Celebrating David Szymanski's Small Wonders

Bite-sized Szymanski snacks

David Szymanski needs no introduction, but I will give him one anyway. He is the developer and brain-father behind one of the best first-person shooters on the market (Dusk), the game that is credited with single-handedly revitalizing the boomer-shooter genre.

David Szymanski is not just a skilled programmer and game developer: he has a knack for creating unique horror aesthetics, calling back to the early 3D models from games of yore, as well as showcasing particular expertise in level design. Dusk's levels are surreal horror treats, with interesting layouts and roundabout topsy-turvy connections and shortcuts.

The shooting in Dusk is superb: the guns feel hefty and powerful when shot, aided by brilliant sound design. There are all these tiny flairs I just adore: you can execute back/front flips with dual-wielding shotguns for some MLG-style kills, the environments have interactivity up the wazoo and you can spin your pistols Revolver Ocelot-style with the push of a single button.

I love Dusk, and you should too. This article is not about Dusk, however. Instead, I want to celebrate David Szymanski's smaller projects. This retrospective will ignore his pre-Dusk output (SUPERJUMP is a cynicism-free gaming magazine and I, unfortunately, have very few kind words I can share about Moon Silver, Fingerbones, The Music Machine, and A Wolf in Autumn). These are his less stellar, more amateurish works. I will also not mention Gloomwood or Butcher's Creek, the former because of its larger scope and current state as an early access game, and the latter as it has yet to be released (at the time of writing).

While smaller in scale, the following games contain the same soul as Dusk: the love of experimenting with game design, the joys of shlocky, B-movie-style horror, and the ability to deconstruct and renew cemented game genres.

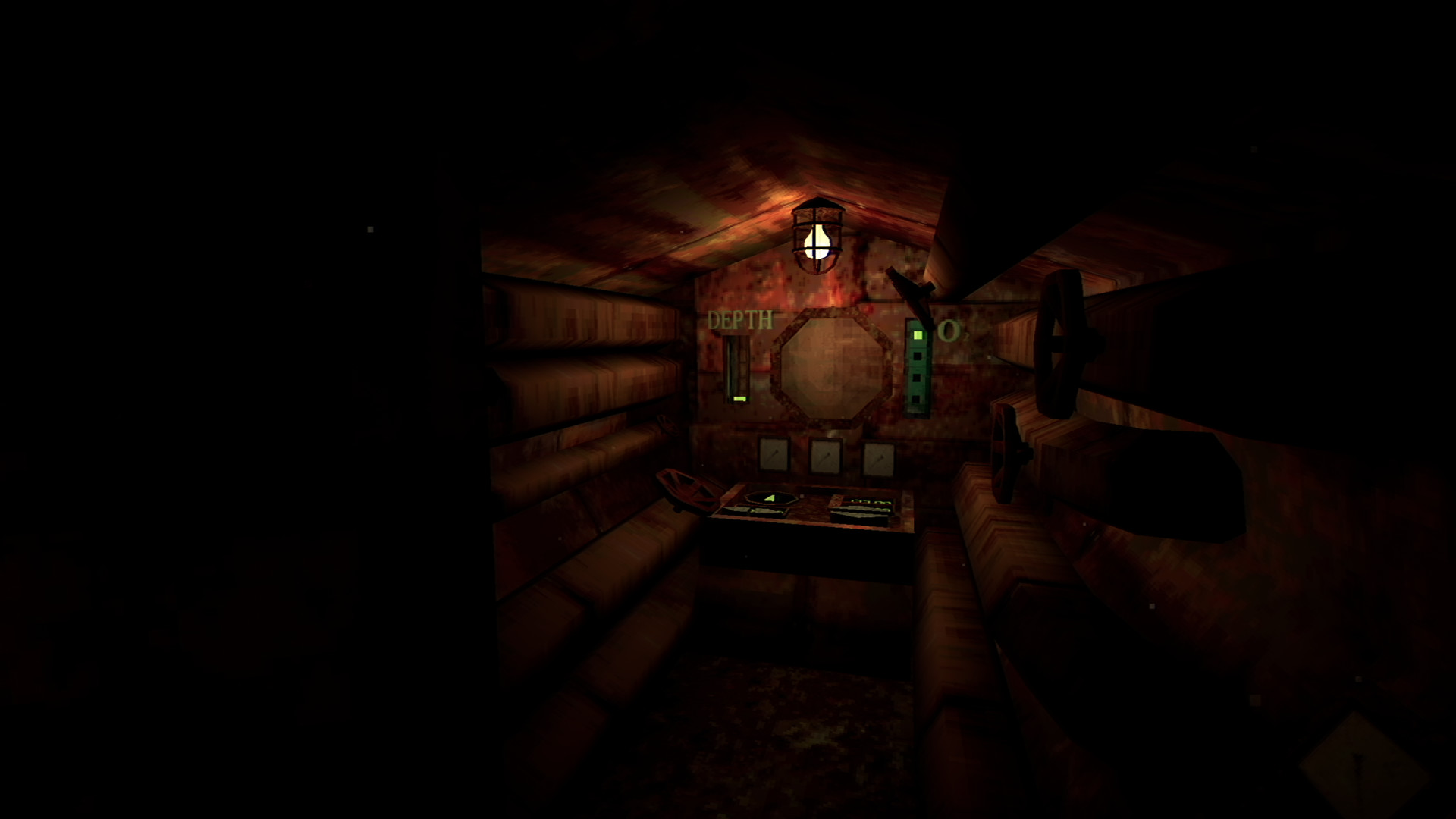

Claustrophobic Horror: Stuck Inside the Iron Lung

The sanguine sea roars. All livable planets dissipated in a silent rapture. Below crushing depths, in a makeshift submarine, you play as a convicted felon attempting to earn their freedom. You are promised release from shackles if you explore an anomaly – a moon with a blood ocean. You were doomed from the start. This iron can wasn't made to withstand these depths. Oxygen levels are running low. You hear pounding on the walls of the vessel. The radar beeps an incessant noise. You are not alone. This moon might be alive, or something else hides in its innards.

Outside of Dusk, Iron Lung might be Szymanski's most popular work. It's heavily coveted by the incessant crowd of screaming Spooktubers. The Jacksepticeye-types play horror games and scream as loud as they can when a monster pops out going "A boogly-woogly-boo!". Markiplier himself is aiding in the making of an Iron Lung movie. Don't let the fanbase fool you: Iron Lung is an amazing horror experience. More than outright scares, it's incredible in its ability to build tension.

The game is a slow boil. There's already something quite uncanny and nerve-wracking about being submerged in a tin can beneath an ocean of blood. It's one of the most horrifying scenarios I can imagine, to be honest. The gameplay loop is rather simple. The goal is to take pictures of various locations of interest, as things start going horribly wrong with your metal bin of a sub. The portholes and windows are welded shut. You are blind as a gopher. To navigate and traverse the blood ocean, you press directional buttons on a rusted dashboard, and use a combination of a sonic radar, map, and X and Y coordinates to figure out where the heck you are.

There's an oxygen meter that is purely artificial – it doesn't actually decrease over time, but its levels lower as you progress and take the necessary snapshots. First-time players probably don't know that, fomenting a certain time anxiety, which promotes madder dashes and scrambled, anxious thoughts.

![[bf]David Szymanski's Leftovers](https://www.superjumpmagazine.com/content/images/size/w2000/2024/06/david-1.jpg)

The pictures you snap with a big console in the back play out in a rising crescendo, from mysterious sunken rigs to skeletal corpses; then, suddenly, the camera spots a mysterious creature, blurred by motion. After a couple more pics, an eye stares back at you from the screen.

The build-up until the final (and only) jump-scare is what makes the game a masterclass of horror, even with the fact the low-poly worm-like creature isn't actually that scary to stare at.

Iron Lung is short, it's sweet, and I can definitely recommend it as a midnight snack with the lights turned off.

Chop, Chop, Chop 'Em Up! Chop Goblins!

Have you ever been so annoyed at those screeching critters from the Gremlins movies that you wished you could gun 'em down with a Tommy gun? Well, you're in luck – Chop Goblins is the perfect game for you!

While Dusk is a vast and roundabout FPS, Chop Goblins is a time-hopping "micro-shooter" with an arcadey flair. It's a machine that extracts the maximum amount of joy from shootin' and stabbin' grinny, teethy gobbos.

Chop Goblins is made to be played in a single sitting, to amass as many points as possible via coin collecting, precise headshots, and multi-kills. Levels are short and delicious, continuing Dusk's tradition of interesting connections and loop-like level design.

While Dusk retains a consistent horror aesthetic, Chop Goblins adds some time traveling to the mix, switching it up with interesting locales and a whole lot of corny humor. The game gave me a hearty chuckle in the second level, set in a city, when a building collapses – the flavor text implying those darn goblins "chopped the building up". Soon after, you will be in Dracula's castle hunting the eponymous bloodsucker, then an ancient Greek temple blasting the gobs with magic lightning and you'll even explore a doomed future where the Goblins have chop-chopped their way to world domination.

Chop Goblins is like eating a big bowl of overly sweet cereal for dinner: it's not the healthiest or most mature meal, but it is oh-so-good in the moment.

Squirrel Stapler: God is Coming

The rotting corpse of your lover is starting to stink. Its luster is gone. It's swarming with flies. To recover its beauty you set out to staple squirrels on the headless cadaver. The problem is that God does not allow this. It is the gravest of sins. God is coming in 5 days, and he is not happy.

Squirrel Stapler plays like a Cabela's arcade hunting game if it endured a particularly bad acid trip in the forest – one in which it committed manslaughter and saw the face of divinity on the waving trees. It's absurdist daytime horror at its finest. It plays with the fear of an encroaching presence that is all the more apparent and engrossing as time passes.

It's very opposite to other Szymanski works, with its creeping pace and methodological hunting gameplay. Making too much noise alerts your quarry – you must stay low, stalk your prey, and track its trail. You are the hunter of squirrels before you yourself become hunted by divinity. Each day, more and more threats appear, adding to your own feelings of vulnerability as the number of squirrels you need to kill and staple each day also increases.

Its blocky, pixelated environments grant me the impression of being an infinitesimally small human amidst a vast nature reserve. The map is huge, and your prey is small. You are subjected to all these role reversals that are oh-so interesting – you are the hunter becoming the hunted, the big becoming minute, someone who thinks of themselves as undertaking the holiest and most beautiful of tasks, but instead committing the most brutal of sins.

As I staple beautiful squirrels to my lover, I feel the eyes of God staring unto my neck. His warriors harass and harangue me. God arrives tomorrow, and I must scream.

Squirrel Stapler is a meal that is best served raw, and the chef insists that's the way it's meant to be eaten. When you actually dare to eat the tartare, it is delicious, but it might make you sick down the line.

Off to Work at The Pony Factory

The Pony Factory reminds me of those bloodstained notes and journals you run into in survival horror games a la Resident Evil. Those words scribbled by a mad scientist that read something akin to:

04/20/1969

I have injected this ferocious mutt with a virus that multiplies its speed and strength. I've also replaced all of its limbs with chainsaws. I am prodding it with a taser every 30 minutes to test its aggression levels.

04/21/1969

It escaped...

What did you think was going to happen when the ruling capitalist class corrupted the "Friendship is Magic" forces of (my) little ponies? Well, now you get your answer – a man is forced into a slow stumble through darkened hallways armed with nothing but a nail gun, only to be assaulted by horrifically morphed bipedal equestrians.

The Pony Factory is yet another first-person shooter that plays like an antithesis to the boomer shooter genre. Gone is the banshee-like speed of Dusk, replaced by a snail's pace – a slow crawl through an abandoned, monochromatic factory.

The objective of each short level is to find the one open door that takes you to the next section. On the way, you will encounter monstrous ponies that you must gun down with your trusty nail gun, your only weapon. In between these firefights, you must scramble to find ammo, medkits, upgrades for your gun, and every now and then a note that expands on the game's story – and reads like the worst Umbrella Corp scientists concocting the cruelest of experiments.

The game's shining success is how it plays with dark and light. The Pony Factory uses lighting and color to set the mood and diversify the gameplay. It is a rather intense game – the lack of overt light sources obfuscates the screeching malformed pony-monsters, hiding in the darkness.

You can't equip your only light source, a flashlight, at the same time as your full-auto gun. The player must always make a choice between visibility and self-defense. The main challenge of the game is the combination of the slow speed, the obscurity of your surroundings, and having to frenetically switch to your gun after shining a light on a creepy creature in the corner, while ensuring you have enough space to riddle it with nails before they maul you to death.

There are two quite shocking revelations in the late game. First, you as the player character are responsible for all the horrible stuff that happened in the horsey factory. Second, the game does indeed have color. This is obvious if you're paying attention, as the monsters' blood splatter is not greyscale, but a dark crimson. The game doesn't just darken everything by slapping a black-and-white filter over the whole shebang – the whole world is devoid of color due to the pony-magic-harnessing shenanigans. The later levels contain hues of blue, red, and green, which really hammers home how much the world has been corrupted and how grand your cock-up was. The outside world is equally grey and dreary as the inside of the factory, and it's all your fault.

Pony Factory is a surprisingly delicious grey sludge soup that serves as a warming meal for a dreary day. I definitely recommend playing this game on an overcast, grey-clouds kind of day.

If Dusk is a full-course meal, these smaller projects are akin to bite-sized snacks: short games that are sometimes sweet, sometimes sour, but always some form of experimental amuse-bouche with mouthwatering flavor.

For these short games, David Szymanski takes known conventions and subverts them. It's an excellent design ethos to abide by – make short, 1-2 hour games, that play with genres and horror aesthetics. Through the development of brief games, designers can learn and improve their coding chops. It can show them how to overcome the myriad of challenges that come with making a game. Because making a game – any game – is laborious and complicated.

Above all, it reinforces an opinion I've always held strongly – that a game doesn't have to be endlessly re-playable and stuffed with content to be a great experience. These games made me chuckle, terrified me to my core, and even led me to philosophize about game design. My emotional experience of these games was just as grandiose as my playthroughs of, say, Elden Ring and Baldur's Gate 3. In the age of hundred-hour-epics, David Szymanski's work remains vibrant, fresh, and exciting. I look forward to playing more of his games – big or small – and getting some more of that juicy, low-poly greatness.