Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter - Climbing From Hell to Heaven

Understanding the "lost" Breath of Fire game

It's difficult to properly evangelize an underrated game twenty years after its release. Words do little justice for solo epiphanies against a deluge of yearly releases. Finding an older game that really moves you often feels like finishing an incredible, life-changing novel; when you're done, you're still sitting in a room by yourself.

Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter, released in 2003 to endless criticism and moderate reviews, has fallen to the abyss of time. Outside of emulation or original ownership, there is no way to access the fifth entry in the classic Breath of Fire series from Capcom. It's as if with this final game (mobile sequel notwithstanding), the series was chucked into a vast silo and buried underground.

Maligned for its departures from story, deviations from brand, and diversions from tradition, Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter has hardly enjoyed prestige as a cult classic. It is, in essence, a great lost game—one of many that have neither the power nor the traction to claw their way to the surface of a modern gaming library. With a soundtrack by Hitoshi Sakimoto (Final Fantasy Tactics, Final Fantasy XII) and art direction by Tatsuya Yoshikawa (Breath of Fire I-IV, Devil May Cry 4 & 5), playing this game so many years later feels a greater sin than just overlooking an eclectic classic—this title deserves heaping praise. Dragon Quarter has died in obscurity, its bones skewered to an iron wall to gather dust.

A Black Mile To The Surface

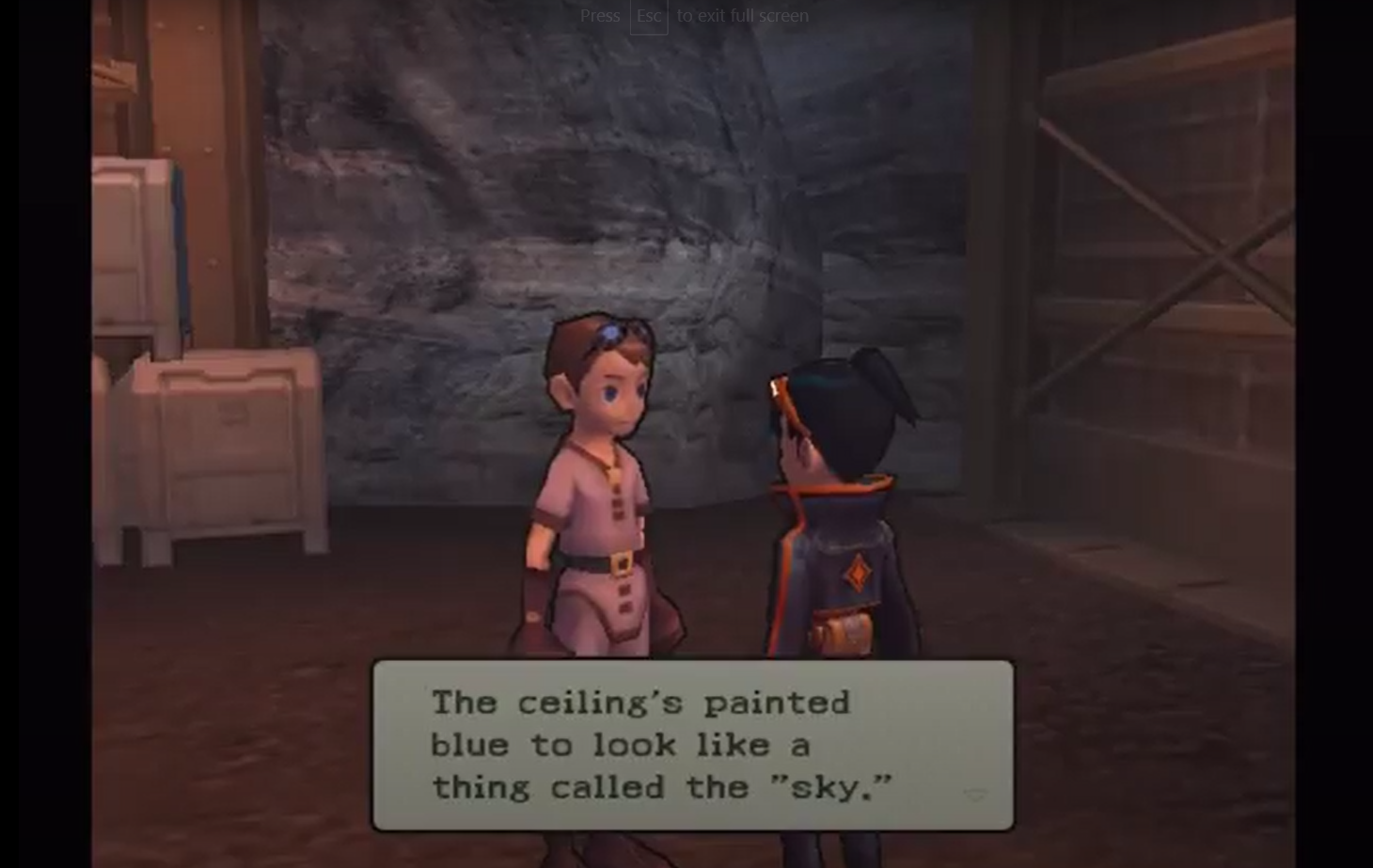

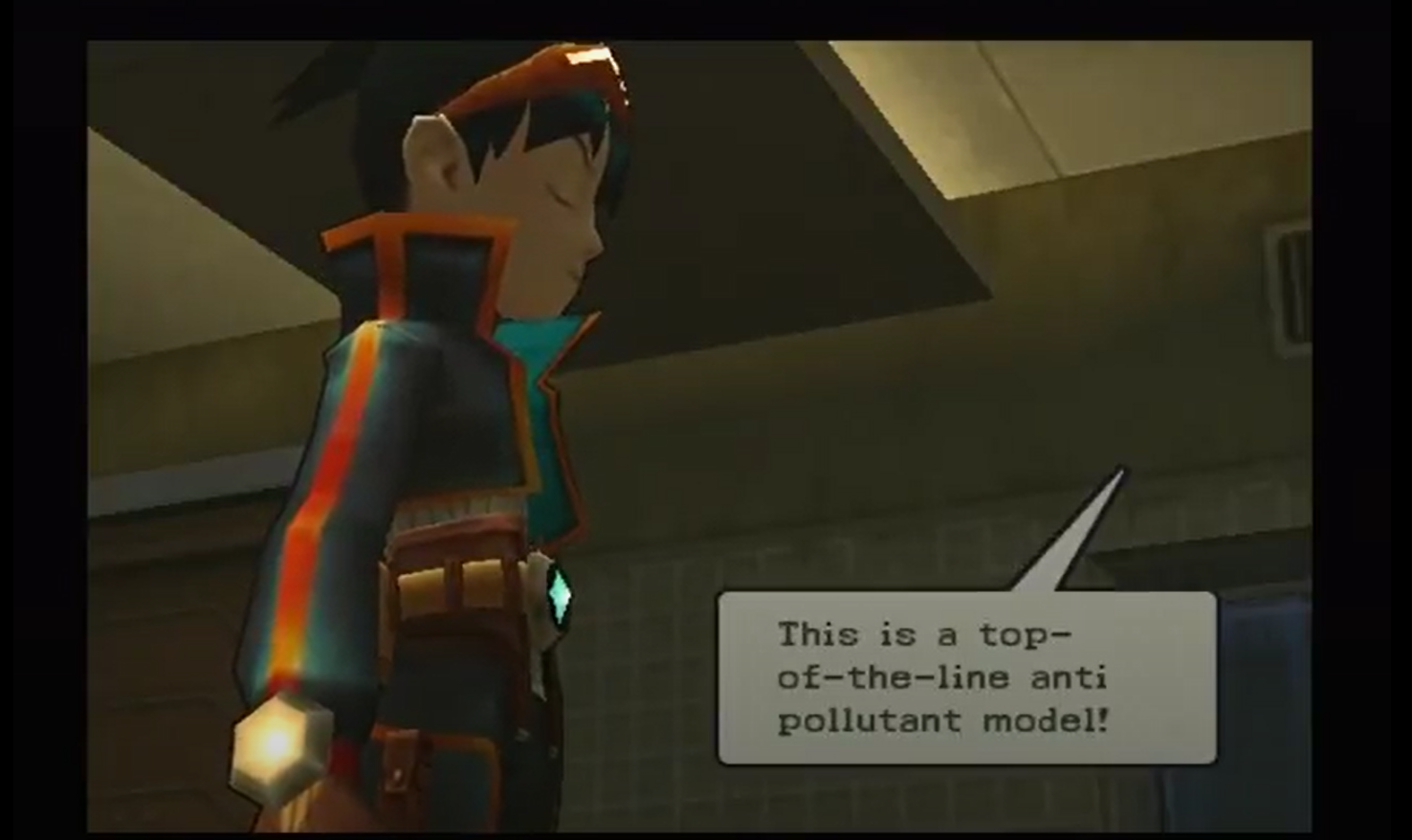

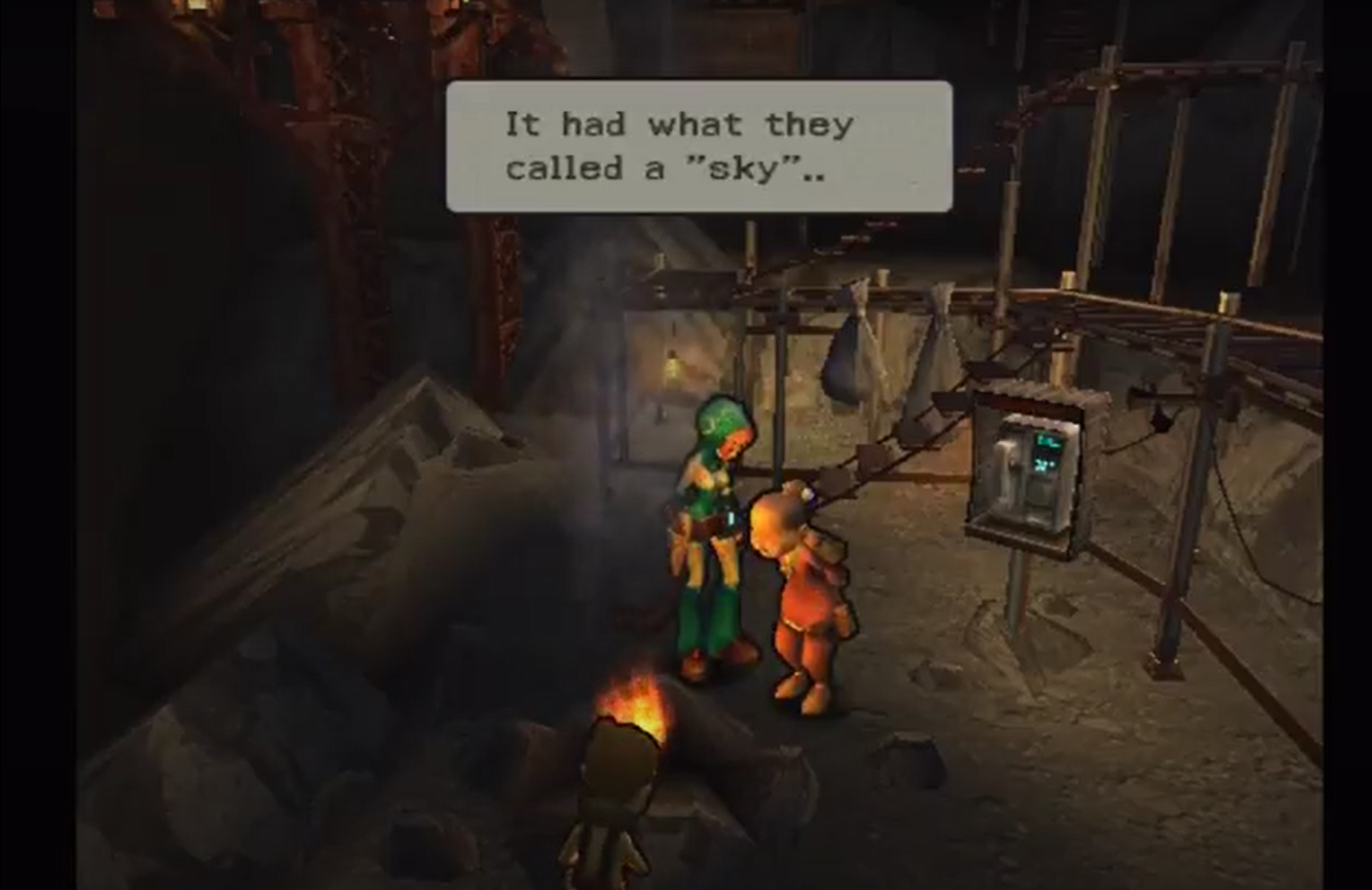

The upper world is gone, lost to calamity. Buried a kilometer beneath the ground, humanity struggles in a caste system assigned by a mythological standard. Every human being born in the labyrinth of this new society is given a D-Ratio, a ranking number out of thousands that is determined based on the likelihood of linking consciousnesses with the dead dragon Odjn. Citizens with the lowest D-Ratios are banished to industrial townships without an ounce of greenery, places built into caverns with artificially-painted skies. Citizens who cannot, or will not, fight against the course of their assigned ranks will live and die by their D-Ratios, succumbing to disease and malnutrition while the higher-ranking citizenry enjoys lives of luxury hundreds of feet above.

Ryu, an unlikely Ranger with an abysmal D-Ratio, is subject to the caste system and takes his assignments to stay alive. Tasked with routing out members of Trinity, a counter-insurgency attempting to undo the status quo, he and his partner Bosch head out through the confines of their underground base under military direction. Through a series of unlikely events, Ryu becomes uncoupled from Bosch and is joined by the quiet Nina and the boisterous Lin. Together, this trio heads upward through danger in search of the mythical sky.

Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter is bespoke with political criticisms and societal reflections. The broken ideologies of various fascist systems blend together into a singular corrupt entity more terrifying than any dragon or god. What Ryu and his friends fight against is not so much a physical threat—though there are enough of them—but decrepit normalcy that's baked into the standard of their lives. Evocative of Bong Joon-ho's 2013 film Snowpiercer, there are only two options: move forward against the machine, or die. There is only the upward momentum, the ever-crushing agenda of horrors waiting for them, the multifaceted threats of monstrosities and self-appointed nobles waiting in ambush. Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter fictionalizes a common living struggle, stripping away the fluff to reveal social barbarism.

Once Again, To The Sky

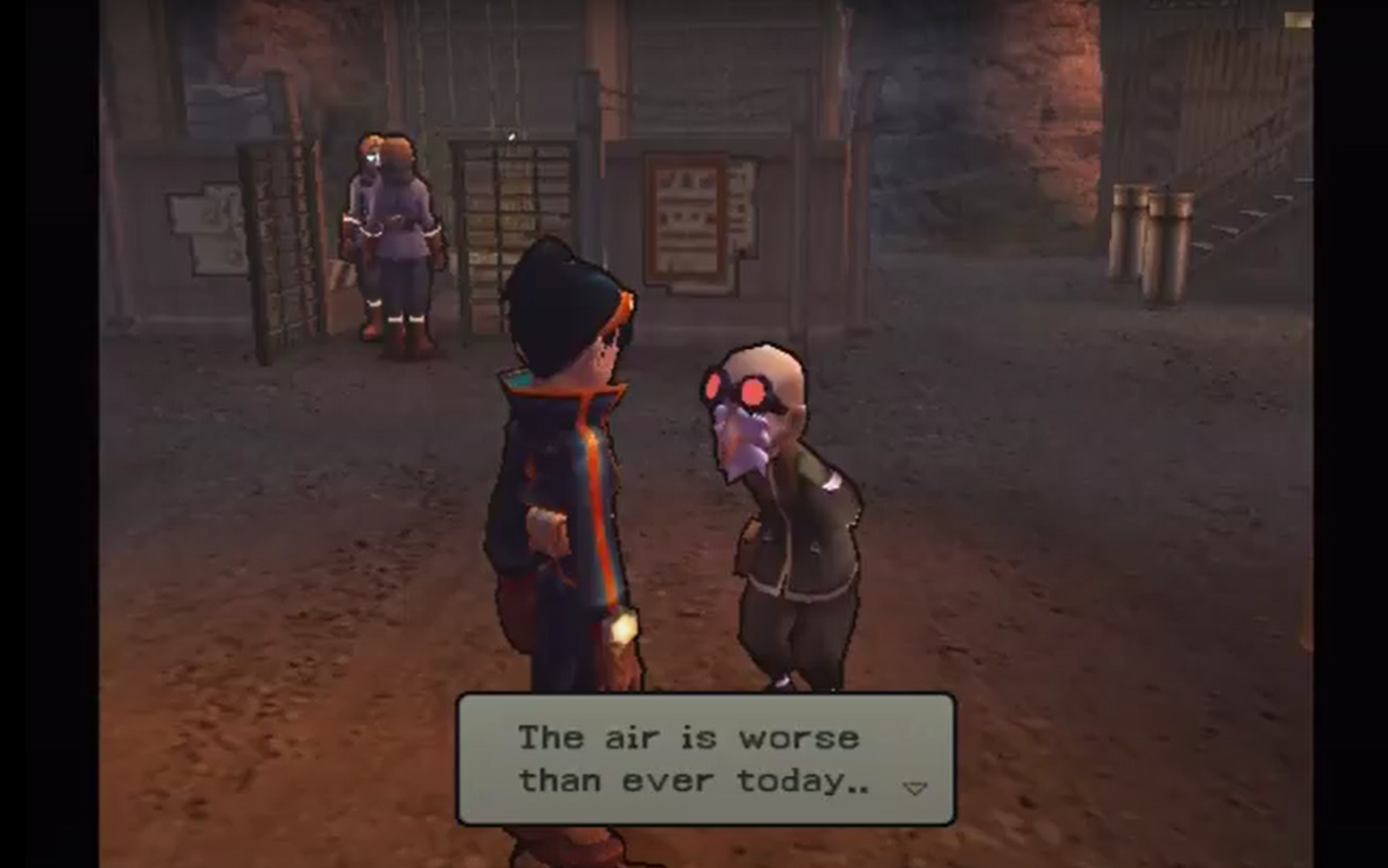

A terrible calamity befell the world. The dragons, beings of great hope and despair, succumbed to their own mortality and doomed humankind. While Dragon Quarter only gives us a glimpse into what is happening in this single bunker, it is a believable nightmare. The world of Dragon Quarter is oppressive, sterile, ruined. While so many RPGs occur in lush environments and diverse biomes, Dragon Quarter takes place almost entirely in an industrial wasteland. Room after room of warehouses, ruined offices, abandoned cities, all buried beneath the ground. As Ryu, Nina, and Lin continue to make their way toward the surface they are shown the truth in layers, unlivable squalor rotting away. The status quo that the Rangers protect is dwindling, the very infrastructure of their lives falling into disrepair. The unsustainability is made plain as they climb up the towering labyrinth, finding nothing in the way of respite. It's a bleak, atrocious, miserable slog that again and again reinforces the cruelty of their socioeconomic system, and how this escape from the surface only paralyzed the lives of the remaining human population.

Somehow, despite his low D-Ratio, Ryu gains a godlike miracle. Blessed with incomparable dragon powers, Ryu becomes a corruptible force alongside the diverse combat abilities of his two female companions. This is one of the resounding positives of the genre, the ragtag group of unlikely heroes uniting together against overwhelming and oppressive forces. Never before have I seen a JRPG pull off this storytelling device to such shocking believability—the chance of failure that exists in Dragon Quarter is not only echoed by the circumstances and story, but by the gameplay itself.

Furthering its departure from RPG norms, Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter is impressive for its era. Dragon Quarter is ahead of its time, infused with many features that have become standard such as its roguelike mechanics. The game demands you fail, but blesses you every time you restart. Save points are few and far between, hampered by the fact that you need a consumable item to use them (à la classic Resident Evil). Death itself is different here—when you die, you are given the option to return to your last save point with a percentage of what you have gained, or restart the entire game with some of your items, weapons, and stocked experience. It's a gameplay choice that felt frustrating in 2003, but in 2022 it makes for an extremely addictive formula not far removed from Hades, Dark Souls, or Dead Cells.

Like many masterpieces, Dragon Quarter's enjoyment improves if you eject all sense of expectation and engage with it on its terms. While the concept of restarting a save file in a JRPG multiple times might sound daunting, it's surprisingly refreshing. Finishing the game the first time requires less than 25 hours of your time, and with every restart, you glean new items, new equipment, and even new cutscenes that flesh out the lore of Dragon Quarter's mysterious calamity. What's more, New Game Plus players are awarded an entirely new batch of cutscenes that build upon the track of what's already been experienced, with gameplay made massively easier by the weapons and skills you acquired on the first play-through. It's an addictive formula that drives a completionism mindset, but unlike games such as Chrono Trigger or Elden Ring, there's more to see than a new ending. New Game Plus feels like an annotated version of the game.

Ryu's Ladder

In 1990, Ted Chiang published a story titled Tower of Babylon (if you have not read this incredible short story, please take a break from this essay, read it, and return). While Ted Chiang might be better known for the story that was made into Denis Villeneuve's melancholy science fiction film Arrival, Tower of Babylon might be his truest example of personal effort in the face of corrupting knowledge.

In Tower of Babylon, a miner has been summoned to climb the eponymous tower. Constructed to reach the domain of Yahweh, the tower is the greatest testament to human innovation, ingenuity, and determination. The miner and his colleagues must ascend the tower in order to break through the firmament and finally meet their God. The miner, facing perils, finally reaches the top of the tower and breaks through the resisting barrier. What awaits him is a shocking punishment: he is returned to the base of the tower, the Vault of Heaven is revealed to be a tesseract and the entire world a repeating reality.

In Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter, Ryu and friends climb this inverted Babel for a reward of their own design. Ryu, Lin, and Nina have never seen the surface. They have no reason to believe such a thing as a "sky" even exists, or that there is an actual end to their ascension. They climb floor after floor, battling monsters and men, resisting sabotage and sickness, all on the belief of a better life. As Ryu is continuously corrupted by the power of his dragon, the truth of their calamity is laid bare. The unending journey through decrepit rust-colored industrial rooms comes to a sudden end as they are greeted by a blue darkness of clean metalwork, platforms, and electronic devices. The more they head upward, the fresher life becomes. While their journey pushes through the strata, the player is shown evidence of ancient corruption buried deep. Like the caste system itself, everything that sits on the bottom is abandoned. With every meter closer to the surface, it becomes clearer that the resistance formed against them is one built out of fear of change and lost status.

There is a striking violence to Dragon Quarter that goes beyond its surrealist imagery and aesthetic barbarism. The oppression of this game is very real, drawn out between the Haves and the Have-Nots. While those closer to the surface, The Regents, have power of their own to protect, they too are buried beneath the closed lid of society's casket. The powers that be, led by Elyon and corrupted by Bosch's dragon Chertyre, are determined to prevent Ryu from succeeding because his success would fly in the face of the cruelties they have baked into their beliefs. Elyon, Odjn's first, is a mark of unique failure—a testament to succumbing to fear and upholding the standard even when the standard is nothing but bleak misery. As the player reaches the final bout of the game, one mere final cutscene cannot do justice as any true reward. Whatever lies beyond the ancient gates—whether it's blue sky or utter calamity—may not be upheld by the effort of their journey. While the final moments of story slowly peel back expectation, a hopeful future is largely left to player imagination.

Illusion and Experimentation

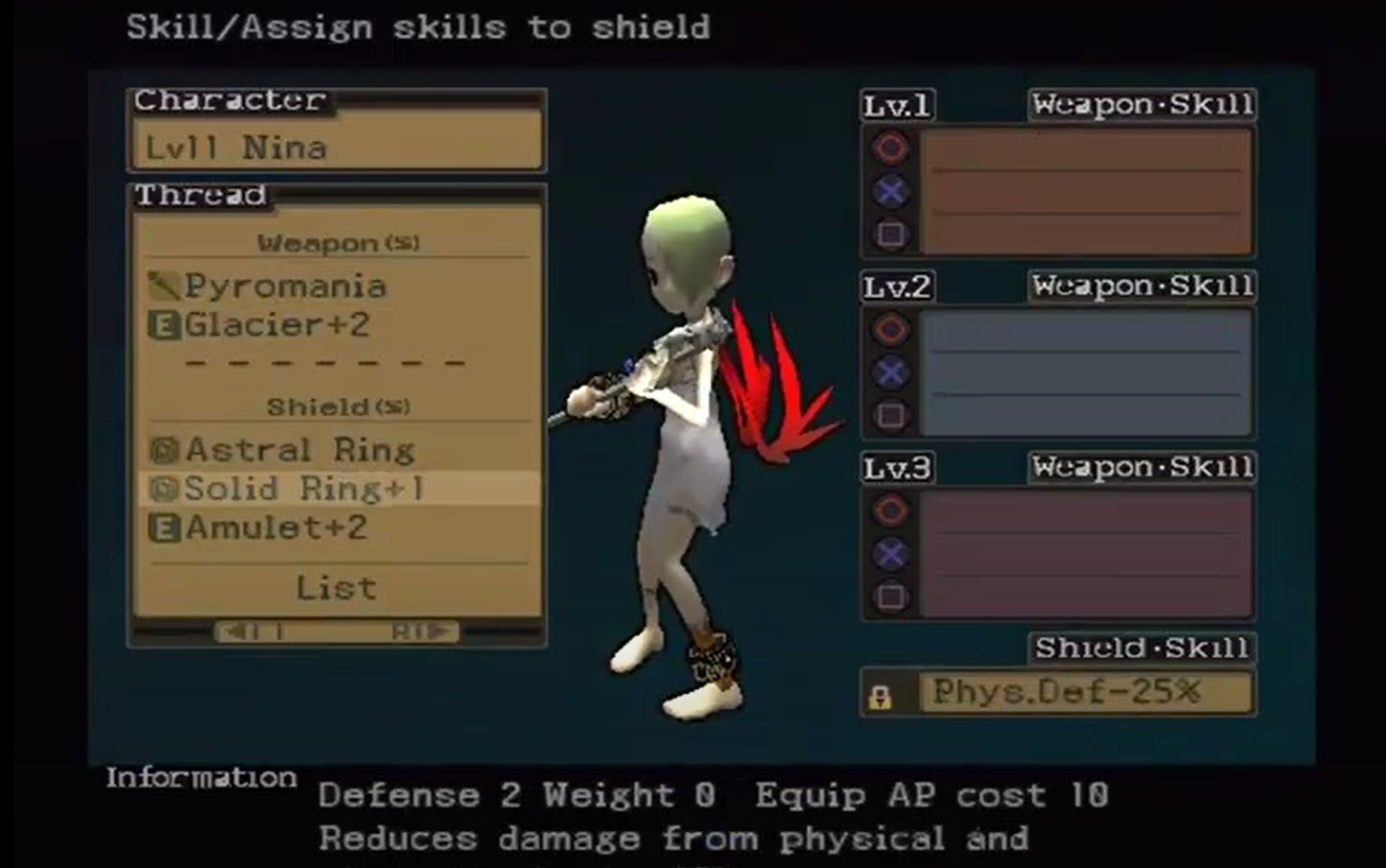

Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter's greatness is reinforced by how well it adheres to its plot and subject in story and gameplay. As in Vagrant Story, experimentation is encouraged and expected—you won't know what spells or attacks will work on an enemy until you try them, and the disparity between an effective attack and an ineffective one is vast. Gameplay diverges from turn-based combat by existing on a level of strategy: characters are given AP each turn that is drained by both attacking and movement. Skills can be assigned and chained together, and weapons are hugely important. Every single encounter seems to run by its own rules, with some characters eking out power over others depending on the monster type. Boss battles are cruel and unforgiving, reinforcing the game's determination in driving you down and forcing a restart. There are many moments where bosses can feel outright impossible until you realize how limited you are by both abilities and resources—something that doesn't exist as much in the modern era. It's likely to enter a battle so completely unprepared that it's simply impossible to move forward. You must restart, and try again.

Dragon Quarter ratchets up the intensity with a perma-death feature that cannot be escaped. Similar to the end of the third day in Majora's Mask, there is a constant threat in Ryu's D-Drive. After his consciousness unites with Odjn's, Ryu is granted terrible and awesome dragon powers. These essentially transform him into a physical god anytime they are used, but there is an enormous catch. In the top right of the screen hovers a counter that is eternally counting upward toward 100%. When this gauge hits 100, Ryu will be ripped apart as a dragon emerges from within his human shell like a butterfly tearing bloodily through its cocoon. Although this gauge fills from dragon actions, it cannot be undone during a single playthrough. More anxious players might be deterred by this death count—it's possible to reach the very end of the game and lose your file from mismanaging your dragon actions and racking up too high a D-Count. Dragon Quarter's difficulty, while punishing, is not supposed to be in itself a punishment—the considerations are made knowing you can begin again.

Its cyclicality is born in the nature of what the game is, or was trying to be. You battle ever upward, one room at a time, fighting monsters and horrors. You collect items and pray that there's a Save Token somewhere in the next few rooms. You stock up on healing items, praying that it's enough and that the game won't sic another back-to-back boss fight on you. Where Dragon Quarter shines is in its masochistic determination to drive you down, to make you feel like the ascension to the surface is not only impossible by the story's terms, but by the game's. While many video games have perfected this back-and-forth of risk and reward in the last decade, this level of true difficulty feels awkward against a library of Playstation 2 RPGs that were much more story-focused. Dragon Quarter feels like it's not only rebelling against the conventions of the RPG but its very nature.

Visions of the End

At the time of this writing, in Washington state, air levels are so polluted by wildfire smoke that the breathable air is considered toxic. For weeks we have endured daylight wreathed in an ocher film, drowning out a red sun while we enjoy an uncommonly hot October. It's difficult to live in these times and not envision the looming end, whether it be from true apocalypse or climate change. It's unsettling to attempt a life without knowing whether or not there is a future that carries any brightness.

In Dragon Quarter, humankind is undone by its own hubris. The "dragons" that are locked belowground with humanity are artificial weapons of mass destruction crafted a millennia ago in hopes of winning a war that's no longer covered by any existing history book. In efforts to bring salvation to themselves, the humans destroyed their own world and buried themselves in hopes of a second chance at life. The Regents who control the caste system of D-Ratios reinforce and police the status quo as if they are protecting misremembered ghosts, and the past haunts them as they adhere to a falsity that only burdens the people that remain.

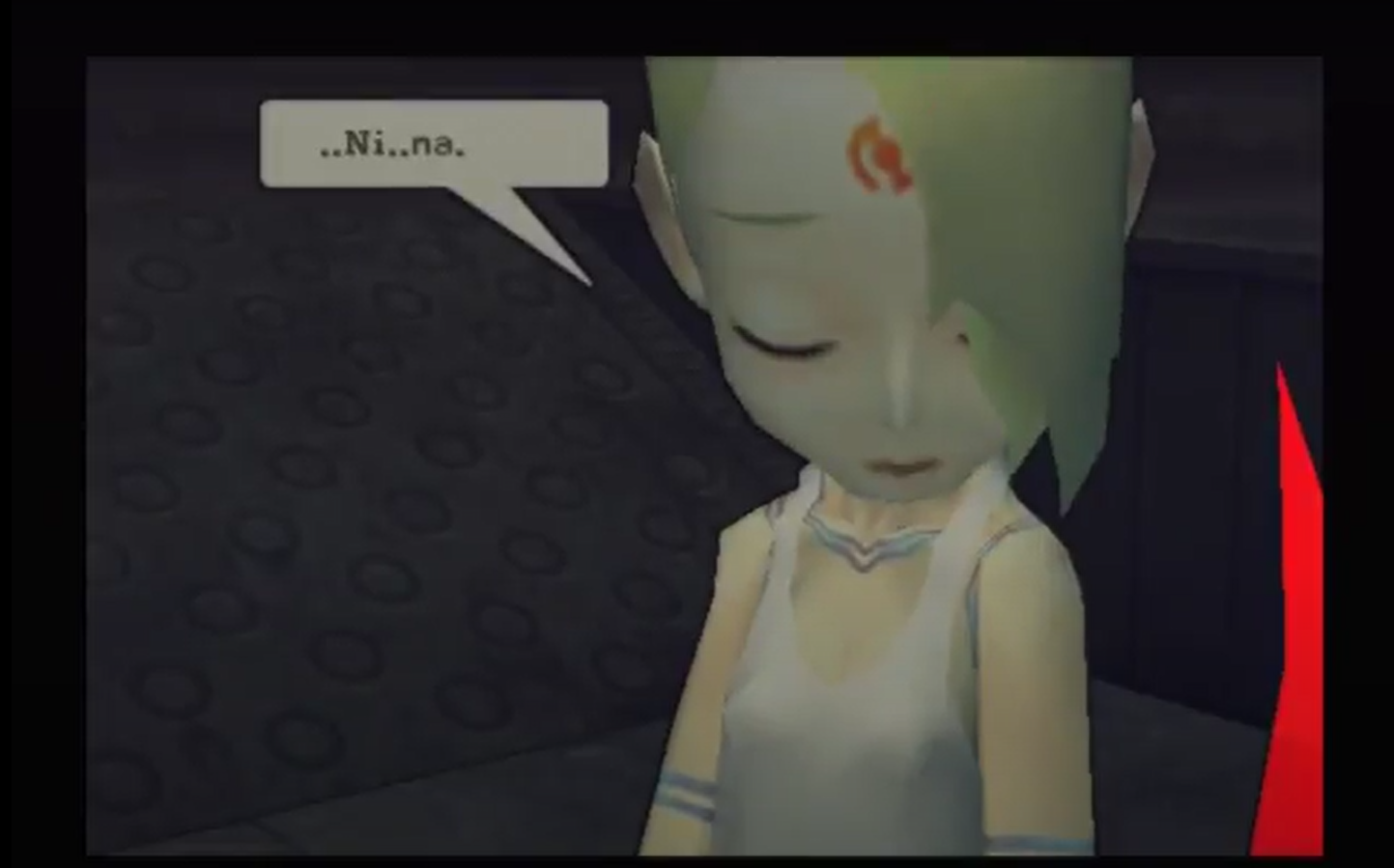

Upon meeting Nina, Ryu is struck by the possibility of hope. Throughout the Breath of Fire series, every incarnation of Nina has been a joyful and charismatic winged girl who spurs Ryu toward his destinies. In Dragon Quarter, Ryu has a voice and Nina has been robbed of hers, one of many side-effects of the experiments that have mutilated her body. Nina bears the physical evidence of the torturous experiments, though none are so obvious as the pair of translucent crimson wings on her back, purposely inverted. What appears as wings are actually a pair of genetically-modified organs that function as exterior companions to her lungs—this Nina is a filtration experiment that can breathe in the toxic pollutants that are killing the underground populace. After taking her to the Trinity resistance with Lin and learning the truth of their theater, Ryu's conflict is erased. There is only one hope, and that is making their way to the surface.

We will never know what happens after their ascension. While the game has a somewhat hopeful ending, it cuts the narrative short on purpose. The player is granted just enough imagery to fan the flames of imagination, and optimistic gamers might fill in the blanks for the trio. This is the most fitting end to their story, hoping that after such an intense struggle there might be enough good in the world to create a new society, or perhaps join an escaped group that realized the truth hundreds of years ago. Like a living body breaking free of a time capsule, they must all face one final terrible truth together and come to terms with stark reality. Oftentimes the only way to break free of an imposed limit is to realize the limit exists at all.

The Sky Is Yours

There is a cryptic perfection to Dragon Quarter's storytelling that has, in the years since, been utilized by games like NieR, The World Ends With You, Dark Souls, or Hades. Its repetition builds something grandiose against a deceptively small scope. Everything within Dragon Quarter feels claustrophobic and compact—we are given so little information about the game's lore, even through its re-contextualized Scenario Overlay System. It is not a race to the end—you play, again and again, uncovering, threading your way through an archaeology of unknown passages and rooms, praying that the next area contains a shop, a save point, a cutscene. Subsequent play-throughs can feel just as punishing, demanding a level of thoughtful strategy for every fight. We are ascending bit by bit, hoping for the nearness of a calming reward.

In Shadow of the Colossus, there's a gameplay element that's completely divorced from direction, necessity, or reward. Should you consume the white tails of enough black lizards and increase Wander's stamina, you can attempt to climb the tower atop the Shrine of Worship. It's a rough climb and takes several minutes. Even with the proper amount of stamina, it's possible to fail the ascension, dropping Wander to his death. Should you succeed in the climb and make it to the top, you will find a garden. What's interesting about this piece of side content in Shadow of the Colossus is that it serves no observable benefit; making it all the way up to the garden rewards you with only the garden itself. There are fruits on the trees in this garden, but unlike the others, throughout the game that bolster Wander's health bar, these permanently decrease it. While there is a scene near the end of the game showing otherwise unseen animals populating the garden, none of them can be found upon Wander's visit.

The director of Shadow of the Colossus, Fumito Ueda, said: "The fruit in the ancient land was set to get you closer to non-human existence. The (secret garden's) fruit was set to return you to a human one." (From a now non-existent 1Up interview)

As with Shadow of the Colossus, Dragon Quarter's ultimate reward feels small. In an era where RPGs were becoming more and more like film, Dragon Quarter pulls back. When it comes time to finally view the surface, the game instead asks you to look back the way you came and consider the journey. It's not only in the cyclical demand of playing the game again to uncover new context, but to think on the accomplishment itself. It's evocative of Final Fantasy VI's short and bittersweet ending, a snapshot of a positive future only left to player imagination.

Game Over, Restart

It's fair to say that I reached an obsession while playing Dragon Quarter. This entry in the Breath of Fire series feels like more than a hidden gem, it feels like a piece of video game literature that has been robbed from us and locked away. Shocking modernity aside, Dragon Quarter's attempts at circumventing the JRPG should be applauded, both in the story and in gameplay. It's reflective of a living society, one that is slipping more and more into the stark images of this buried tower. The pilgrimage of Ryu, Lin, and Nina resonates because it's one built on unending hope. You take the next step because you can only ever move forward, you push on through the door hoping for the light.

This is a game about status, courage, and comradery. Where it abandons convention it enforces creativity, and there is plenty here to love. While its minimalist approach to both storytelling and progress might be too off-putting or difficult for some players, I urge you to play through the game and appraise it on your own. When it shines, Dragon Quarter feels like the best a JRPG can offer, a concise and strategic entry in a series that wanted to burst through its skin and be something heightened.

Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter deserves more than a second chance and a new audience, it deserves an apology. It has become a personal favorite, an example of video games that swing hard for the fences and take chances even within the safety of a known series. Dragon Quarter saw our future in video games, in society, in genre, in story—the dragon that's waiting inside all of us is the one we push down and ignore. Perhaps there is some era where the dust is blown off and the game is celebrated for what it is, but until then it will be forever waiting beneath the ground.