Celebrating 25 Years of PlayStation

The SUPERJUMP team reflect on their personal histories with Sony’s iconic game consoles

Twenty five years is almost an eternity in the video games. In some respects, it still feels like a very young industry, and one that is continually pushing at the boundaries as it grows into adulthood — artistically, technologically, and even conceptually (the very definition of “video game” is debatable in some quarters today, depending on the title you’re referring to).

As gamers, we each have deep personal experiences with this medium. Like an increasing number of people around the world, I grew up with video games. Next year, I’ll be 37 years old; this is notable because when I discuss games with others — especially the lovely folks who write for Super Jump — I am immediately reminded that the era in which we grow up greatly informs our overall view of the major players. For example, there’s a part of me that still sees Sony and the PlayStation as a relatively new presence in the industry. It’s rather remarkable, then, to be sitting here, writing an article about PlayStation’s 25 years on the scene. I grew up with Nintendo and Sega as the major pillars of video games — to me, they almost feel like the mother and father of the industry. I recognise, though, that there’s a generation older than me (if you can believe it!) who feel this way about Atari rather than Nintendo or Sega. So it makes sense, in turn, that millions of gamers grew up viewing PlayStation in this way.

The original PlayStation console was released in Japan in 1994, and in other major territories in 1995. Building a video game console is always an enormous challenge, especially so in the context within which the first PlayStation was born. Sony had famously tried to enter the industry by partnering with an established player (they signed a contract with Nintendo to produce a CD-ROM add-on for the wildly-popular Super Nintendo Entertainment System). We know, of course, that the fabled add-on never launched and that Sony ultimately decided to go their own way and develop their own console. What you may not know is that birthing the first PlayStation was no easy feat — not just because of the enormous technical challenges associated with building a powerful, cutting-edge console capable of producing sophisticated 3D graphics — but also, crucially, because the project had to be navigated through the political minefield of an enormous electronics company; a company that was being asked to dive into an established market against two highly-entrenched companies that each had widely-recognised and beloved game franchises of their own.

Source: Unsplash.

Although many people worked on the PlayStation project, the credit ultimately — and appropriately — goes to Ken Kutaragi, the man often dubbed “father of the PlayStation”. It was Kutaragi who personally convinced Sony’s then-CEO, Norio Ohga, that the company needed to be a player in the game industry. Kutaragi was a remarkably unique individual; his general approach was regularly at odds with traditional Japanese corporate culture. He was famous (or infamous) for his raging temper, his tendency to micromanage staff, and his dogged pursuit of his vision. The people who worked with Kutaragi, including senior Sony executives, would later compare him with Steve Jobs. Some former Sony staff claim that Kutaragi was more like a combination of Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, in the sense that he harboured ambitious vision for the PlayStation, but he also had a deep understanding of the technology itself. Although Kutaragi ultimately left Sony as a result of the botched PlayStation 3 launch, he is undoubtedly the key catalyst behind the entire PlayStation venture to begin with.

Standing here now, in 2019, 25 years after the original PlayStation launched, the impact of the iconic gaming platform is obvious. If we take the top five highest-selling consoles of all time, we find that PlayStation consoles hold three of the top five spaces. The PlayStation 2 is still the highest-selling console in history, with around 159 million units sold. PlayStation 4 comes in at number three with 102.8 million sold (so far), and the original PlayStation sits at around 102.4 million.

The staggering success of the PlayStation brand can be attributed to many things — certainly, Sony is often rightly credited with truly making video games mainstream, largely through their innovative and bold approach to marketing over the years — but really, any video game console is only as good as its games. Over the decades, Sony got two major things right: it established its own legendary exclusive franchises, and it encouraged some of the world’s greatest developers to build games (often exclusives) for its consoles. Sony managed to peel massive companies (like Square Enix) away from their traditional homes and convince them to bring their most beloved franchises to PlayStation — often in bold, ambitious new forms.

Any attempt to celebrate the last 25 years of PlayStation — a series of consoles that has given rise to thousands of incredible games — is never going to be comprehensive enough to truly capture the impact of the brand. So, when thinking about how to approach this, I kept it simple. I asked the Super Jump team to consider their own personal histories with PlayStation. From there, each of us chose three PlayStation games that had a major impact on our lives as gamers. Why only three? Well, I’m sure we could all have listed dozens upon dozens — but in the end, editing down our choices to only three ensures that we really think carefully about those games that genuinely mean the most to us.

So, let’s get into our stories. I hope you’ll enjoy reading these as much as we enjoyed writing them.

July 1997. That’s when it all began. I was surprised with a PlayStation, Formula 1, Pandemonium, and a demo disc. If the Mega Drive and Sonic the Hedgehog 3began my journey into games in 1994, this era was how games could show me the possibilities of where they were heading, and where the crossroads of games and movies were starting to blur.

Metal Gear Solid

PlayStation (1998)

When thinking about my three games, this spot came down to either Metal Gear Solid or Tomb Raider 2. So, why Metal Gear?

It first introduced the notion that ‘story’ could play a big part in the game. You could sit back on occasion and be immersed in what was going on in the world of Solid Snake. The story involved playing as Snake himself, an agent brought out of retirement to stop a group of mercenaries, who have taken over a military facility in Alaska, with the leader calling himself ‘Liquid Snake’. The mission is to infiltrate the base, and to stop the group and their ransom demands by any means necessary, although the plot isn’t quite as simple as that.

I first came across the game through a demo disc. It stuck out because OPM (Official PlayStation Magazine) had a special issue dedicated to the game, and so was the disk attached. I must have played through the small section of the game, which ended at the DARPA Chief, hundreds of times. Because it had the area of the snowfield with the helipad in this demo, it was tempting to see how enemies would react to certain weapons being used, whether if it was with a chaff grenade, or fists.

The real moment came when you would be running through the snow, and those words would be heard:

‘Whose footprints are these?’

It blew my mind in two ways: there were footprints in the snow made by me, and the soldier was following the trail I had made. There wasn’t a set path, there was no confusion, it just seemed natural.

Games of the era still had linearity, but here it bent that rule: you could knock out a guard across a room if you wanted to, or kill another with the SOCOM, or just avoid them completely. There was a new option here which was never there before; choice.

Again, the story is incredible, as it makes you ‘care’ for certain characters, even if they’re just a portrait on the codec screen. I must have completed the game 30 times in the last twenty years, but the arc of Ninja is one that I can never get used to. I still hope that I can change the outcome.

You couple that with the incredible story, the bosses, the environments, and the little touches scattered across the game, and you have an epic, outstanding, enthralling interactive game that still stands up today.

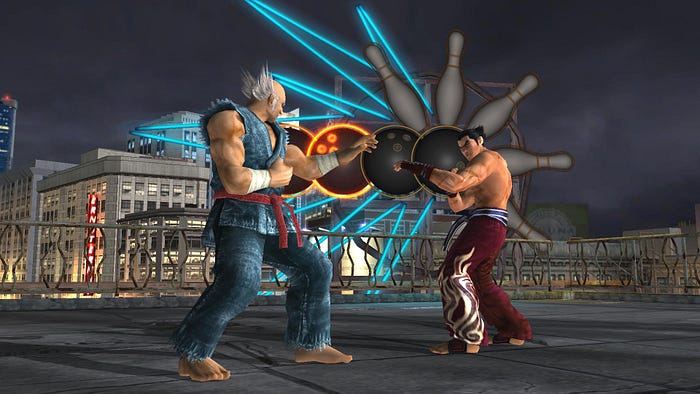

Tekken 5

PlayStation 2 (2004)

One can’t talk about just a single Tekken game in an article. In order to understand why I’ve picked the fifth instalment, I’ve got to cover some history.

Tekken is a series that has been a staple of PlayStation. The first game launched just a couple of months after the console itself debuted, but it’s still erroneously regarded as a launch title.

Tekken 2 was the game I first came across in the series. Again, it was from a demo disc, of which had no music, and only had ‘Jun’ or ‘Lei’ has playable characters. But after coming from a previous generation of Street Fighter II and Rise of the Robots, seeing the close-ups of throws and combos at different angles were incredible to see. There were fully-3D polygonal graphics that changed how I saw how fighting games could work.

Tekken 3 only raised the bar of this, especially with ‘Tekken Force’ and ‘Tekken Ball’ mode to continue the unpredictability of the series, especially with a kangaroo as a playable character in the previous game.

Tekken 4 was a strange entry, as it seemed to be developed by a different team. The music and graphical style seemed like a departure of what made Tekken, Tekken. But the gameplay was still intact.

When it came to Tekken 5, it was the tenth anniversary of the franchise, and it seemed as though that Namco had learnt the lessons of the fourth instalment. Gone were the uneven levels, and the stages were now fully flat, even-ing the matches, but the walls remained, keeping the pressure of that moment when you have nowhere to go, and your character is being pummelled by JACK-5.

There were 32 playable characters this time (double what Tekken 4 offered). An incredible amount of variety had now returned, not seen since Tekken Tag Tournament, and favourites such as JACK and Armor King returned. I loved the amount of characters to play here, and each one had their own challenges in mastering their combos and special moves.

Instead of a ‘Tekken Force’ mode, there was ‘Devil Within’, a mini-game where you controlled Jin, and it was almost a 3D Streets of Rage experience. After completing it, you would unlock another character.

But this was only the start of the content. Incredibly, it offered arcade-perfect ports of Tekken 1, 2 and 3 here. All were available from the start, which only extended the replayability tenfold. It’s a game I repeatedly come back to. It’s the compilation of everything that works in a Tekken game, and then some. It has fantastic music again, and the graphics, even fifteen years later, hold up well.

It’s a shame that there hasn’t been an HD remaster of Tekn 5, but hopefully, there might be something on the horizon with PlayStation 5.

Demo Discs

Early PlayStation

Powerline. If you used a demo disc during the original PlayStation days, you’ve already got the image of the logo in your mind, alongside the music that would play when choosing a game.

Powerline demo disc. Source: YouTube.

Demo discs were a huge part of my experience with the first PlayStation console. In a time before we had internet and I was only catching up on new games with my GamesMaster magazine subscription, paying £4.99 for a magazine and a disc would straight away bring me access to a taste of the latest game at that current time. I remember playing a timed-demo of Resident Evil 2 (it included ten minutes from the start of the game; I would see just how far I could get in that time). Another example was Tomb Raider 3. Due to the time difference between publishing a demo on a disc and publishing the final build of the game, stages that appeared in demos could be in quite different states to the end result. The ‘Area 51’ level here was in a much earlier state, alongside certain of Lara’s animations.

Another aspect to the demos were the so-called Net Yaroze games. These were the nineties version of ‘indie’ games, before indie was recognised as a large part of the gaming community. You could play RPGs such as Terra Incognita, or a simple platformer with time-travel elements called Time Slip. For what you paid, it was incredible value, and only made you think as to what was coming in the following month. The other hope was to see what titles were ‘game’ or ‘video’. I remember hoping to see Dino Crisis marked as ‘playable’, and eventually I did.

I was introduced to so many games here, that I simply do not know how else I could have understood what types of games worked for me and what didn’t. It’s one thing to read about one, but it’s a totally different experience when playing an excerpt from it, even if it’s an early version.

It was a massive part of the PlayStation experience, and I believe it was also why the console was such a big success. It would have been impossible for a Nintendo 64 cart full of demos to appear every month. Granted, there was a demo disc series for the Sega Saturn; but that was a console with a relatively short lifespan and demo discs certainly weren’t going to save it.

I still have my collection of demo discs in my gaming room. I still find it incredibly interesting to just load one up and see how a random game can play in 2019.

There are trials and free-to-play games, but I still miss the concept of a ‘demo’. They’re now ‘access the beta when pre-ordering’, and I find that a shame; though perhaps it’s just a necessary evil for a medium that has grown to become so ubiquitous.

As I mentioned in the opening paragraphs of this article, I’m now in my late 30s. My age definitely influences the way I view the PlayStation. I had grown up with the NES as my first game console, and my family was definitely a “Nintendo household” for the most part. I was exposed to Sega consoles primarily through school friends; I’d often visit a mate who lived just near my school to play his Master System and Mega Drive. I remember being especially impressed with Michael Jackson’s Moonwalker — it was just so different than anything I had experienced on a Nintendo machine. Games like Sonic the Hedgehog and Road Rash ultimately convinced me to beg my parents for a Sega console and eventually, they purchased a Mega Drive II, which I adored.

Both Sony’s PlayStation and Sega’s Saturn arrived when I had just started high school. I remember being intrigued by both, although it was the PlayStation that really caught my attention — in part, I think, because it felt so novel at the time. I’d been used to Nintendo and Sega consoles all my life, so it felt odd to see this sleek, flat, rectangular machine (produced by a non-gaming company) so prominently displayed at my favourite game stores.

Throughout 1995 and 1996, my only hands-on experience with the PlayStation came from a couple of friends who owned it. A big group of us used to have regular sleepovers, where we’d sit up and play the PlayStation all night long on a weekend — usually only stopping for breakfast before diving back in. These sleepovers are some of my favourite high school memories.

We didn’t have a PlayStation in our house until 1997, when my sister got one for Christmas. She got the console and a copy of Crash Bandicoot. I got a shiny new copy of Final Fantasy VII. Really, the rest is history: I’ve owned every single PlayStation home console since then.

It was incredibly difficult to choose the three PlayStation games that mean the most to me, but after doing some major soul-searching, here they are.

Bloodborne

PlayStation 4 (2015)

When thinking about these three games, I somehow expected to focus almost entirely on the original PlayStation console. Nostalgia, after all, is a powerful force, and I tend to feel that games just don’t have the ability to exert life-changing influence on people as they get older.

And yet, I kept coming back to Bloodborne. I have never really written a long article about this game, in part because I’m actually a little scared of not doing it justice. I know that must sound silly; and it’s ironic that my love for the game is the thing that keeps me from writing about it. Fundamentally, I find it difficult to put into words just how and why this masterpiece is as great as it is.

As video games go, Bloodborne is about as close as I’ve ever seen to a flawless game experience.

Its art design is almost unmatched, in my view. Yharnam’s gothic spires pierce a morose red sky and eventually give way to the distressed hovels of Hemwick Charnel Lane and the foggy depths beyond. After exploring Yharnam and its surrounds, you’ll eventually make your way to the mysterious Upper Cathedral Ward — by this time, darkness has fallen and the city is shrouded in a terrifying silence, broken only by the sound of your footsteps on the cobblestone. Your adventure is accompanied by a mournful-yet-dignified soundtrack that always strikes the appropriate tone. The gameplay — especially the fast-paced combat combined with the innovative regain system — is fluid and responsive; it relies on lightning-fast reflexes and a strategic, cerebral approach to enemy encounters.

And then there’s the story. Sure, there have been games with more technical sophistication when it comes to elements like facial animation, for example. But I’ve yet to see a game — any game — top the characters and story of Bloodborne.

For all the discussion and debate around great female characters, I’ve yet to see a video game heroine that comes close to Eileen the Crow — a middle-aged Hunter whose mere tone of voice (brilliantly played by Jacqueline Boatswain) betrays both tiredness and fierce determination. She speaks slowly, almost wearily, as if long past due for retirement. Her voice carries an undertone of softness — almost a motherly quality, at times — but is then punctuated by moments of slower, deeper, more deliberate emphasis on certain words. These moments send a shiver down the spine; they are the low growl of an experienced lioness. Calm, dignified, knowledgeable, and extremely dangerous. Eileen is one of manyexceptional characters in Bloodborne.

I can feel myself circling the event horizon here, trying not to fall into the endless black hole of Bloodborne lore and mythology: there’s just so much to say about this exceptional work of art. It’s an experience that continually surprises the player in the most delightful ways; even the fact that it starts out as beautifully-produced gothic horror and then veers wildly and expertly into an elaborate Lovecraftian nightmare. Just as you think you have come to grips with it, Bloodborne violently writhes out of your grasp and leads you down endless, interconnected rabbit holes.

The icing on the cake — and a key reason why Bloodborne is one of my top three PlayStation games ever — is that you can play cooperatively online. I’ve now been through both the main game and The Old Hunters expansion about three times with my sister. Those hours playing Bloodborne together have been among the very best of my life — we strategised every encounter as a team, we poured over the lore and discussed it in between sessions, and we occasionally even became virtual tourists in Yharnam itself, pointing out and discussing the many intricate details within the environment around us as we played.

Bloodborne is a masterpiece in its own right, and in my view, it’s a game everygamer should play. That I was able to share it with a family member makes it even more memorable.

Final Fantasy VII

PlayStation (1997)

I feel that the first game you own on any console is always going to be inherently very memorable. And although I’d played several PlayStation games prior to owning Final Fantasy VII, this was the first game I ever actually owned for the console.

Everything about the Final Fantasy VII experience was special. It was really the first JRPG to garner mainstream support in Western markets, which is itself no small feat. The launch was supported by an elaborate ad campaign here in Australia — and around the world — which focused heavily on Final Fantasy VII’sthen-revolutionary full motion video (FMV) sequences. The liberal use of FMV genuinely was revolutionary at the time. There were certainly many earlier games that had utilised the technique, but Final Fantasy VII was different. Not only were its FMV sequences highly advanced in terms of the animation quality itself, but the game featured hours of animated content sprinkled throughout — it was ambitious in scope and vision. It’s no surprise that Final Fantasy VIIbecame something of a poster child for not only the PlayStation, but for “next-gen gaming” as a whole. This game came on a whopping three CDs. It was a magnum opus, and really, we’d never seen anything like it in video games before. To some extent, I think Final Fantasy VII was the first game to genuinely realise the promise of “multimedia” from the early ‘90s — it was an experience that aimed (and largely succeeded) to merge video games and film into something greater.

So, this was not only my first PlayStation game, but it was my first turn-based RPG. Everything about it felt completely new to me. Come to think of it, I can’t actually say that I’d really played any game with such extensive emphasis on characters and story up to that point. So, part of the reason that Final Fantasy VIIis so memorable — and why it occupies a coveted space on my list — is because it actually delivered on the promise. It truly was ambitious; it felt like I was going on a massive, sprawling adventure that might never end. From memory, it took me nearly 50 hours to beat — I’ve never in my life played a game that required so much time to reach the credits.

And although I loved nearly every minute of Final Fantasy VII, I’ll never forget that intro sequence. The hovering shot above a steam-and-neon-bathed Midgar intercut with the urgent rushing of the train; being dropped straight into a high-stakes plot against the all-powerful Shinra Corporation in the middle of the night, with the ever-present danger of being caught and arrested…I mean, does it get much better, as far as openings go? I don’t think so. This was right up there for me alongside A Link to the Past in terms of best game intros in history.

Final Fantasy VII has perhaps become a victim of its own success in more recent years. It wasn’t a perfect game by any means, but I think there’s a tendency now to suggest that it “wasn’t actually as good as we thought it was at the time” or that somehow the flashy FMV blinded us all in the late ’90s. I don’t buy any of that. Final Fantasy VII has aged like any other game, of course. But I will never forget my first playthrough — it was pure magic. This is a game that well and truly earned its praise, and continues to rightfully occupy a special place in many gamers’ hearts.

Resident Evil

PlayStation (1996)

Remember those sleepovers I mentioned earlier? One thing I neglected to say was that these were almost entirely dedicated to the Resident Evil games. One of my PlayStation-owning mates had picked up the original Resident Evil and started playing it on one of these sleepovers — I think he had intended to play a few minutes and then move on to something else. Instead, he ended up starting after dinner and finishing when the sun came up the next day. We all sat around in the dark — in almost complete silence — watching him play. As the hours went by, we became deeply engrossed in the experience; some of us took notes to help solve puzzles, while others began chattering with anticipation about what could be behind the next door. Although one person was holding the controller, these nights were very much a shared experience — we felt like a group of survivors, trapped in the Spencer Mansion in the middle of nowhere. The group environment established a kind of Dutch courage that enabled us to venture ever deeper into the mansion.

I never actually owned the original Resident Evil. And yet, it was absolutely one of the most influential PlayStation games in my life; I’ll never be able to de-couple it from those fond memories from high school.

Over the years, I did end up playing the second and third Resident Evil games with that same friend who guided us all through the original. But at that stage, it was just the two of us playing them together — these were also great experiences, but it was the original game that brought a big group of us together for that one exhilarating night.

Resident Evil — like Final Fantasy VII in some ways — was an example of something that felt truly “next-gen” at the time. It opened with a then-terrifying (now utterly cheesy) live-action sequence, involving members of S.T.A.R.S. (Special Tactics And Rescue Service) who drop into a dense forest on the outskirts of Raccoon City. You are a member of the Alpha Team, and your mission is to investigate the disappearance of the Bravo Team, who were dropped into the area beforehand to investigate a series of murders in the area. After being chased by a pack of terrifying — and apparently rabid — dogs in the forest, you encounter a mysterious mansion in a clearing. The mansion becomes your prison for most of the game, as well as being an absolutely brilliant horror set piece, full of puzzles and all sorts of nasty undead things that are out to kill you. Even in the mid-nineties, Resident Evil was laugh-out-loud cheesy at times. The dialogue was often ridiculous, and the puzzles often made very little sense in the context of the world. And yet, you couldn’t explore the mansion without a constant sense of unease — a kind of ambient anxiety that only really lifted upon entering a save room.

To this day, I still love the Resident Evil franchise. The Resident Evil 2 remake, which was released just this year, is absolutely stunning, and it very much lives up to the original experience. I’m beyond excited for the Resident Evil 3 remake debuting next year, too.

My first experience with the PlayStation line was at a friend’s house playing the original console. I remember as a child being shocked with having not one, but two sets of shoulder buttons and wondering if I would ever be able to figure out how to play games like this. I honestly don’t remember the very first PlayStation game I played, but needless to say, it certainly wasn’t my last.

Demon’s Souls

PlayStation 3 (2009)

With Demon’s Souls, developer From Software attempted to do something new — in part, perhaps, due to the decline of the cult classic Armored Core series. Taking a page from their own King’s Field games, From Software experimented with a new kind of action RPG. The story goes that the developers were unsure whether or not gamers would take to Demon’s Souls — there was serious discussion around keeping it a Japan-exclusive release. But thanks to Atlus (a publisher with a long track record of bringing niche Japanese titles to the West), Demon’s Souls found its way outside Japan and quickly became one of the defining games of a generation (and the progenitor of blockbusters like the Dark Souls and Bloodborne games that would follow).

It’s an understatement to say that Demon’s Souls is important to me. This was the game that convinced me to buy a PlayStation 3 — and I picked up Demon’s Soulsitself around three months before I could afford the actual console.

There was nothing like Demon’s Souls at the time, especially from a Japanese developer. The game combined both RPG and action design along with rogue-like progression (the idea that enemies in an area would respawn upon the player’s death). This was the game that famously (or infamously) brought “difficulty” back to mainstream video games. It also birthed the popular sub-genre known as the “Souls-like”. Most importantly, perhaps, this was the game that finally gave From Software the mainstream recognition and accolades it so deserved.

As mentioned above, subsequent titles like Dark Souls and Bloodborne have achieved massive, mainstream success — but it’s worth remembering that Demon’s Souls started it all.

Disgaea: Hour of Darkness

PlayStation 2 (2003)

Coming up with three games that defined the PlayStation for me proved tougher than I thought. After all, these consoles helped to usher in a golden age of RPGs and other titles from Japanese developers. Originally, one of my three entries was going to be Devil May Cry 3 — but I wanted to use one of these precious entries to shine a spotlight on a series that really deserves more praise.

Disgaea, and by extension, Nippon Ichi, is an example of a developer — much like From Software — that has been around for a long time, but has struggled to find a global breakout hit. Disgaea is an example of another game receiving support from Atlus to make its way stateside due to the original developer not being able to do it on their own.

From the outside, Disgaea might look like any number of tactical strategy RPGs on the market. But what separates this franchise (and the rest of Nippon Ichi’s titles) from the pack is the sheer granularity of its systems. Each one of their games is built on a basic gameplay loop — but underneath that exist many layers of depth, especially in terms of the numerous subsystems involved.

Disgaea can be a 30–40 hour long campaign; it could also extend to hundreds of hours depending on how far you go building the most powerful weapons and characters you can imagine. It astounds me that the main gameplay loop can often take a backseat in Nippon Ichi games, in favor of exploring the depth surrounding it.

I’ve purchased almost every SRPG from Nippon Ichi ever since playing this game. The success of Disgaea definitely helped the developer to achieve success that enabled them to become their own publisher (they have since set up NIS America, their US branch). Ever since the debut of Disgaea, Nippon Ichi have continued to try to replicate its success with other RPGs and SRPGs — but they’ve also returned to Disgaea five times over, with a sixth entry planned for 2020.

If I was ever stuck on a deserted island, I’d gladly take the entire Nippon Ichi lineup with me; it’ll ensure I never run out of things to do. I can only hope the company achieves its “Dark Souls moment” at some point in the future.

Shin Megami Tensei: Nocturne

PlayStation 2 (2003)

The PlayStation platform has been a treasure trove for the JRPG genre. I must admit though, that I’d really quit looking at JRPGs during the original PlayStation era. I’d gotten tired of the general design, especially after playing the PlayStation era Final Fantasy games; I didn’t want to play the same gameplay loops and see the same story beats.

I found something different in Shin Megami Tensei: Nocturne. The SMT franchise has been around for a long time — and US fans did get the first two Personagames — but Nocturne was the first title in the central series to be released here.

While it may look like Pokémon from the outside, Nocturne is one of the toughest JRPGs ever released. Long before the franchise became stratospherically popular in the West (thanks to Persona 5), Nocturne invited players to enjoy a game where any random encounter could spell death for their party. Featuring both a mature storyline and the ability to grow and cultivate an entire party of demons, there was nothing like it on the market at the time.

Nocturne is a game of firsts for me. It was the first time I played a JRPG outside the more traditionally-popular franchises in the West, and it really introduced me to developers like Nippon Ichi — and of course, Atlus — which would influence my interest in the genre for years to come.

This was also the first time I would buy a strategy guide from the now defunct Doublejump Books, who made some of the best strategy guides of the era.

Nocturne is still on my list of games that I need to finish at some point. Despite this, I can credit it with getting me back into JRPGs, which is no small feat.

As a man in his 30s, the dawning of the PlayStation era was a transformative one. For several years prior, I had been at war with friends and family alike over who the real top dog of gaming was. My cousins were Super Nintendo fanboys, while we touted the raw power of our Sega Genesis. But when a new round of consoles made their debut, things got messy. I saw Mario swimming underwater in Super Mario 64 for the first time and was converted. But then there was this other thing, the PlayStation, with an ugly orange rat spinning in circles and running away from the screen. No thanks.

My opinion of the first Crash Bandicoot game never changed, but my feelings about the PlayStation did. I’ve since gone on to own and love every console in the PlayStation line — even the Vita. Its library of exclusive titles and definitive versions cross-platform ones has long made it my go-to gaming platform of choice. And while I’ve never rejected its competitors or their contributions to the industry, PlayStation has always felt like home. Over the past two and a half decades, Sony’s line of consoles have played a major role in some of the best and most significant experiences the medium has ever given me. Let’s talk about a few of the games that made that happen.

Final Fantasy VII

PlayStation (1997)

When Final Fantasy VII came out in 1997, nobody knew exactly what they were in for. Sure, it was the latest in the revered JRPG franchise, but that didn’t mean much in the West at the time. We take it for granted today — given the ubiquity of Final Fantasy in every corner of the modern gaming landscape — that this game would etch itself into the mural of game history. It was a perfect concoction of engaging turn-based combat, deep world-building, a fully realized story, and groundbreaking computer-generated cinematic cutscenes. It was not the first to excel at any one of these, but it might be the first to fire on all cylinders quite so expertly. Even 23 years later, as we encroach on 2020 and see Final Fantasy VII REMAKE waiting for us, fans around the world can only ask whether it can live up to its own legacy.

Having said that, I am embarrassed to admit that I have never finished Final Fantasy VII. It wasn’t for lack of trying, to be sure. Final Fantasy VII was the game that convinced me to buy a PlayStation, after all. My parents refused to spend money on another console for us after they had already scraped together enough for our Nintendo 64. So my brothers and I sold enough of our Magic cards, Pogs, and other junk to afford one ourselves. As any youngest sibling would know, playing games as a kid frequently meant watching somebody else play. One of my brothers who had commandeered the PlayStation for his own playthrough of Final Fantasy VII had been lulled into the game’s Gold Saucer minigame (unlocked in disc 2), which involved racing and breeding chocobos for better and better rewards. Some of the game’s very best materia required the Gold Chocobo, which could only be attained through the Gold Saucer races and an esoteric breeding process. We needed help.

At school, there was this kid who wouldn’t shut up about Final Fantasy VII, even though none of his friends gave a shit. By the time my brothers and I had got our copy of the game, he had completed it three times. He was the only person I knew of that actually had a Gold Chocobo, so I introduced myself on the playground, and by the next day he had drafted a detailed map of the chocobo breeding process my brother needed. He very quickly became My Friend Who Plays Games, and eventually my closest. In 2010, we made our own throwback to classic JRPGs like Final Fantasy VII (which you can play for free right here). He was my best man in 2011. In 2016, he started his own company, and I became his first employee.

I don’t think my brothers and I ever unlocked a Gold Chocobo. In over twenty years of starting and restarting the game each time a port comes to a new platform, I’ve never made it to the third act. At this point, it’s probably too late to fix that. But in spite of this, Final Fantasy VII has had a more profound impact on the course of my life than any other game before or since.

Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater

PlayStation 2 (2004)

Metal Gear Solid is probably my favorite video game series. Many of its instalments pepper my top picks of all time, and Metal Gear Solid 3 is my favorite among them. It’s fitting, then, that a series so entrenched in the narcissism of its creator would find its way into my world on the tails of my own ego trip.

I was a big fan of gaming magazines in the early 2000s. The internet was still not up to par with the kind of exclusive content that gaming magazines were securing at the time, so being kept abreast of the latest news and earliest reviews necessitated at least one monthly magazine of your choice. I favored EGM, which at the time was populated with colorful personalities amongst its staff. I would often read the Reader Mail section and scoff that I could say something funnier than what was submitted, or do a better job than the majority of the fanart featured. I frequently sent mail that would never grace those pages (in part because it didn’t occur to me that sending mail about the current gaming news landscape would be irrelevant by the time the next issue would be printed). That is, until it did. I don’t remember if it was a picture I sent or a message that made it into the magazine (it wasn’t the last time I sent them worthless fan mail), but I remember being so thrilled standing in the magazine aisle of Barnes & Noble, seeing my name in the latest issue. The issue, as it happened, was the Holiday 2004 issue of EGM, featuring the gorgeous cover art for Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater. I probably wouldn’t have read that review had that issue not been so notable to me. My interest was piqued, and I rented the game that Friday.

I couldn’t tell you why I stuck with the game initially. It was nothing at all what the review had led me to believe. Fixed, top-down camera, bizarre supernatural elements, goofy personalities, overwrought dialogue, all took me by surprise after reading a review for what looked like a military stealth action game. Of course, this was probably how players felt picking up the previous entries to the series for the first time. And like those fans, I was slowly enthralled by it. There are very few pieces of media that can straddle the line between quirky irreverence and heavy emotional drama quite so expertly as Kojima’s work, and Metal Gear Solid 3 might be his greatest achievement in that balancing act. It’s a game that you can somehow reconcile has soldiers pooping their pants and grabbing each other’s crotches, while also exploring to tragic effect what it means to sacrifice yourself for an ambivalent government.

I’ve since played the rest of the series, and I’ve returned to this one more than any other. I may have missed the first time through how much of the game references, winks, and alludes to moments in the instalments that came before it, but as a prequel to the overarching narrative, it worked very well as a starting point for newcomers like me. Who’s to say if it’s the best game to come to a PlayStation console, but it is definitely my favorite.

The Last of Us

PlayStation 3(2013)

I didn’t want to put The Last of Us on this list. I knew my colleagues would have far more compelling things to say about this game, and what else can really be said about a game many would consider the best of the decade? And yet, as I thought about the games that have resonated with me and affected me so much in the 25 years since Sony unveiled the PlayStation, I kept coming back to Naughty Dog’s magnum opus. The thought process was always the same: What game had the best story — besides The Last of Us? What had the most compelling heroes — besides The Last of Us? What did the most with its hardware — besides The Last of Us? This is a game that we have to actively ignore when thinking of superlatives, lest we repeat ourselves.

But we have to repeat ourselves. When a studio creates a masterpiece, we don’t have the luxury of ignoring it for the convenience of an engaging list, or to make things more fair for others. When Naughty Dog dropped The Last of Us into our laps, they delivered a game that exhausted every drop of processing power the PS3 had to offer, and took advantage of every trick in the toolbox to achieve it. They invented new tricks and discovered clever solutions that the rest of Sony’s studios have borrowed from since. They used every inch of hide and every ounce of fat to render a world that could sell the story they wrote, and the faces to speak those lines, and the eyes to make us believe it.

None of this would matter if the story wasn’t there to deliver, but it’s through the story that we can understand why this team was so dedicated to succeeding in this impossible mission they were presented with. In a medium where gameplay has always guided a story’s structure, The Last of Us lets the narrative lead the way, and builds its interactions upon that foundation. We feel confident that we are where we are because the characters dictated it, and not because we’ve hit the next set-piece in the roadmap. It takes its story seriously, and it commanded a team to defy the limits of its genre and its hardware to tell it in a way that could do it justice. The result is a game that, as much as we may try, we can’t ignore.

My first experience of PlayStation was when I was perhaps 8 years old. I was at a kids play area and alongside the ball parks and slides, they had three PlayStations set up with Crash Badicoot, Lucky Luke and UEFA Striker. It wasn’t long before I found myself absorbed in these three titles, enamoured by the graphical fidelity of the console.

Crash Team Racing

PlayStation (1999)

While the original Crash Bandicoot was the first game I ever played on a PlayStation platform, it was with Crash Team Racing where I ended up spending most of my time. Forget Mario Kart or Diddy Kong Racing, Crash Team Racing’sinnovative drift system and complex tracks had me hooked.

Given that I was perhaps 11 years old, and still in school, Crash Team Racingquickly became the game of choice for me, my sister and our friends. Almost every day I’d hop round to a friends house to play a few games of Crash Team Racing with a friend, and often their siblings. The game was so engrossing that even our mum used to practice in secret just so that she could try and keep up with my sister and I when we would come home from school.

To this day I still play Crash Team Racing. Up until recently I was playing occasional races through the emulated copy on the PlayStation Vita. But Crash Team Racing Nitro-Fueled has since taken its place. This updated version of the game is a true love letter for fans like myself and my sister who grew up with the game.

Twenty years have passed since the original Crash Team Racing but we’re still playing. My mother, sister and I all have copies of the remake on our PlayStation 4, and while we’ve all moved forward with our lives, Crash Team Racing Nitro-Fueled’s online play helps me keep in touch with my sister, chatting online as we race around the same tracks that we did as kids in 1999.

LittleBigPlanet

PlayStation 3 (2008)

LittleBigPlanet is the video game embodiment of a hug. Sackboy and his universe are so cheerful and content that it’s hard not to feel happy when playing through the levels that Media Molecule have created. For me, LittleBigPlanet offered an opportunity to relax and unwind.

This game also taught me that anyone could be creative, that anyone could design a level, or even create a game. Itss motto — play, create, share — gave me confidence to be creative within a space that I felt comfortable, and an area where I wanted to see my ideas realised. The experience of building levels and experiencing others in LittleBigPlanet was both gratifying, as well as something that I believe was beneficial to my mental wellbeing.

LittleBigPlanet and its sequel really changed the game in terms of what the player’s role is. By empowering players as creators and artists, LittleBigPlanet set the stage for a whole slew of games built around the “play create share” mindset, from Super Mario Maker to Soundshapes. Meanwhile, Media Molecule’s new title — Dreams — is even more poised to empower the player as a creator and game developer, with its robust creation tools. I can’t wait to see what people make in Dreams, but I hope we haven’t seen the last of Sackboy and LittleBigPlanet.

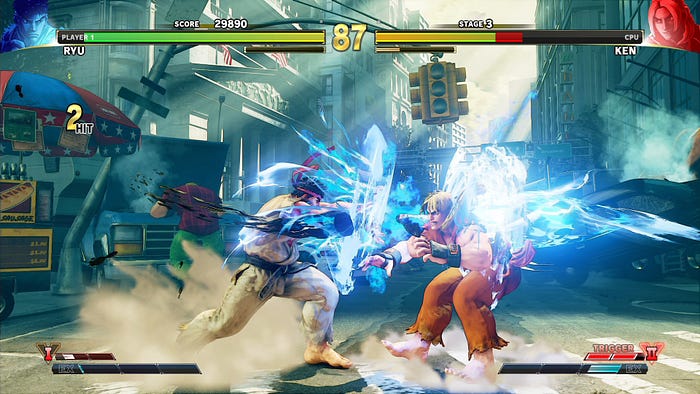

Street Fighter V

PlayStation 4 (2016)

Similar to my experience with Crash Team Racing, Street Fighter’s appeal has been as much in the social experiences I’ve had surrounding it as the game itself. While Crash Team Racing became a shared activity for my family, Street Fighter became a platform for meeting new people, and joining new communities.

When Street Fighter V came around, I had just setup the fighting game community in my local town and both myself and my friends were ready for a new game. Street Fighter V may have its share of issues, but it provided a compelling platform for competitive play that kept me and my friends engaged week on week.

Street Fighter V itself provides an expansive roster of characters each with their own move sets, qualities and playstyles. The package was barebones at launch, but for us the versus modes were more than enough. Each week we played we saw new rivalries and upsets, and the game provided a platform for those experiences; it was through this game that I made many of my closest friends.

After University I began moving across the country to work, then to different countries as I moved overseas; every city I travelled to had a Street Fightercommunity that I embedded myself in. In Montreal, the community lost its venue, so people started playing in my flat instead. Sixteen player tournaments hosted across 3 setups in a 2 bedroom flat; it was wild.

Ironically, my PlayStation experience has not been dominated or characterised by exclusives. My entry point to the PlayStation family was the timeless PlayStation 2, a console that exudes power and grace equally to this very day. My all-time PS2 favourites are filled with the likes of games such as Burnout 3: Takedown (which I still think to this day is the greatest game ever) and Shrek 2,but neither of these were exclusive. After skipping the PS3 for the (clearly) superior Xbox 360, I became a turncoat yet again, getting a PS4, of which my most played game has been by far the NBA 2K series. Despite the lack of devotion to PlayStation exclusives (I’ve never played Final Fantasy or Metal Gear — forgive me) here are three of my favourites, even though there’s not a heap to pick from.

Death Stranding

PlayStation 4 (2019)

I’ve clearly not played enough PlayStation exclusives when a super recent game like Death Stranding makes my list. That being said, Hideo Kojima crafts a masterfully exotic and foreign world in Death Stranding, a place that is supposed to be a once decimated America, but more resembles what one would encounter on a wilderness tour in Iceland.

Having never played a Metal Gear game, I was (and still feel) pretty ignorant of Kojima’s taste when creating games. There were many times when a question like, “what the $%@ is going on?” were simply answered by the fact that it is a Kojima game.

I want to be more brief when discussing Death Stranding as I don’t want to spoil anything from the game as it hasn’t been out long, and also because I will soon be undertaking the task of attempting to “review” the game, even though it’s probably impossible in a conventional way. After all, Death Stranding is anything but conventional.

Before I received a copy of Death Stranding to play, I had heard basically nothing about it. When it comes to films and games, I usually don’t follow any news cycles (unless it’s CyberPunk 2077). All I knew about Kojima’s latest title was that Norman Reedus starred in it, and I loved him in the first few seasons of The Walking Dead that I watched.

Even though expectations were null, I still had a sense of anticipation about what Death Stranding was going to be. I could tell from about thirty seconds in that it was setting itself up to be a wide-reaching and cinematic experience. As Sam Porter Bridges, you are tasked with travelling across the decimated America in order to connect up scattered colonies with the chiral network.

Its strengths and weaknesses are perhaps more identifiable than my other two PlayStation favourites. At times Death Stranding can be pretty laborious. There are too many lulls while playing, something that really shouldn’t happen considering the complexity and depth of the narrative. It also suffers from utilising far too many metaphors and moments of symbolism, which often just comes off as trying to be pretentiously clever.

When it comes to its strengths however, Death Stranding shines a bright light. Aesthetically it’s a masterpiece, rivalling Shadow of the Colossus in its beauty, except it’s far more vast and unique in its complexion. The character models are as good as I’ve seen on PS4, with facial movements and expressions being idiosyncratic and minute. It’s crazy how far gaming technology has come in the past decade.

Despite taking me 33 hours to finish — the longest game I’ve played in a long time — and making me incredibly frustrated often, Death Stranding still creates an ambitious and powerful experience within a striking world that could one day resemble ours.

Shadow of the Colossus

PlayStation 2 (2005)

It should probably be considered cheating that two of my top PlayStation exclusives are games that were actually just remasters of the original game. In this case, Shadow of the Colossus has actually been remastered twice, originally released on PS2, and subsequently released on PS3 and last year PS4.

Created by the same team as the equally acclaimed Ico, Shadow of the Colossus takes place in a desolate world, where a young man named Wander must defeat sixteen colossi in order to save a girl’s life. It’s a deceptively simple plot, but one that is handled expertly to create another breathtaking experience.

When you Google, “video games as art,” there’s a reason that Shadow of the Colossus often pops up as one of the preeminent examples of the aesthetic value that video games can present to society. And that’s from when it was released back in 2005 on PS2, not to mention the vast graphical improvements that the PS4 remaster features.

I had never played Shadow of the Colossus prior to when I played it on PS4 to review for SUPERJUMP last year, but I was amazed by the world that Fumito Ueda had created. Even on my standard PlayStation 4, the graphical update was incredible, and I imagine it would be even more delicious on a 4K TV on the PS4 Pro.

Beyond just aesthetic appeal, Shadow of the Colossus is one of my favourite PlayStation games because of the gentle and powerful way it communicates emotion and thematic concerns throughout the game. Each colossus you come across has the air of grim morbidity, an atmosphere of grief and loss.

Likewise, the gameplay is equally great. Despite the controls sometimes being frustrating, the way each colossus presents itself as a different puzzle is exceptional. Different tactics are required to defeat each creature. Some are larger, some are quicker and some are airborne.

By all accounts, the PS4 remaster is a faithful and sound revival of the original game. I’d wage it’s probably not a coincidence that IGN ranked both the original PS2 game and the PS4 remaster the same score at 9.7/10. It’s a subtle nod to Bluepoint Games’ work on the remaster. Balancing improvement and authenticity is no easy job.

In many ways, Shadow of the Colossus was way ahead of its time. It symbolises a gaming experience that lies as an antithesis to what has dominated the video gaming landscape for the past decade — large-scale, extravagant and increasingly intense games. The minimalism that permeates Shadow of the Colossus is remarkable considering the, well, colossal nature of the game’s undertaking.

Those looking for a different experience with incredible artistic and thematic depth should do themselves a favour and check out Shadow of the Colossus.

The Last of Us Remastered

PlayStation 4 (2014)

Naughty Dog was already a household name by the time they released The Last of Us. Best known for the Crash Bandicoot and Uncharted series, they’ve become one of the most iconic and recognisable developers, thriving as a subsidiary of Sony Computer Entertainment. With The Last of Us Part II set for release in mid 2020, it’s probably time I go for another play through of the first game.

The Last of Us Remastered was, as far as I remember, the first ever game I preordered. It’s safe to say the buzz it had garnered in the short time it was available on the PS3 definitely caught my eye. I had never experienced such emotional intensity in a video game before, and The Last of Us Remastered was an enormous tidal wave of feels.

I was expecting a typical zombie shooter game, but what I experienced instead was perhaps the realest story of humanity possible. In a world full of the undead, the scariest beings you encounter end up being the people you thought were just like you. Even though I was probably a bit young to properly appreciate themes of The Last of Us Remastered, I understood enough to be strongly touched by playing it.

Play as the stoic Joel, a smuggler who has to take Ellie, a loveably belligerent teenager, across the post-apocalyptic United States, twenty years after a mutant fungus has swept through and decimated the entire country. Much of the game centres on the developing connection between Joel and Ellie, and their respective pasts and secrets.

Don’t forget that The Last of Us Remastered is as brutal in its gameplay as its thematic intensity. I constantly got stuck on different sections, unable to figure out how to defeat particular enemies, or how to get through many of the unique areas you traverse. On more than one occasion I called in reinforcements from friends who had already finished the game to assist me. 9/10 times you should tread carefully and avoid the attention of the waves of zombies ready to feast on your flesh, but the one time you should be decisive and aggressive always catches you off guard.

The Last of Us Remastered also included the prequel expansion pack, The Last of Us: Left Behind, which despite being brief, aided in deepening our understanding of Ellie as a character. It received particular praise for its story and depiction of LGBT and female characters, praise that the full game itself also garnered.

Even though at times the experience can be burdensome and cruel, The Last of Us Remastered left an indelible impression on me personally, something that most games simply aren’t set up to do in the first place. Naughty Dog once again showed us all how video games can push the envelope of what is considered a “consumer entertainment experience” and craft something unique and powerful.