Bravely Default as Ergodic Literature

Will you be brave enough to unravel the story?

Every game that requires mechanical interaction is an obstacle course. Said obstacles vary by goal, relatedness, and even aesthetic information being conveyed, but it’s a natural part of the art form to require some kind of effort by its audience to be able to exist.

The definition of Ergodic comes from the Greek words “ergon” and “hodos”, meaning “work” and “path” respectively. Espen J. Aerseth, in his 1997 book Cybertext used (and coined!) this term to refer to narratives (not necessarily books) that require some effort to develop on the reader/player/consumer’s side. You need to “work” for the “path” to unfold, implying some friction between the text and the reader. His words:

“A reader, however strongly engaged in the unfolding of a narrative, is powerless. Like a spectator at a soccer game, he may speculate, conjecture, extrapolate, even shout abuse, but he is not a player. Like a passenger on a train, he can study and interpret the shifting landscape, he may rest his eyes wherever he pleases, even release the emergency brake and step off, but he is not free to move the tracks in a different direction. He cannot have the player's pleasure of influence: "Let's see what happens when I do this." The reader's pleasure is the pleasure of the voyeur. Safe, but impotent. The cybertext reader, on the other hand, is not safe, and therefore, it can be argued, she is not a reader. The cybertext puts its would-be reader at risk: the risk of rejection. The effort and energy demanded by the cybertext of its reader raise the stakes of interpretation to those of intervention. Trying to know a cybertext is an investment of personal improvisation that can result in either intimacy or failure.” - Espen J. Aerseth - Cybertext: Perspectives in Ergodic Literature

What the author argues here is that in certain texts, the way we navigate the words goes beyond reading - i.e. choose-your-own-adventure books, deeper experiments like Mark Z. Danielewski’s House of Leaves (a book that asks you to go back and forth between pages and footnotes, turning it upside down and sideways, telling two different stories simultaneously with different fonts, creating a labyrinthine experience emulating its own actual narrative about a House with an ever-changing labyrinth inside one of its rooms) or the Chinese divination tool I Ching. Espen then goes on slowly unfolding his actual point: computer games, using a variety of examples.

The author would develop his own career in games research, so I do not claim the “games are Ergodic in nature” argument as my own — it was his idea from the start, creating a basis for his own further studies down the line. What I postulate here is to go a little further: since the original argument was for a practice that challenged the expected norms of Reading (the challenge, then, being Playing), the Ergodic nature of an interactive medium needs to require another dimension of Playing, or Interacting. When talking about adventure games, Espen argues that the way it falls under the thesis is by their possibility of having different “narrative points” blossoming under the player’s agency — not just the possibility of doing things out of order, but having spontaneously new threads flourishing by interactivity — something that has been deeply explored by the emergent narrative conversation topic.

“This mutual construction of fiction as an interactive object, however, is intrinsic to narrative literature but is less so to forms such as poetry and drama, which are not usually thought of as fiction. (...) Such interactive fiction as an adventure game is even less fictive than a staged drama, since the user can explore the simulated world and establish causal relationships between the encountered objects in a way denied to the readers of Moby Dick or the audience of Ghosts. The adventure game user cannot rely on imagination (and previous experience) alone but must deduce the nonfictive laws of the simulated world by trial and error in order to complete the game. And a fiction that must be tested to be consumed is no longer a pure fiction; it is a construction of a different kind. (...) Be that as it may, interactive fiction is perhaps best understood as a fiction: the fiction of interactivity.” - Espen J. Aerseth - Cybertext: Perspectives in Ergodic Literature

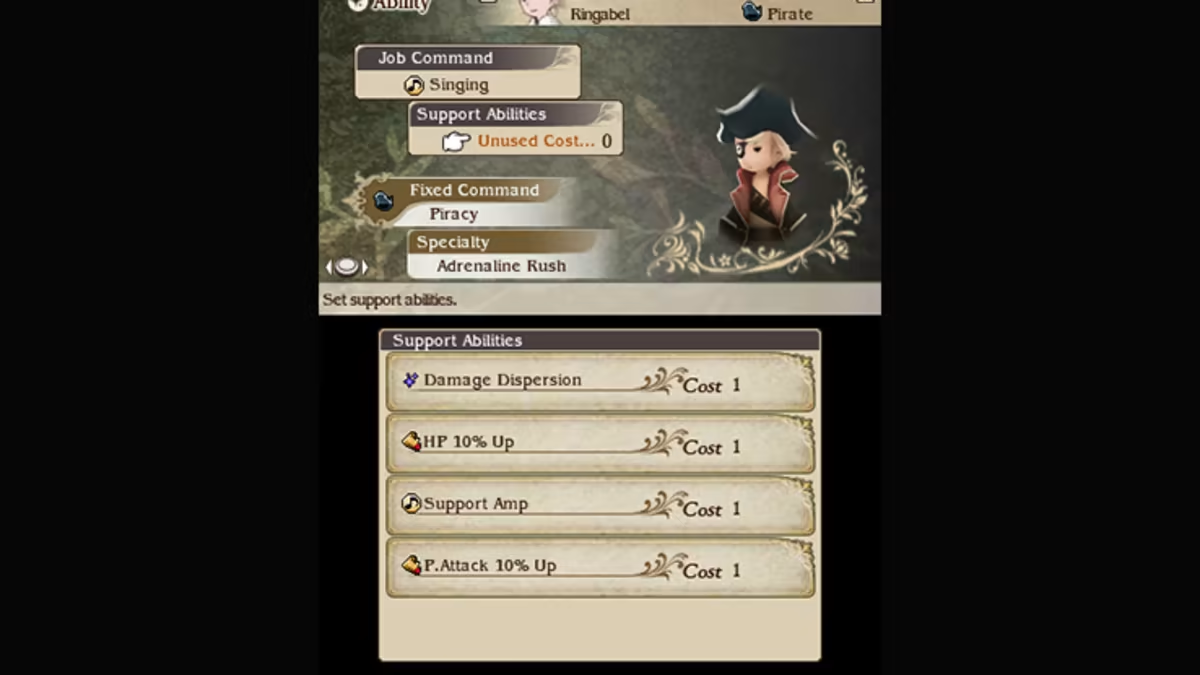

It's expected of games to challenge us mechanically, spatially, and strategically. An excellent example and the one we will use to study these ideas is the 2012 JRPG from Square Enix, Bravely Default. The game gives us a lot of control, providing a deep customizable system where you can mix and match characteristics from a variety of more than twenty classes among four characters. This in itself gives us some control over the harshness or kindness of its world: apart from difficulty levels, our combination of classes can also make the game harder or easier, depending both on the raw numbers provided by the game and also our own affinity to specific jobs or combinations. Going even further, you can also tweak factors such as encounter rate and quantity of money and experience per battle, providing different dynamics of play.

None of that quite edges out the ethos of the original Ergodic literature, however, as, although those are all welcome additions and fruitful examples, they can all fall under the expectations of the medium. The challenge comes from the team’s willingness to challenge a part of the public with preconceived notions of the historical position of the Japanese role-playing game.

The Bravely Default team has set out to make a “classical Japanese role-playing game”, deliberately taking cues from the Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, and SaGa games — three branches that are also under the Square Enix banner. The same team even worked on Final Fantasy: The 4 Heroes of Light previously; suffice to say, they were able to grasp the essence of the JRPG genre in more ways than just having an interest in it. The game was also marketed as a follow-up to those classics, actively capitalizing on the public’s misaimed eagerness for a “return to form”. Bravely's subtitle, Where The Fairy Flies (or just Flying Fairy in Japan) was also a nod to the Final Fantasy brand and its “FF” moniker, among numerous other direct references (job classes, crystal theology, magic names, etc). Although with originality, the game is extremely hermetic in the way it handles those expectations. It's a game made by fans of other specific games, for fans of those games, under a very adjacent brand. Its own mythos and fiction are taken straight out of those other experiences - both pointing them out as references and just wearing them as their own with no further explanation. More than an homage, Bravely Default tries to make said things its own, cannibalizing the interest of a group as the best possible meal.

With self-awareness regarding the genre itself, there is also awareness about the lexicon of game creation referring to the genre. There are common words and general conversation topics that are, on a meta-level, also a part of game creation to appeal to a specific part of a consumer group. Words such as “backtracking”, “padding”, “repetitive”, “boring”, “and slow”, have been a part of the games-as-products curation ever since its inception, with varying degrees of correctness when used. These are characteristics that received noun-like status, used as signs of something being good or bad on their own, without any sort of context or nuanced recognition of handling these characteristics. A resignification of adjectives as form, regardless of their concept.

Spoilers territory

Bravely Default challenges the general pathos of the videogame appreciation form: throughout its second half, in the way in which you can actually escape it.

After thirty or so hours of gameplay, the story reaches a climactic point: the four crystals have been awakened, something that your companion character, a fairy named Airy, has tasked your group with doing ever since the game started. Instead of it leading to a final dungeon, a reveal of how everything was a plan from the start and a way for the narrative to flow from this point onwards, or at least showing what it actually means for the world, our group of heroes wakes up in a familiar inn and everything they did amounted to nothing. The crystals are dormant again, the regions we saved when we dealt with their corrupt political leaders have the same problems again, and the world map has all of the Main and Side Quest icons in all of their orange and blue glory. The group is confused, and Airy just says that she doesn’t know what happened, so they should try doing it again.

You have more choices here than you did the first time you went through the ordeal: dungeon paths are now already open (since you went through them before), so navigating them is easier. Also, there's no clear incentive to do Side Quests again — when you first complete them, you were rewarded with new classes to play around with. Since you already have those classes now, there is no need to repeat those. You can, then, just turn random encounters off, go straight to the crystal dungeons, and defeat their bosses again, which will be easier since you're stronger than you were the first time you went through everything. If you decide to do the sidequests again, you'll realize that they actually have some new information: new dialogue, although subtle, that changes the perspective of things a bit. Nothing new mechanically, but they reward your patience with new character tidbits.

Whatever you decide to do, once you reawaken the four crystals again and go to the marked area on the map... the same thing happens. Same Inn, same confusion, same Airy not knowing what happened and asking the group to do it all over again. Same icons, dungeons, monsters, Main Quests, and Side Quests.

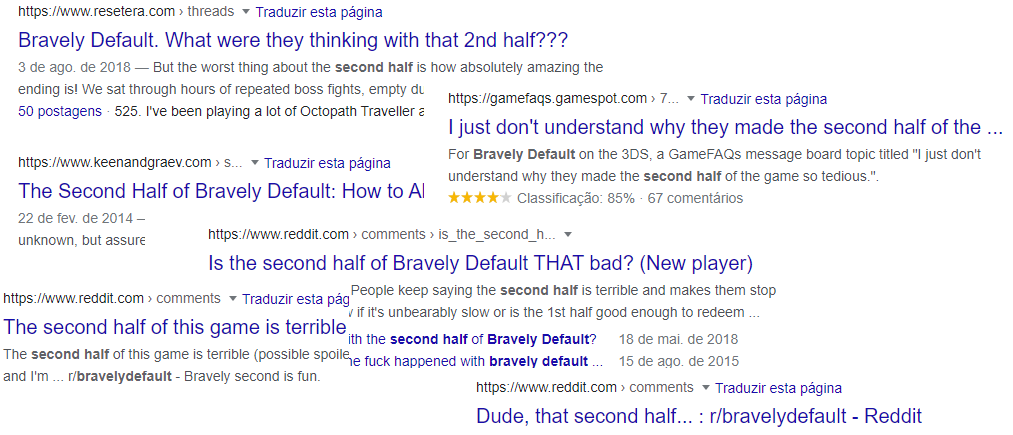

This is where any contention about the game in mainstream media and game circles resides. Although Bravely Default was well-received, the "but..." always comes: the second half is padded. It wasn't executed well. It ruined the game. It was awful.

During this loop, you already saw some scenes questioning the nature of the characters, but what seals the deal is that if you close the game or die and try to load it again, the title screen will change. The "FF" flashes red and vanishes, leaving us with Airy Lies (or Lying Airy, in the Japanese version). That's exactly when the game assumes its own identity instead of being an amalgamation of known tropes and references. Final Fantasy is gone, you have been duped, and you are doing it all over again because that's what you wanted when you longed for the same games you have already played a hundred times over.

In-universe, we finally realize how pushy Airy has been for us to reawaken those crystals. Every time the characters reach one of them, we need to press the X button repeatedly while one of the main characters suffers to take the crystal out of its dormancy, but the fairy is also very assertive (and even violent) if we keep pressing the button longer than she wants us to. It's finally clear what the player must do: disobey Airy. The player needs to keep pressing the button after she asks them to stop. It's the knee-jerk reaction to being made a fool of: anger, vengeance, defiance. The thing is, this is not where the post-Ergodic view frame comes from. Wanting to defy Airy after being misled is what you are expected to do.

Games are puzzles that only the player has the pieces to solve. The missing piece was the information that Airy is lying, that she is evil and she has unknown plans. You have been following her whims, and now that the characters are starting to doubt her, you start doubting her too. On a meta-level, the game wants you to do it. It has called her a liar in a part of the world's structure which the characters themselves don't even have access to: the title screen! Understanding your importance in that world and seeing that you have a way of breaking that cycle in a game is how you bestow divination upon the beings living there.

You can, subsequently, just keep pressing the X button when Airy tells you to stop, which will lead to a series of boss fights and the ending of the game. The mythology is explained in what can be seen as a satisfying way and the player can feel better about not needing to repeat the cycle again. It works as a way to have a clearly structured story, too: you saw the twist, you defeated the boss, some things were left hanging but they are over, and you were able to finish the game by using your intelligence as a player — choosing the most suitable classes, maybe grinding a little, and seeing four digits jump out of the final boss every time you attack.

The hard path, however, is when you actually decide to keep doing what Airy is asking you to. Instead of trying to jump the gun and outsmart the game as soon as you are able to, you wait. You use that knowledge you acquired about the lies of Airy and do the opposite of what's expected, maybe waiting for more information that would come from a different source than the fiction itself. If the player decides to courageously follow the way that he knows is wrong, some things slowly change. There are fewer Side Quest icons now, and when you explore them the story they tell is different. The bosses that you already defeated three times are now harder. Now those bosses know what the player wants: a challenge. The player is challenging the game, and the game is challenging the player back. The enemies start using optimal class compositions, calling friends, and throwing curveballs during fights. The player characters keep asking if the player is doing the right thing. They ask Airy uncomfortable questions. The game still demands the player to just break the crystal and be done with it.

Another loop ends, and the familiar Inn pops up again. The characters act confused, as they already know what is happening, but whatever forces control them doesn't let them break free. You need to complete the loop one more time. Do the Side Quests — now even harder than they were — again. Walk through the same paths, and press X the number of times Airy asks you to again. If you are able to complete it once more, you'll be truly free. Then the characters will understand why they needed to do it five times. If the player gathers the clues, reads the in-game books, and pays attention to the details, they'll realize that Airy is not the problem: she's working for someone, and the only way to reach that someone is by exercising patience, understanding of the mechanics, and their own resistance to repetitiveness. The player needs to swallow their pride, reevaluate the value of their time, and trust their own gut instead of the story that he has been playing. Do the expected thing in the most unexpected way. The player needs to bravely default.

As the medium of games has grown, the meta-fiction aspects of it also became bigger and bigger. Nowadays, games that don't have subversions are seen as rare, or as "comfort food". The JRPG genre has been accused of many things: too much, too little, too simple, too convoluted, too safe, and too different; and the team behind Bravely Default was well aware of those criticisms. Instead of trying to appeal to one side or the other, they were able to craft a tale of courage that not only creates a difficult path for its characters, but for the player's own knowledge of themselves.

During the actual final battle — when you do the loop one more time and meet the actual big bad — the sky of the fight is a chaotic mess of colors and lightning. Sometimes, during flashes of light and expressionistic hues twirling around, your own face appears as part of the cosmos (if your 3DS camera is working). You are an integral part of the fiction. You are not only the embodiment of determinism that deals with all video-game characters: you are there. Your will has reached them. Your decisions about what attack to use, what class to wear, and whether random encounters should be on or off, are all truths in that world.

Messages can be conveyed in a myriad of ways. Bringing discomfort, boredom, frustration (delightfully explored in this essay by Bennet Foddy), anger, or other unpleasant feelings to the table are also valid forms of expression, especially if we engage with them with an open mind and heart, in safe environments. Being able to exert our agency over fictional worlds can make them bleed back into us, overwhelm us, and sometimes that's exactly what we need to learn a lesson.