Chrono Trigger/Chrono Cross and Temporal Ontology, Part 2

Understanding existence and identity in the different time structures of Chrono Trigger and Chrono Cross

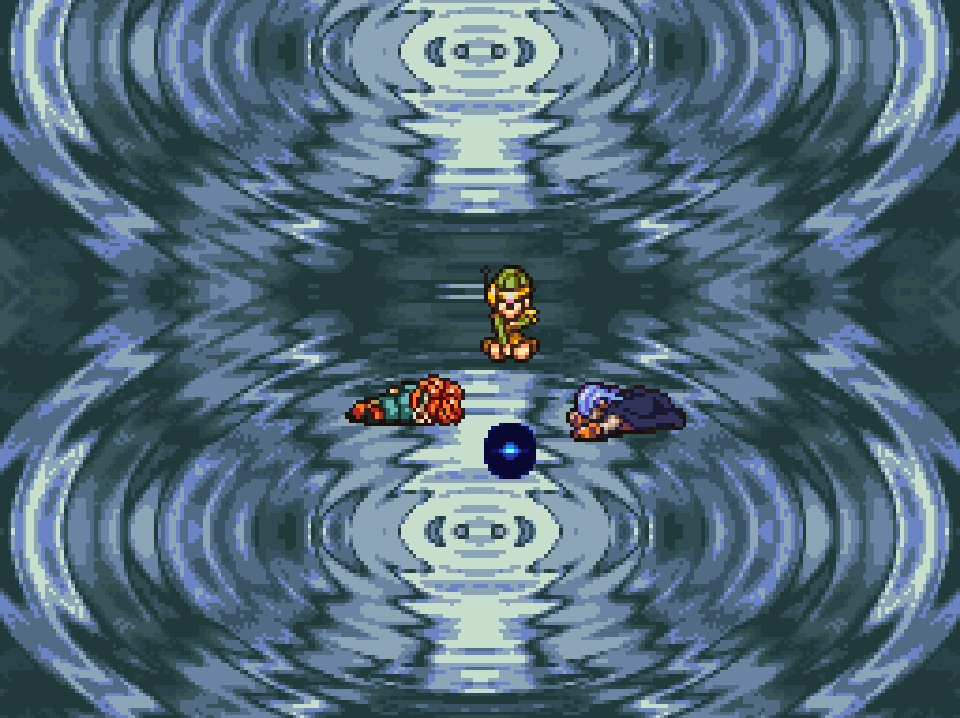

One of the most fascinating things about the Chrono series is its time travel, and today we are going to continue to elucidate some of the issues with this mechanic. As referenced in the title, this is Part 2 of the series, so don't forget to click the link below to read Part 1!

Now continuing the duology of articles on temporal ontology in the Chrono series, today we are going to talk about two fundamental concepts in ontology: existence and identity. More specifically, we will discuss these concepts considering the structure of time. What time structures? Those of the Chrono Trigger (linear) and Chrono Cross (multitemporal branched) temporal structures. These titles are very timely for debating these concepts because they pose interesting questions about identity and existence through different executions of the time travel premise.

Being that this is a continuation of Part 1, it is recommended that you have read it as I mentioned above. As they are different topics in the area of Ontology, however, it is possible to follow this article separately. To this end, I will revisit what we have seen in the theory applied to Chrono Trigger/Chrono Cross, and then, in the next topic, I will address the question of existence and identity in Trigger's temporality and, subsequently, in Cross's temporality.

In Part 1, it was said that Ontology is a subfield of Philosophy that studies existence as such and, more specifically, problems related to what something is, how to define its existence, and the consequences of that. For example, in the ontology of fiction, among other things, what is a fictional work, in what sense can we say that a fictional character exists, and what constitutes its existence? Similar questions arise, for example, if we ask “what is a number?” (as an abstract entity), and so on. In our case, we are interested in the Ontology of Time, which addresses questions such as “what is time?” and also more specific problems within a time frame.

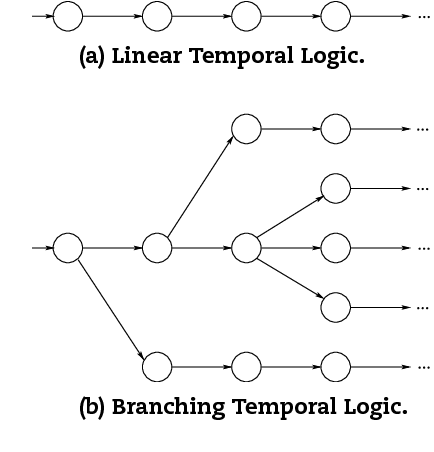

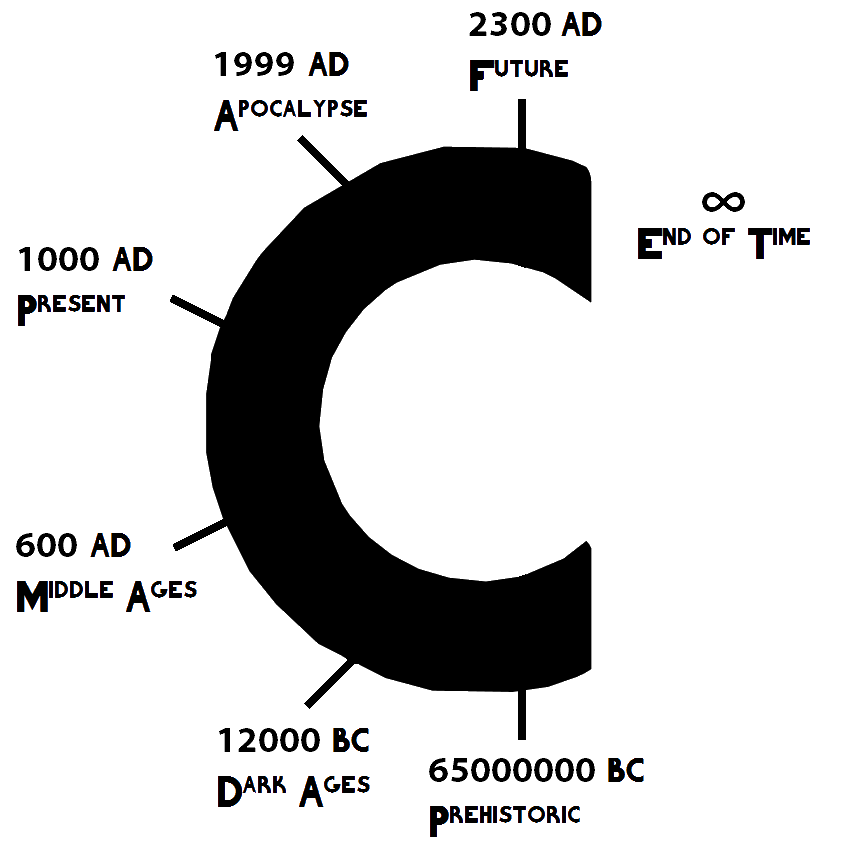

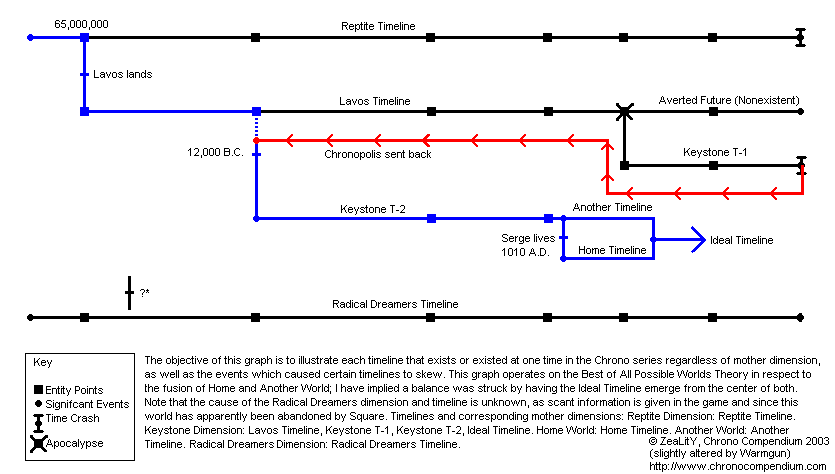

We saw that Chrono Trigger presupposes an ontology of linear time, that is, time is like a straight line with past-present-future. This means that, in a time travel, if Chrono and his friends manage to defeat Lavos in the past, the future in which he is not defeated and destroys much of life on the planet simply ceases to exist.

On the other hand, if it were a branching-time ontology, it would not be like this. There would be two possible futures, one branching from the point of time travel in which Lavos is defeated and the other would lead to a future in which he is not defeated. And it is in this logic that Chrono Cross works.

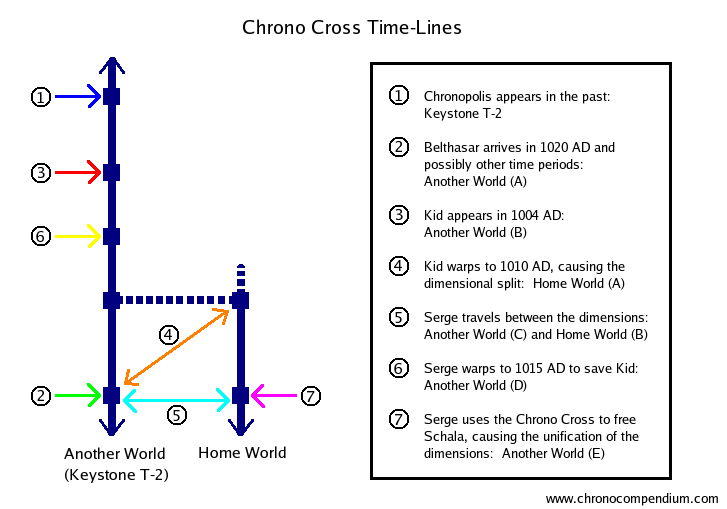

In the events of Cross, for example, there is a branch: in one timeline, Serge drowned as a child, and another in which Serge did not die and is controlled by the player 10 years into the future from that event that would have killed him. Note that from this perspective there is a point in common between these branches before Serge goes to sea (where he drowned and died or did not die). All the past is equal between these two timelines, but from that point on, no more, and the temporal changes are accumulating, being able, via chaos theory, to generate very different futures.

This issue of having a common point for branching is very important. Because one thing is a tree-branched time structure whose branches all have a common point at some level, a common past. Another thing is a branching web (or “multitemporal”) structure, where there are timelines that are completely parallel to each other, with nothing in common, except by analogy. For the Chrono series to be unified, it is necessary to assume a structure of this second type, branched into a web.

From here, we will call Chrono Trigger’s linear timeline “Trigger-time”, “Cross-time” for the set of ramified timelines of Chrono Cross, and “multitemporality” for the web-based temporal structure that encompasses Trigger, Cross, the VN Radical Dreamers, and any other parallel timelines (some branched, others not), including our real timeline (which is hinted at in the Chrono Cross credits).

Existence and identity in Trigger-time

Existence and identity are two very related concepts; there is no way to talk about one thing without talking about the other because demarcating what a being is, also means asking about what distinguishes it from others or what does not exist. But both concepts can be approached in a static way (outside of time) or inside time. For example, someone might ask: “Who is Robo?”, and an answer might be: “it is one of the robots created to be human assistants whose serial number is R-66Y”. Note that this answers what is the Robo (a robot) and its role (human assistant) identifies precisely which robot it is within this set (R-66Y).

The above answer grants an identity to the charismatic robot we put in our Chrono Trigger group. But it's a pretty weak identity, for what else is there to this robot that others don't have? By this answer, very little, as he is just another robot in a series of robots that happened to be numbered R-66Y. However, any Trigger player knows that he is much more than just a robot, because of everything unique that has been built in history with this character over time. And this is where “identity in time” comes in.

From a static point of view, Robo is just one more robot among many, nothing more, but from a temporal point of view, insofar as he shares links with other characters and he himself has a memory, we can say that he has a kind of "journey". This life journey defines Robo as something unique and distinct from the other robots in his series. Thus, we can say that Robo is the only one of his series that was found by Crono and his friends in Proto Dome in 2300 A.D., joined the group and went through all the adventures of the game; his story defines him as unique for him, for Crono and his friends and for the history of the fictional world in which he is inserted.

Note that, from this perspective, we can say that a robot is defined by what it is over time in two ways:

- (1) for its enduring characteristics (which last in time), such as the fact that it is a robot with the projected characteristics of one of its series;

- and (2) by his journey through time, that is, those things that have changed in him over time, but that are connected by his story, which is unique.

One could ask the following question: but then, considering that Robo has changed a lot along his journey, is he at the end of the game the same Robo that was found at the beginning of the game? From the point of view of (1), yes, as it retains the essence of being a robot with serial number R-66Y. From the point of view of (2), it depends: he is at different points in his journey, so he is significantly different, but considering that his essence is the same and there is a story that connects both (Robo at the beginning and Robo at the end of the game), so it's the same character.

Could this problem be posed to any human being, he as a baby and he at the end of his life, an elderly person, is he the same person? He has changed a lot, but, yes, for certain things that remain from the origin and for the history that unites what he was and what he came to be, the answer seems simple. Not so much, there are exceptions that lead to long debates in Philosophy. But as the idea is not to delve deeper, let's leave it as it is, the interesting thing is to show how everything changes when we consider a branching-time like that of Chrono Cross.

Existence and identity in Cross-time

In Chrono Cross, the consequences of time travel are much more complicated. A character may encounter an alternate version of him/her, in such a way that we can ask ourselves: “are they the same character?”. Considering the two criteria from the previous topic, we can say either yes, by criterion (1), or no, by criterion (2).

Consider the Cross-time bifurcation moment in 1010 A.D. At that moment, a timeline appeared where Serge is dead and another where Serge is still alive. Even though it seems like something small, over time, it has consequences for the world as a whole, by domino effect. Consider the case of Norris, a character who joins Serge and his friends' group and, traveling to that timeline where Serge is dead, finds himself "with himself", i.e. the Norris from that other timeline.

By criterion (1), both characters named Norris have things in common of origin, such as, for example, having the same name. On the other hand, by criterion (2), both have a different history in time and had different journeys, each in a different timeline. In these cases, where there are counterparts of an entity in parallel worlds, philosophers such as David Lewis argue that they cannot be said to be the same entity, since they do not share a cause-and-effect relationship.

Lewis is calling attention to the following: suppose Serge and his friends (including Norris), in this parallel timeline, kill the Norris of that time. What consequence would it have for Norris who is in the player's group? None. That wouldn't change anything about playable Norris or his world, because they're in parallel timelines, with independent futures.

Note that this reasoning doesn't work in Trigger-time. If Crono and his friends (including Robo) traveled to the future, and if they found Robo there before joining the group (which is not possible in-game), that Robo if destroyed, would make the party's Robo disappear as well. Because Trigger-time is linear time, it makes no sense for the Robo to be in your party if, in the past, it was destroyed before it could enter the party.

Note that this generates a temporal paradox (similar to what we mentioned in Part 1). This paradox arises precisely because they are the same entity, on the same timeline, and share cause and effect relationships. So, we can say, then, that the two Norris of Cross (as well as the other parallel versions of characters in the game) are not exactly the same character, at least not in the sense of “same character” that we use when talking about the characters of Trigger.

Existence and identity in Multitemporality

Finally, we need to talk about existence and identity in multitemporality. In the credits of one of the endings of Chrono Cross, we see footage of a real girl who looks like Kid who is looking for someone in our real world. According to director and writer Masato Kato, that someone would be the player himself. Because of this allusion, and also because there are similar characters with the same name in the Chrono series games, to what extent can we say that they are the same character?

We know, for example, three versions of Kid, one in Cross, one in VN Radical Dreamers, and another supposedly in the real-life timeline (for the credits). It is likely from Chrono's lore that there are numerous versions of the Kid. What makes all these characters the same? By criterion (2), they are not the same, they all have totally different journeys of life in independent times.

By criterion (1), also some versions of Kid are not the same character, since they can even change in essence and questions of origin. The timeline of Radical Dreamers, for example, is not an offshoot of Cross-time, it's a time parallel to that, and ditto for the real-world Kid. One way, then, of characterizing an identity in a weak sense for these cases is what philosophers like Tomasz Placek (2012) call “Many-Worlds Interpretation”.

Many-Worlds Interpretation is that established by entities from different worlds and/or times, but which have their potential in common. For example, you can do many things with a block of wood, like turning it into a table or a chair, but you cannot turn it into an iron tank. The potentialities of wood are restricted, in a possible world/time, it may have turned into a table, in another, a chair, but there are limitations to what it can be.

In this sense, we can say that the concept of existence can be understood in a Many-Worlds or multitemporal way, even if the objects have distinct identities. The consequences of this are quite interesting, and one of them is that the concept of existence transcends that of identity: someone can die, lose their identification in the world, but their existence, in a sense, continues. For example: Serge died in one of the branches of Cross-time, but he didn't cease to exist, because there are other versions of Serge, like the one playable in Chrono Cross and the one playable in Radical Dreamers.

So, how are the neurons doing? I know some of these concepts are mind-blowing, don't you? The Chrono series is very interesting in its world construction. I hope you enjoyed this article and also the article in Part 1, and feel free to comment on questions, objections, interpretations of the lore of these games, etc.

If you want to delve into some of these topics, in addition to the Lewis and Placek hyperlinks, I also recommend an entry on identity in the Stanford encyclopedia and the aforementioned three books in Part 1 that are very good for an overview of these topics in Philosophy and Logic: The Logic of Time, by van Benthem; and Stanford entries Time and Temporal Parts. For more information on the Chrono series chronology, I also recommend Chrono Compendium.

This text was originally published in Nintendo Blast (Portuguese).