answer to other beings that are unknown to us. The "chess board" is even more complicated: we know that G-Man is also involved with both forces. However, although the player cannot see the higher authorities behind the game, the pro-human game design choices constantly persuade him to sympathize with the rebels and never with the Combine.

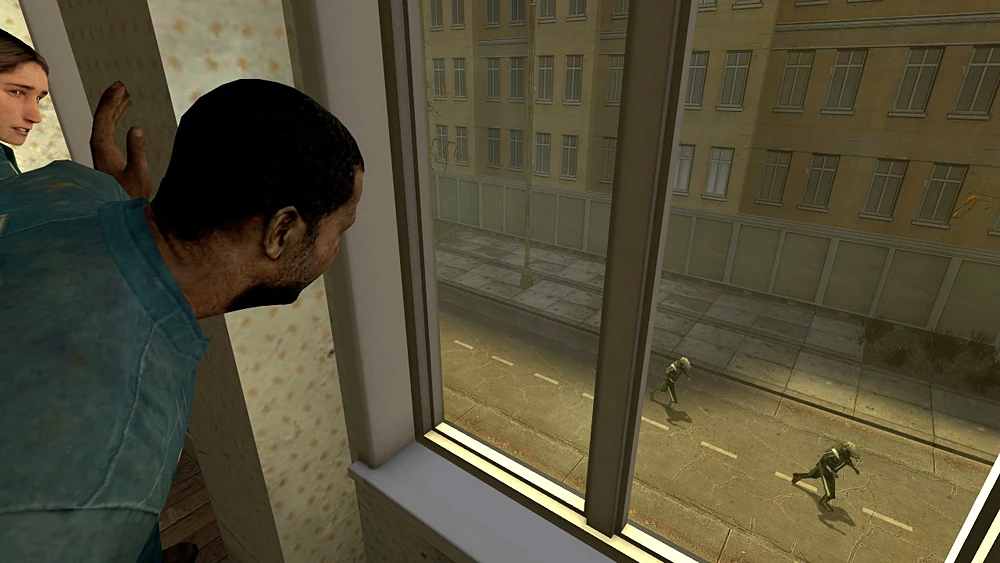

Left: Dr. Breen and a Combine advisor; right: seen through binoculars, G-Man and a civilian inside a house. Both from Half-Life 2. Source: Valve. Edit: Combine advisor and G-Man identification.

Half-life 2 is not a "neutral description" of a civil war between humans colonized by extra-terrestrial forces. Its narrative consists of an interactive process carefully designed with the aim of persuading the player to side with one of the forces in this war and the preservation of "(social) freedom" and "(physical and mental) humanity", even if these terms are not rigorously defined. This rhetorical aspect of Half-Life 2 is not unique, but is in fact a common and perhaps unavoidable aspect of video games as technological media. Ian Bogost, in his 2007 book Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Videogames, coined the term "procedural rhetoric" (or "simulation rhetoric") specifically to encompass this characteristic of video games, which can be observed in many aspects of game design, such as the design of controls, sound, art, interface, and narrative. In the next section we will explore Half-Life 2's procedural rhetoric as it relates to the communication established between its actors.

III. Mass communication and miscommunication

III. i. Dialogues, media and communication concepts

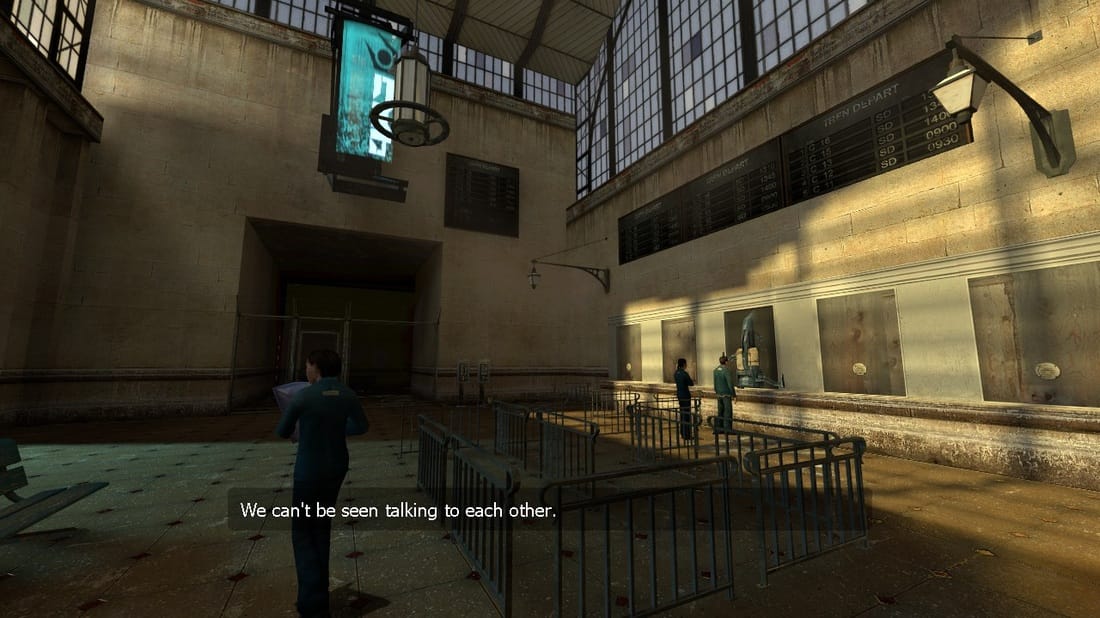

Since the principles of power relations among the rebel forces are presumably governed by civil consensus, communication between its members is horizontal and dialogical, meaning that it is based on the broad possibility of dialogue, that is, on the reciprocal possibility of individuals in different positions to disagree or diverge in terms or nuances, as long as they share the common principles necessary to understand each other and be part of the same group. On the other hand, since the principles of power relations among the Combine forces are governed by a military hierarchy, communication between its members is vertical and imperative, that is, based on a unilateral channel of communication without the possibility of the recipient questioning its sender, when the latter is in a hierarchically superior position. The only exception in the Combine forces is the diplomatic dialogue between Dr. Breen, as the Earth representative, and the Combine advisors; however, it is an asymmetrical dialogue in which Dr. Breen seems to have little or no success in having any of his opinions accepted by the colonizing aliens.

The developers of Half-Life 2 make this difference in communication between the two forces clear, but the narrative design is highly focused on communication with a passive recipient, starting with Gordon Freeman himself, both because the player cannot make any decisions in the plot and because the protagonist does not speak, but merely follows orders; similarly, this is the situation of most of the civilians who are passively subordinate to the Combine forces. Like the other civilians, Freeman will only be able to truly be a "free man" if the rebels win the war.

Both the protagonist and other civilians are passively exposed to Dr. Breen's persuasive and manipulative rational discourses in mass media, particularly via television. In Episode One, which immediately follows the events of Half-Life 2, we see a counterpoint to this discourse via the same medium, by Dr. Kleiner, but in order to limit ourselves to Half-Life 2 as originally released, we will not study this counterpoint discourse. Inactive channels of communication in Half-Life 2 include newspapers, public telephones, and computers: the press was abolished (we only find newspapers published during or shortly after the Seven Hour War), telephone wires were cut, and the internet became inaccessible (we learn more about this in Half-Life: Alyx). In the next subsection, we will analyze Dr. Breen's discourse strategies.

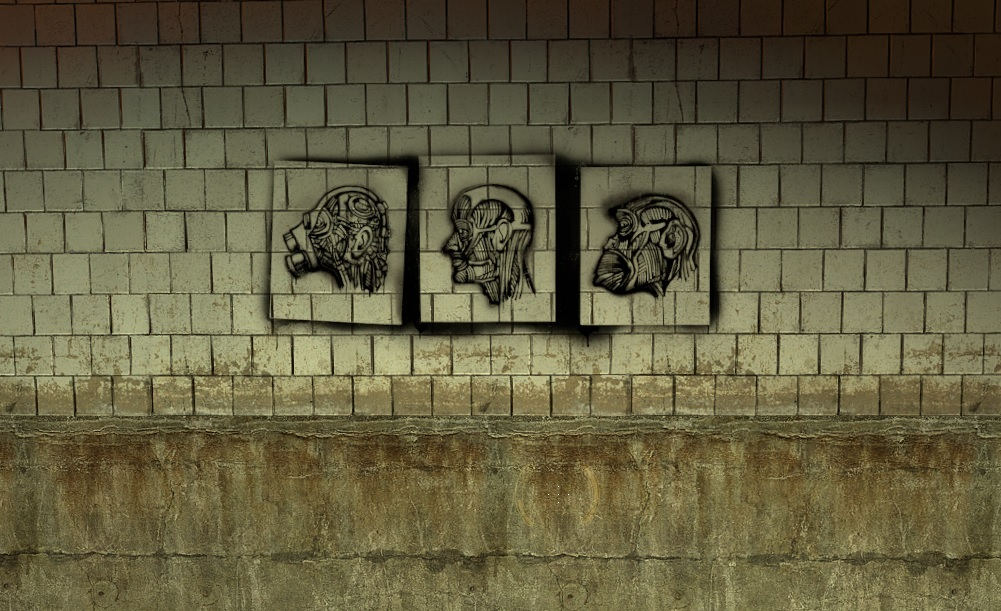

Some means of communication or expression in Half-Life 2: graffiti, public telephone, old newspapers, radio, computer without internet (only with local connections) and television. Source: Valve.

III. ii. Dr. Breen's discursive strategies

Dr. Breen is undoubtedly part of a totalitarian project on a global scale. Unlike an authoritarian regime, which is typically concerned with maintaining its political power and, so long as it does not feel threatened, offers society some degree of freedom and does not aim to change the world or human nature; on other hand, a totalitarian regime, as Hannah Arendt observed, aims to control virtually every aspect of life in society, and promotes official ideologies with the aim of completely controlling the thoughts and actions of its citizens.

There are a number of references in Half-Life 2 to the German totalitarian experience (such as the logistics of the trains, and the appearance and function of stalkers) in a setting deeply inspired by communist post-war Eastern Europe (interview with Antonov, L'1nterview), so it is tempting to compare Dr. Breen's discursive strategies to those of Joseph Goebbels, Adolf Hitler's Reich Minister of Propaganda. However, there are important differences to be considered beyond totalitarianism, such as the issues of transhumanism and colonialism related to the Combine. We summarize these three components of Dr. Breen's strategies below:

- Totalitarian component: Some aspects of human life seem to be of no interest to Combine politics, such as education and art, but these traces of human culture have been virtually obliterated; children no longer seem to exist, because for about two decades humans have been unable to reproduce, and the only remaining means of artistic resistance seems to be graffiti. All other aspects of society seem to be severely controlled, restricted and supervised, such as the economy, science, privacy, and moral values. Because of this totalitarian component, many players and critics draw parallels between Half-Life 2 and George Orwell's 1984, as in Paused Thoughts's essay The Narrative Freedom of Video Games: Orwell, Half-Life and Bioshock.

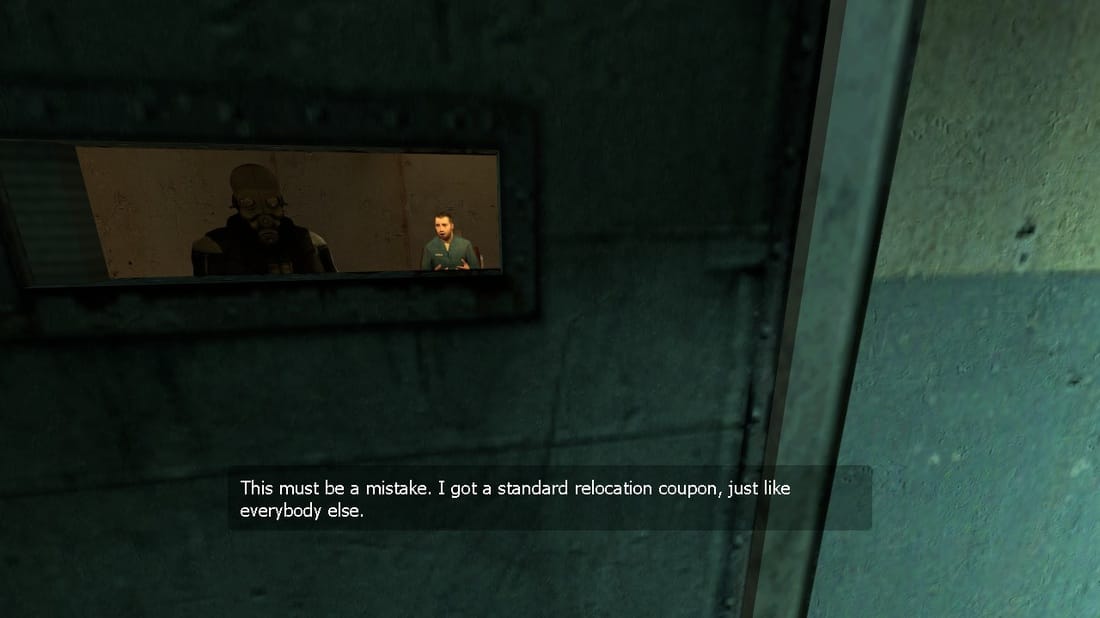

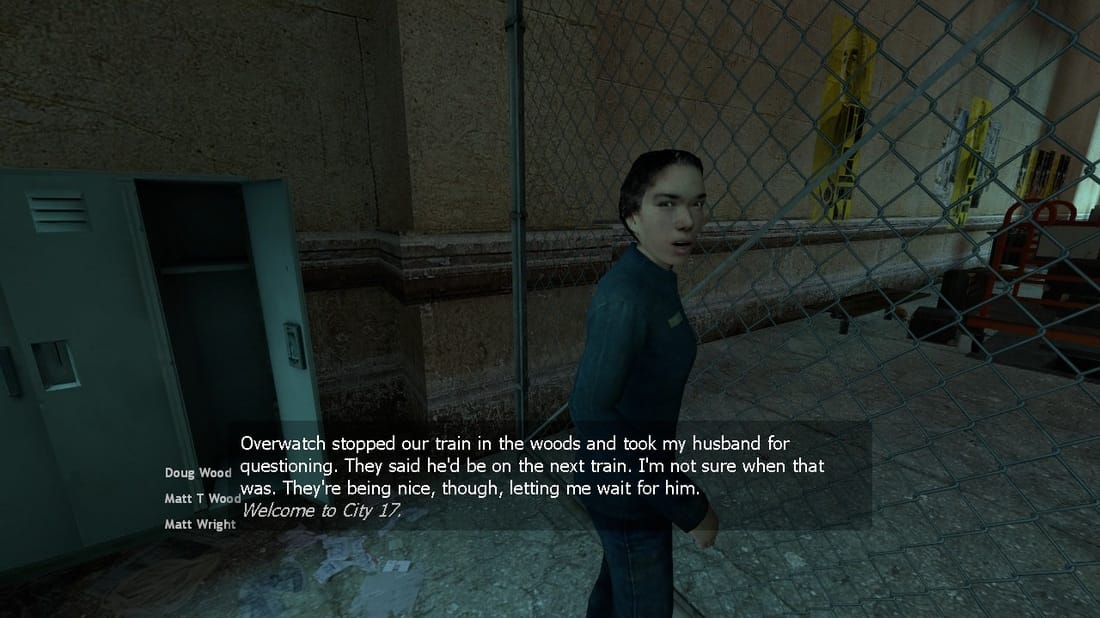

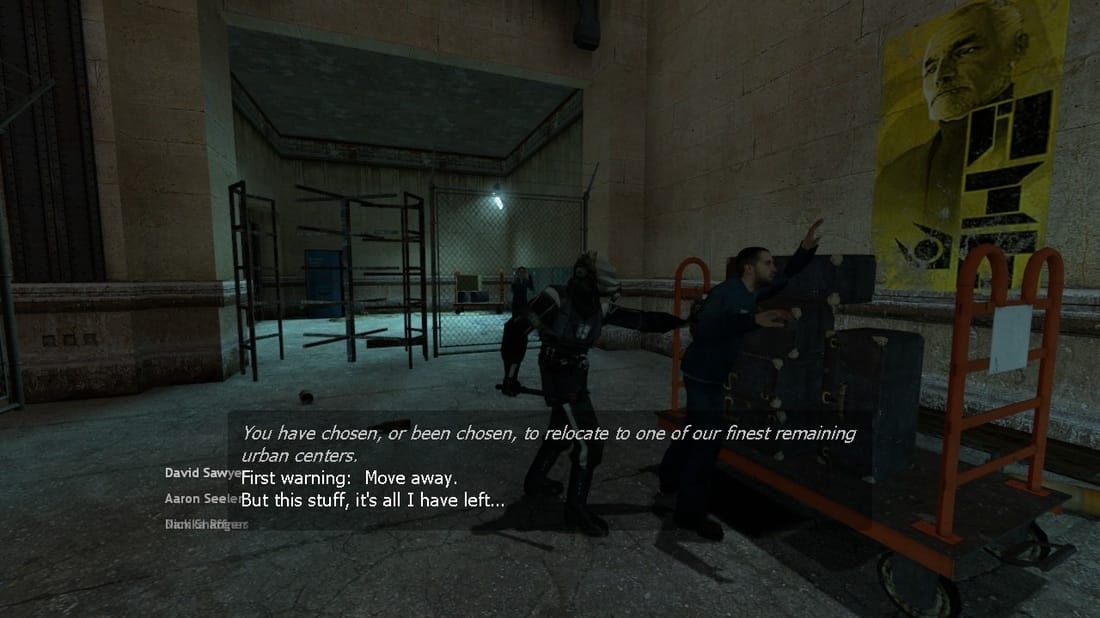

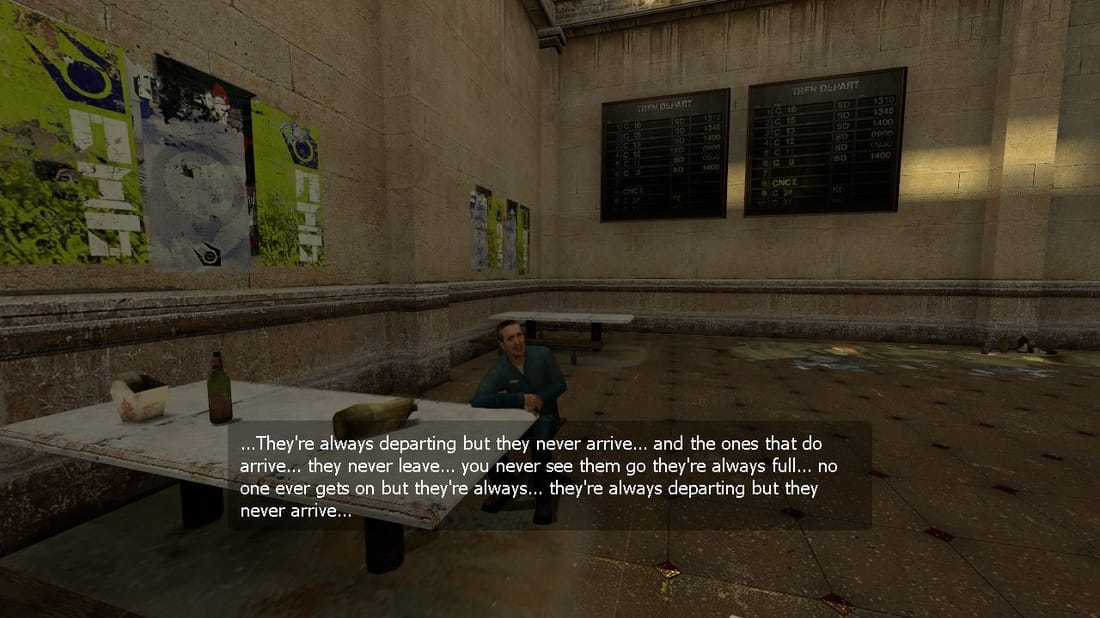

Dialogues in architectural interiors that reveal the social context of City 17, Half-Life 2. Source: Valve.

- Transhumanist component: Similar to the Nazi eugenics ideology advocated by Goebbels, the transhuman ideology advocated by Dr. Breen involves discriminatory attitudes and a physical ideal for the human species, as Dr. Breen gives benefits to those who voluntarily undergo "cyborgization" surgeries, and even more to those who accept to intensify this process. However, ironically Dr. Breen seems to be completely human; perhaps this changed after Half-Life 2, judging by one of the scenes in Episode One.

Left: Prison cells where prisoners who are transformed into stalkers are held; middle: graffiti with a human evolutionist theme; right: body of one of the soldiers of the transhuman forces. Sources: Valve, Otvet.

- Colonialist component: A modern state project is based solely on what Foucault called biopolitics, that is, a set of political technologies for population management, such as public health, regulation of heredity, and regulation of societal risks, among many other mechanisms that go beyond literal physical health. A colonial project, on the other hand, typically involves (at some point in time and in a foreign territory being exploited by the colonizers), what Achille Mbembe called necropolitics, that is, a set of political technologies for the creation of death zones where death becomes the maximum exercise of domination (through the systematic choice of who will die and how) and also the main form of resistance; in this sense, Half-Life 2 takes place from beginning to end in a death zone. Another characteristic of colonialism can be seen in the fact that the Combine have practically suppressed human culture, i.e., human powers to express itself in art and entertainment. Typically, we would also expect the colonists to use slavery or exploited labor, but the Combine do not seem to need humans to exploit Earth's resources, although transhumans have proven useful in military support, as Dr. Breen tries to demonstrate to the Combine advisors.

The contrast in Half-Life 2 between the isolation inside the structures (left) and the violence in the streets (right). Source: Valve.

Evoking these three components, Dr. Breen's strategies mix persuasion and manipulation, in a way that not always makes it easy to distinguish the line between his selfish antisocial behavior and his ideological prosocial behavior, but in his public speeches he seems genuinely convinced of his ideology to protect and perfect the human race at a crucial moment for the survival of the species.

Excerpts of speeches to Gordon:

"A man of science, with the ability to sway reactionary and fearful minds toward the truth, choosing instead to embark on a path of ignorance and decay. Make no mistake, Dr. Freeman. This is not a scientific revolution you have sparked… this is death and finality."

Dr. Breen addressing Gordon Freeman (Broadcast in front of the Overwatch Nexus), full transcript at Combine OverWiki

"[...] Well, I am nothing if not pragmatic. Well, Dr. Freeman, under other circumstances I like to think we might have been able to work together in an atmosphere of mutual trust and respect. [...] Tell me, Dr. Freeman, if you can: you have destroyed so much. What is it, exactly, that you have created? Can you name even one thing? I thought not. I have laid the foundation for humanity's survival, and not as we have narrowly defined ourselves, but as something greater than we could ever imagine. Something we can only now begin to glimpse."

Dr. Breen to Gordon Freeman (Broadcast during Gordon's journey through the Citadel), full transcript at Combine OverWiki

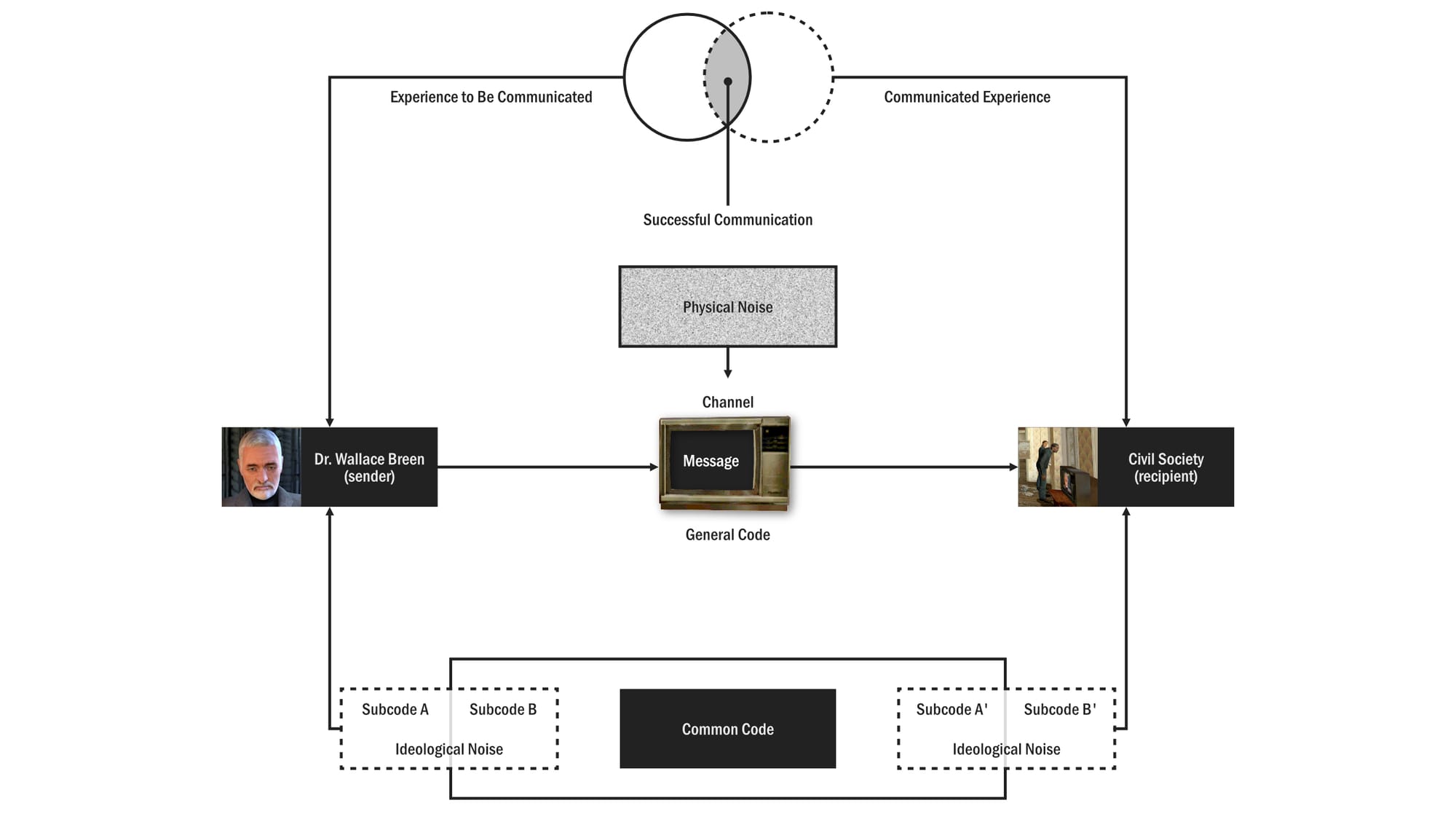

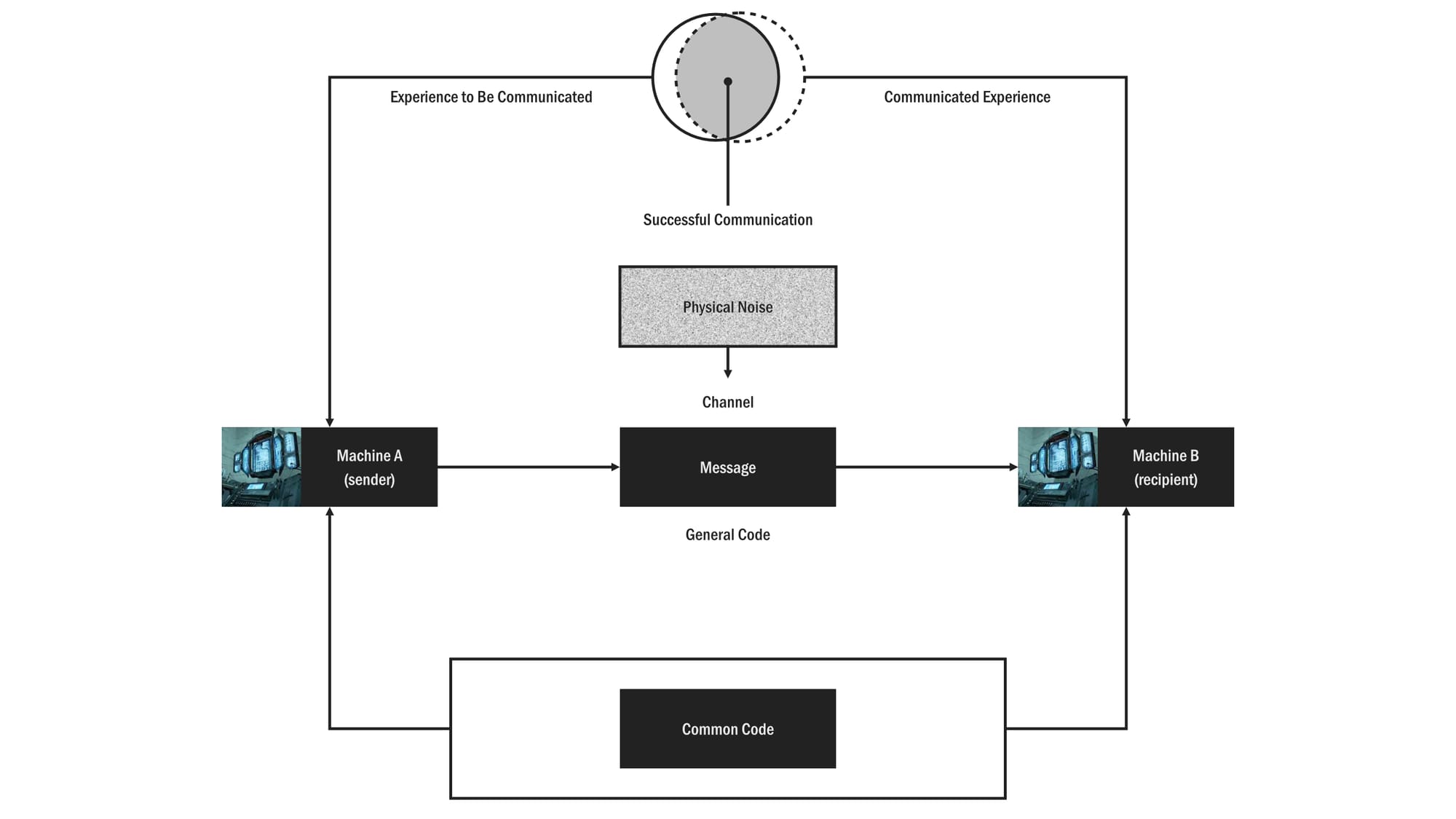

In the public speeches in which Dr. Breen opposes Gordon Freeman, he addresses either the civilian public or the transhuman forces through unanswerable commentary. His communication apparently fails to convince the civilians not to help Freeman. It fails due to the ideological noise of the civilians, their distrust of Dr. Breen, and the growing popular charisma of the rebel movement. The diagram below is an adaptation for this case study of Roman Jakobson's model of communication.

Excerpts of public speeches:

"We now have direct confirmation of a disruptor in our midst, one who has acquired an almost messianic reputation in the minds of certain citizens. His figure is synonymous with the darkest urges of instinct, ignorance and decay. Some of the worst excesses of the Black Mesa Incident have been laid directly at his feet. And yet unsophisticated minds continue to imbue him with romantic power, giving him such dangerous poetic labels as the 'One Free Man', the 'Opener of the Way'. Let me remind all citizens of the dangers of magical thinking. We have scarcely begun to climb from the dark pit of our species' evolution. Let us not slide backward into oblivion, just as we have finally begun to see the light. If you see this so-called Free Man, report him. Civic deeds do not go unrewarded. And contrariwise, complicity with his cause will not go unpunished. Be wise. Be safe. Be aware."

Dr. Breen on Gordon Freeman (Broadcast in the APC garage, in the Canals), full transcript at Combine OverWiki

"I have been asked to say a few words to the transhuman arm of Sector Seventeen Overwatch, concerning recent successes in containing members of the Resistance Science Team. [...] This brings me to the one note of disappointment I must echo from our Benefactors. Obviously I am not on the ground to closely command or second-guess the dedicated forces of the Overwatch, but this does not mean I can shirk responsibility for recent lapses and even outright failures on their part. I have been severely questioned about these shortcomings, and now must put the question to you: How could one man have slipped through your force's fingers time and time again? [...] The man you have consistently failed to slow, let alone capture, is by all standards simply that—an ordinary man. How can you have failed to apprehend him? Well… I will leave the upbraiding for another time, to the extent it proves necessary. Now is the moment to redeem yourselves. If the transhuman forces are to prove themselves an indispensable augmentation to the Combine Overwatch, they will have to earn the privilege. I'm sure I don't have to remind you that the alternative, if you can call it that, is total extinction – in union with all the other unworthy branches of the species. Let's not allow it to come to that. I have done my best to convince Our Benefactors that you are the finest the species has to offer. So far they have accepted my argument, but without concrete evidence to back it up, my words sound increasingly hollow even to me. The burden of proof is on you. As is the consequence of failure. I'll just leave it at that."

Dr. Breen addressing the Overwatch (Broadcast in Nova Prospekt's cell block B4), full transcript at Combine OverWiki

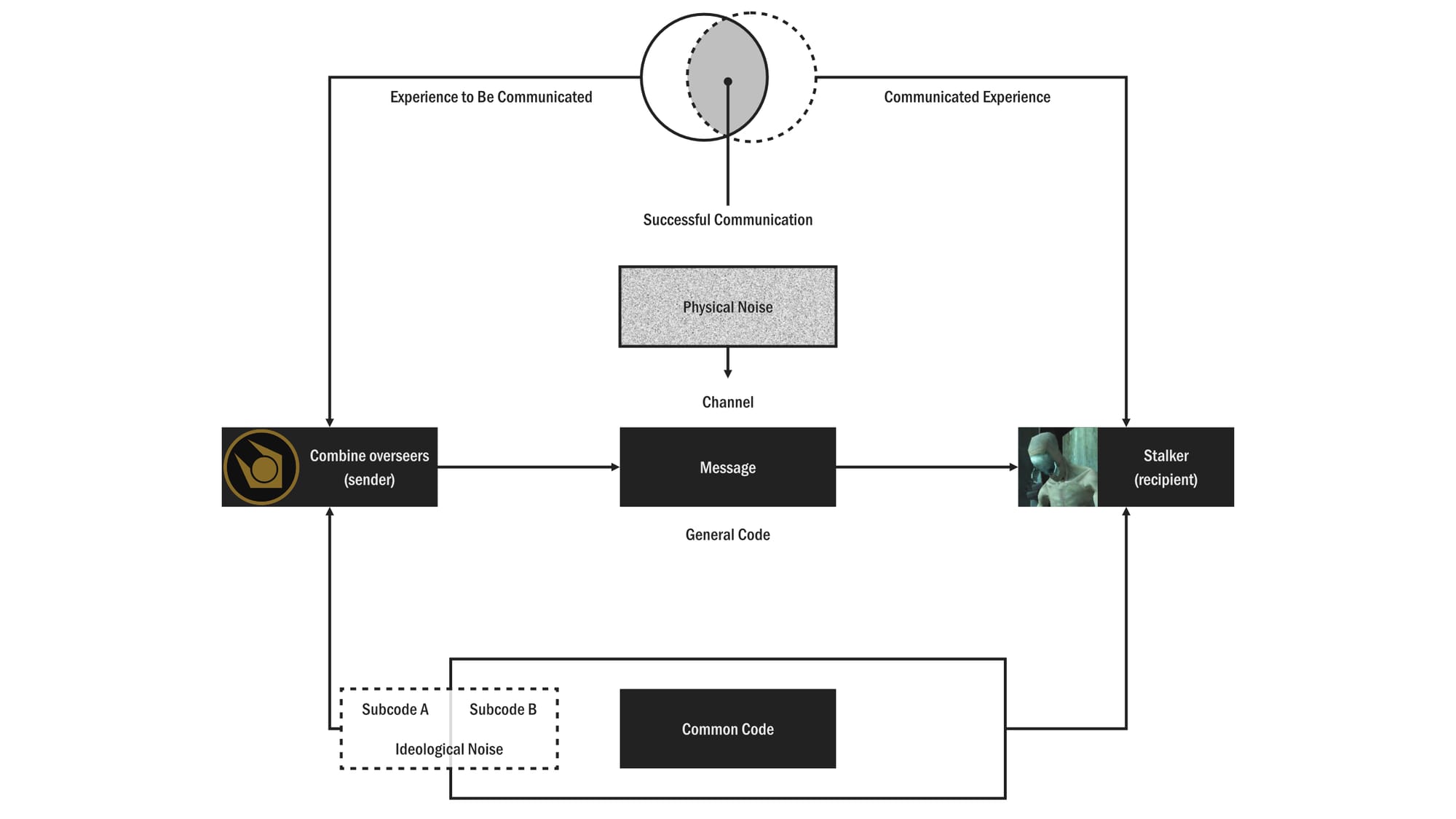

Dr. Breen's solution to miscommunication is to capture the rebels and turn them into stalkers, a process that involves lobotomizing them and giving them brain implants that seem to take away their freedom of opposition and ideological noise, preventing them from having linguistic subcodes appropriate to their thoughts, thus practically becoming machines that respond to a common code. This solution is extreme and complicated to execute, and it is not fully efficient, because there can still be physical noise in the communication (as we note at times in the final chapters of Half-Life 2) and because the understanding (among perhaps other mental abilities) of stalkers is more limited than that of transhumans, which severely reduces their outcome power and nullifies their social power. This seems to be the reason why Dr. Breen keeps the transhumans' minds essentially intact.

In addition to his opposition to Gordon Freeman, Dr. Breen is dedicated to ideologically persuading civilians through mass media. In these public speeches, Dr. Breen maintains a collaborationist discourse between humans and the Combine and presents himself as a rational mediator, and a unifier and protector of humanity with ambitions to evolve a globally organized species in the Universe beyond Earth.

"It has come to my attention that some have lately called me a collaborator, as if such a term were shameful. [...] In our current unparalleled enterprise, refusal to collaborate is simply a refusal to grow—an insistence on suicide, if you will. Did the lungfish refuse to breathe air? It did not. It crept forth boldly while its brethren remained in the blackest ocean abyss, with lidless eyes forever staring at the dark, ignorant and doomed despite their eternal vigilance. [...] In order to be true to our nature, and our destiny, we must aspire to greater things. We have outgrown our cradle. It is futile to cry for mother's milk, when our true sustenance awaits us among the stars. And only the universal union that small minds call 'The Combine' can carry us there. Therefore I say, yes, I am a collaborator. We must all collaborate, willingly, eagerly, if we expect to reap the benefits of unification. And reap we shall."

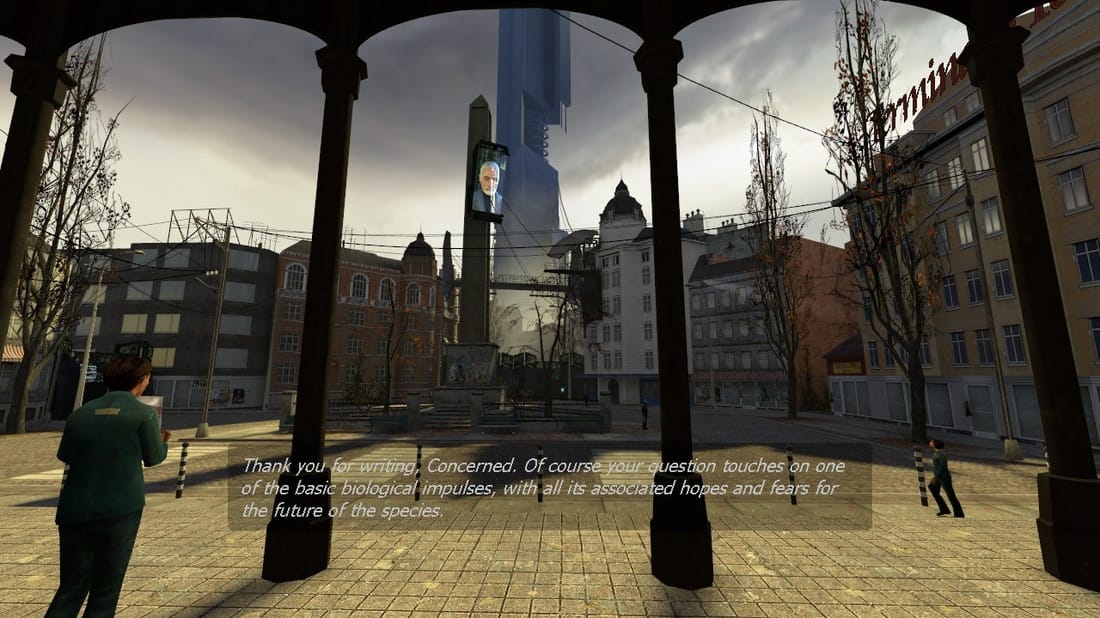

Dr. Breen on collaboration (Broadcast at the start of the City 17 uprising chapters, on the Trainstation Plaza), full transcript at Combine OverWiki

The only time Dr. Breen supposedly responds to any of a citizen's concerns he does not address their immediate material problems, showing a complete lack of empathy in his speech in the face of an extremely violent and oppressive scenario. The question addressed to him is anonymous and written in a manner as unemotional as his answer. In any case, it is interesting to note how his answer reveals his greatest challenge in justifying the Combine's extreme measures, particularly the decision to prevent human reproduction. Dr. Breen's persuasive strategy at this point is systematic and focused on the opposition between instinct and reason, the rejection of instinct in favor of reason, and combined with the promise that the reproductive suppression field will be deactivated soon.

"Let me read a letter I recently received.

"Dear Dr. Breen. Why has the Combine seen fit to suppress our reproductive cycle? Sincerely, A Concerned Citizen." Thank you for writing, Concerned. Of course your question touches on one of the basic biological impulses, with all its associated hopes and fears for the future of the species. I also detect some unspoken questions. Do Our Benefactors really know what's best for us? What gives them the right to make this kind of decision for mankind? Will they ever deactivate the suppression field and let us breed again?"

Allow me to address the anxieties underlying your concerns, rather than try to answer every possible question you might have left unvoiced. First, let us consider the fact that for the first time ever, as a species, immortality is in our reach. This simple fact has far-reaching implications. It requires radical rethinking and revision of our genetic imperatives. It also requires planning and forethought that run in direct opposition to our neural pre-sets. I find it helpful at times like these to remind myself that our true enemy is Instinct. Instinct was our mother when we were an infant species. Instinct coddled us and kept us safe in those hardscrabble years when we hardened our sticks and cooked our first meals above a meager fire and started at the shadows that leapt upon the cavern's walls. But inseparable from Instinct is its dark twin, Superstition. Instinct is inextricably bound to unreasoning impulses, and today we clearly see its true nature. Instinct has just become aware of its irrelevance, and like a cornered beast, it will not go down without a bloody fight. Instinct would inflict a fatal injury on our species. Instinct creates its own oppressors, and bids us rise up against them. Instinct tells us that the unknown is a threat, rather than an opportunity. Instinct slyly and covertly compels us away from change and progress. Instinct, therefore, must be expunged. It must be fought tooth and nail, beginning with the basest of human urges: the urge to reproduce. We should thank Our Benefactors for giving us respite from this overpowering force. They have thrown a switch and exorcised our demons in a single stroke. They have given us the strength we never could have summoned to overcome this compulsion. They have given us purpose. They have turned our eyes toward the stars. Let me assure you that the Suppressing Field will be shut off on the day that we have mastered ourselves... the day we can prove we no longer need it. And that day of transformation, I have it on good authority, is close at hand."

Dr. Breen on instinct (Broadcast in the train station's food hall, on the plaza, and the apartment buildings), full transcript at Combine OverWiki

The main weakness of Breen's communication strategy seems to be his deliberate disregard for human sensitivity and empathy. Unlike Goebbels, who included specific measures for the educational system and artistic production in his Nazi communication strategy, and who added vocal and gestural emphasis with emotional suggestions to his speeches, Dr. Breen and the Combine seem equally ignorant of human nature and human needs beyond their capacity for reason and self-preservation.

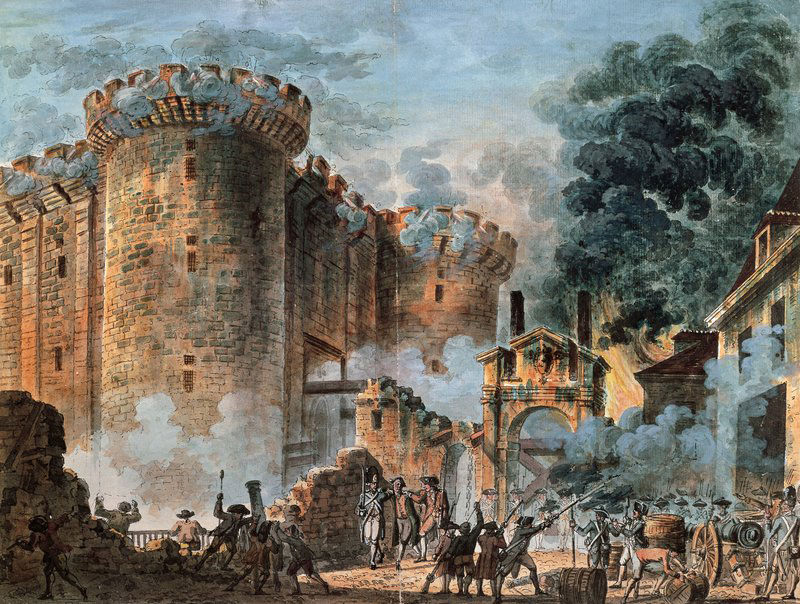

On the other hand, this weakness in communication is effective as a rhetorical game design strategy in order to clearly show the player which side they should be on throughout the narrative, and to ensure that there is no other acceptable option other than a revolution for freedom. The pro-rebel turning point of this revolution, probably in reference to the Storming of the Bastille prison in the French Revolution, is the storming of the prison Nova Prospekt, where Freeman's heroism, the Combine's greatest hidden horrors, and the subversive potential of the uprising are publicly demonstrated.

Left: The Storming of The Bastille represented in "Prise de la Bastille", by Jean-Pierre Houël; right: the storming of Nova Prospekt, the invasion of the prison Nova Prospekt by antlions tamed by rebel forces in Half-Life 2. Sources: Wiki Commons, Valve.

IV. Final thoughts

Through historical parallels and concepts of game theory, political philosophy and communication theory, we have seen in this essay the colonial power relations between humans and the Combine forces in Half-Life 2 and the game design choices around Dr. Breen's totalitarian mass communication. We have discovered how this game teaches, while respecting the player's freedom, different types and hierarchies of power and how it silently builds its pro-human and pro-rebel rhetoric through the weaknesses of Dr. Breen's strategies.

It should be noted that many aspects of Half-Life 2's narrative design have not been discussed, such as the role of the vortigaunts (key allies of the rebels), and the ambiguous and contractual role of the G-Man during Gordon Freeman's journey. Our analytical approach for this story reveals only part of what makes the game interesting even to this day; if you haven't played Half-Life 2 yet, you'll find mysteries in the plot and reflections of themes that go beyond the issues we chose to analyze.

Half-Life 2 is the leading example to date of an FPS with a quietly oppressive urban aesthetic and a persuasive, organic linear narrative design, which is a result not only of its gameplay innovations, but also of Viktor Antonov's visionary art direction and Marc Laidlaw's careful writing, as demonstrated throughout this story. Far from being a "mere" precious relic of the past, this dynamic and engaging video game narrative created in the early 2000s should remain among the most notable as far as the subjects of this story are concerned for a long time to come.