Baroque - Sin and Suffering

Baroque's timeless iterations deliver an unparalleled roguelike experience

It's rare when I have to admit that I don't know exactly what a game wants from me.

Too often video games trip over themselves to offer understanding on a platter. Tutorials last hours upon hours, pop-up instructions smear a busy screen, and reductive gameplay mires a widespread section of gaming that feels afraid of its audience. Commercial mainstream gaming has a singular goal, cleaved for you personally: it's essential that you understand everything immediately, imagination and discovery be damned.

Baroque humbled me. It made me yearn for something I never had, something my dim consciousness was barely aware it wanted. Baroque, like so many games that find me years and decades later, has become a favorite on the grounds of its otherness. It's an experience like no other, a quintessential horror RPG.

In the years before the widespread popularity of the roguelike (and roguelite subset) genre, the Mystery Dungeon franchise by Spike Chunsoft dared to imagine a different breed of RPG more heavily reliant on dungeon crawling that redefined the linearity of progress. While many of us are aware of the Pokemon Mystery Dungeon games, Spike Chunsoft's roguelikes have included characters from Final Fantasy, Dragon Quest, and Shiren the Wanderer.

There were other games that attempted to scale the roguelike concept previous to Mystery Dungeon (such as Fatal Labyrinth and Dragon Crystal published by Sega), but the concept wasn't broadly defined until around 1993. The most grandfatherly of roguelikes date back to the text-based procedural PC RPGs of the 1970s. Spirited by the raw dungeon crawling of TTRPGs like Dungeons & Dragons, roguelikes (and roguelites) have somewhat defied rigid definitions, and cover a broad segment of gaming from indies to AAA.

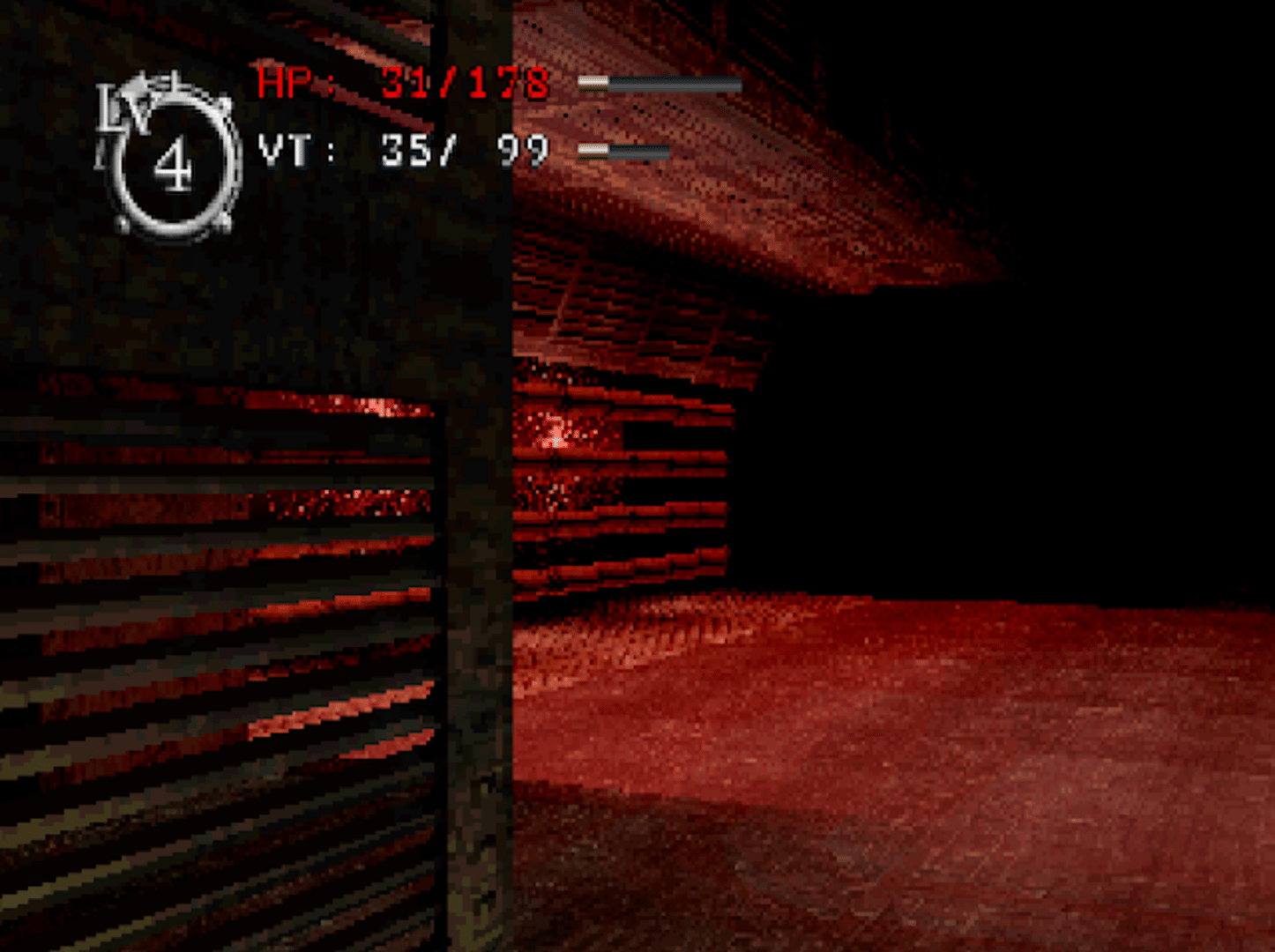

Baroque is a species of video game that aggressively defies definition. Both the original Sega Saturn/Playstation version and the remake for PS2/Wii follow similar structures, with similar ideas. Born out of the industrial punk aesthetic of the late 1980s and early 1990s, Baroque attempts to unite roguelike gameplay elements, nonlinear storytelling devices, religious and philosophical iconography, despairing post-apocalyptic settings, Dante-esque suffering, and gruesome perspectives on humanism and divinity into a single disorienting experience expertly crafted for those of particular taste. It is an interactive Hieronymus Bosch painting. It's a living Nine Inch Nails song.

Directed by Kazunari Yonemitsu (the inventor of Puyo Puyo and one of the founders of Sting Entertainment), Baroque's dark and disparaging aesthetic was chiefly inspired by European cinema, particularly film noir such as Delicatessen by Jean-Pierre Jeunet. An inarguably heavy piece of vibe-based storytelling, Baroque and its supplementary storytelling elements craft an Escherian narrative of perseverance against a hopeless backdrop of despair, ruin, and misery.

"I've been using movies as examples to get the staff all on the same page. The 3 movies I've been showing are "Blade Runner", "Delicatessen", and "Cannon Town" from the omnibus film "MEMORIES". Regarding the color palette, I think games up till now have followed in the footsteps of Hollywood movies - that is to say "bright, bold, and fun". However, Baroque has a dull look, like an Eastern European or Danish film. Going further with the movie comparisons, it has a "film noir" atmosphere. Rainy nights in a rotten city. Lights shining in darkness... You could say it has the atmosphere of the near future I suppose? It's a vision of the future, streets of decomposing structures in a distorted world. That's the kind of image the world of "Baroque" has." —Kazunari Yonemitsu, Sega Saturn Magazine, August 23rd, 1996

Yonemitsu admitted in the same interview that elements of Baroque were imagined or defined by the violent eccentricities of real-world cults. Near the time of its design, the Aum Shinrikyo cult carried out the Tokyo subway sarin gas attack that killed 13 people and injured dozens more. Yonemitsu-san's brainstorming became a mixture of real-world inspiration, film, and art. There were several keywords that became paramount to Baroque's initial design, including "imprisonment," "torture," and "light and dark." Yonemitsu was inspired by phenomenology, especially the Freudian concept of investigating the unconscious self.

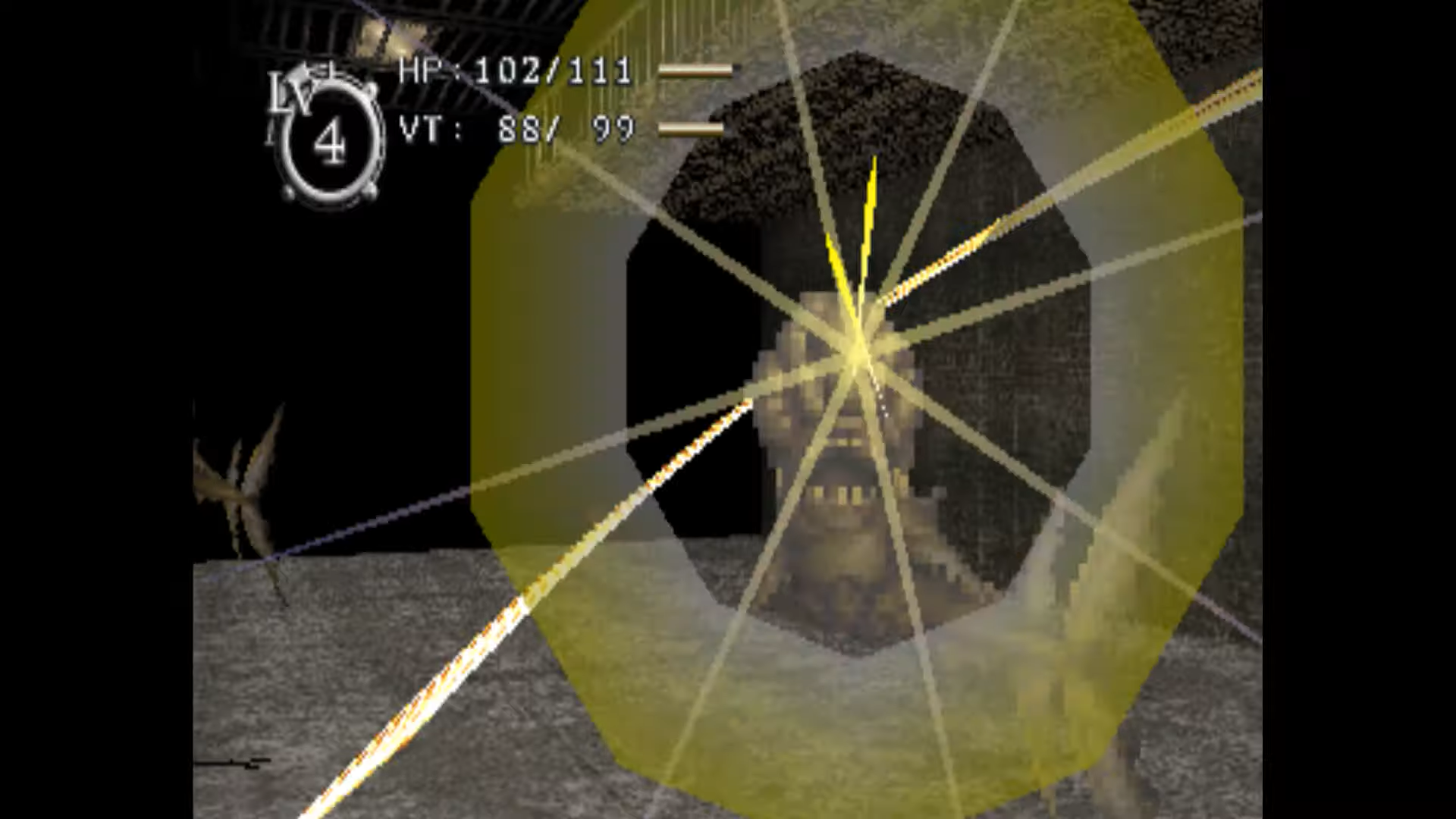

Like all great works of fiction, Baroque wasn't designed in an attempt to appeal to a certain existing audience but to define its audience outright. The PlayStation and PlayStation 2 eras often feel like lost epochs of design, where the tried and true genres of the present day were not quite fully formed. Baroque, then, sought to be a mishmash of things its creators found intentionally interesting and wanted to avoid any allusions to symmetry. Yonemitsu, when speaking with their artists about the design of the monsters, wanted to ensure that all the grotesques matched the asymmetry of their distorted world. Since the original Baroque is entirely a first-person action game, the monsters had to evoke a strength of narrative.

"That's right. The flow of the story is different from that of existing games, so it can be difficult to get through. Based on the consequences of the actions performed by the protagonist and the state of the world, the actions and feelings of the other characters will change. The story is filled with individual variables like this." —Kazunari Yonemitsu

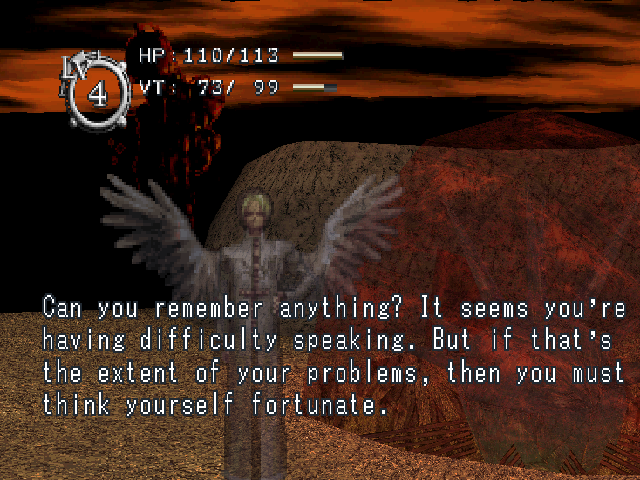

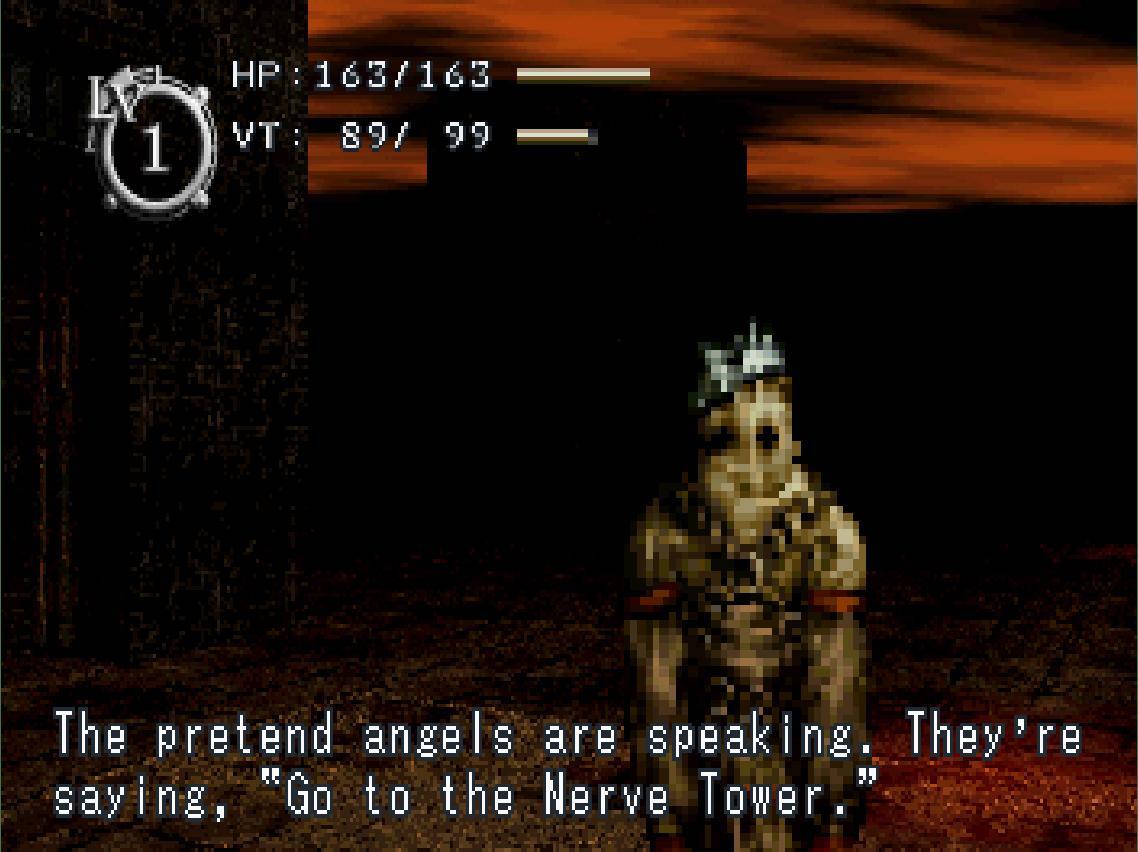

This speaks to Baroque's key component, which is its atmosphere. Atmospheric video games have fallen out of favor in lieu of cinematic aesthetics or enormous open setpieces. Like Vagrant Story, Bloodborne, Ico, or Bioshock, Baroque goes all-in on its adherence to artifice. While certain aspects of Baroque may remind players of Shin Megami Tensei, the game's dieselpunk atmosphere immediately serves a future in which humanity's worst components have flourished. The second the game begins, the player is met by a dreary rust-colored industrial landscape, the air filled with inhuman howling. Beneath the shadow of the Nerve Tower (crafted as a real-world model by Eisaku Kito, who has worked with both Mamoru Oshii and NIKE) the player is immediately struck by an aesthetic that is both unnerving and unfriendly.

In the early 2030s, a cataclysmic event will destroy much of humanity—and most of the world. What remains is a collapsed wasteland filled with Meta-Beings, the grotesques of transformed humans that have lost themselves to perverse delusions and temptations of violence. In order to redeem this world, our nameless silent protagonist must fashion himself with a powerful rifle gifted by a mysterious Archangel, and use that weapon at the bottom of the tower to kill the Absolute God.

Baroque's unusual story is delineated through repetition. While many games in the roguelike genre focus on a steady stream of slow upgrades awarded after multiple mortal cycles, Baroque utilizes this format to alter the possibilities of delivering the story. The protagonist's path toward redemption intermingles with lost characters who may or may not know about his sin—and how that sin weighs upon the realities of everyone that lives beneath the shadow of the tower.

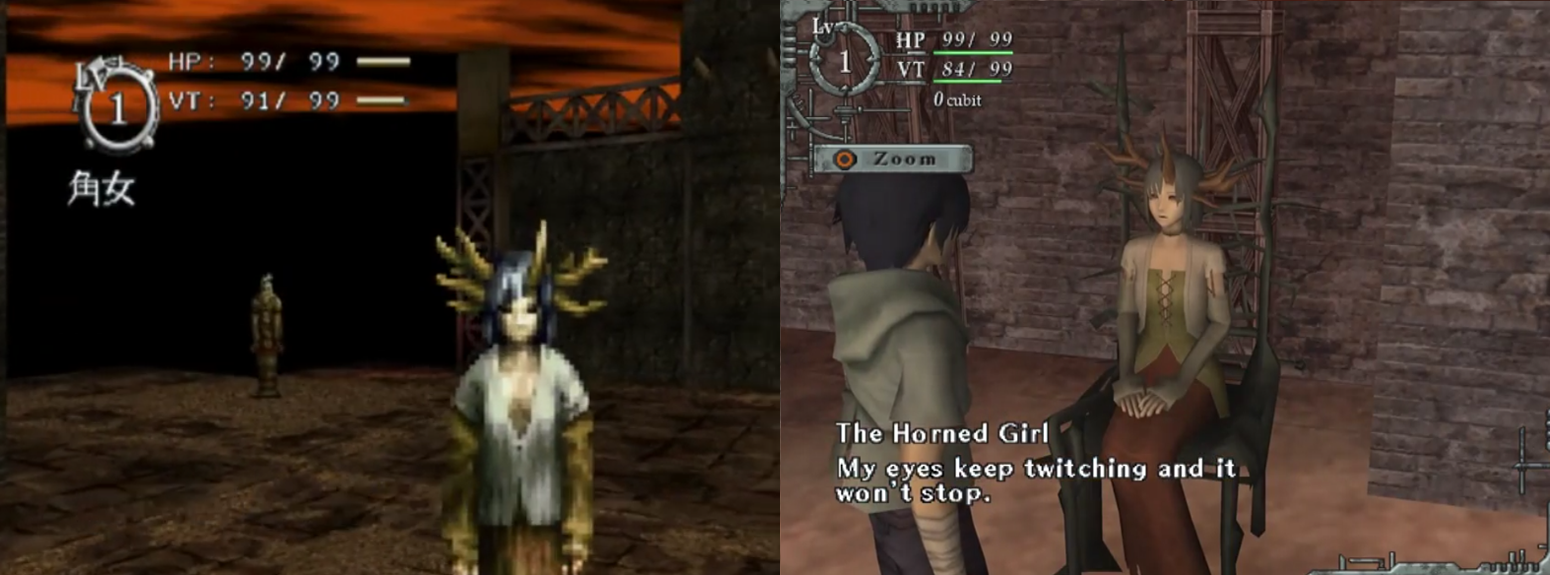

As with the incredible Breath of Fire: Dragon Quarter, the player is actually rewarded through death. While the loop of dungeon and town might start to feel monotonous, there is good reason to continue speaking with the hapless denizens in order to unearth the truth about what is going on. In adherence to the game's particular flavor of weirdness, the player must conquer the mystery with the help of characters such as the Coffin Man, the Horned Girl, Longneck, and the Sentry Angel. When exploring the labyrinthine depths of the Neuro (Nerve) Tower itself, encounters are more varied and even stranger, with characters such as the Littles, Alice, Eliza, and the Absolute God.

"If a hero plays a role in an RPG, the whole world always ends up returned to peace, but somehow I'm just not convinced. Such a simplified plot is probably possible, but I also think that this kind of story is getting old. That was the feeling behind wanting to sketch out a place inhabited by people who were not at peace. So conversely, we have healing, which is a more personal theme. I thought it would be better to have a more personal adventure, like going on an adventure to heal an injury. Through the adventure, you come to a point where you’re at peace with yourself and your surroundings, and so the world seems more peaceful as a result." —Kazunari Yonemitsu

The first "conquering" of the dungeon results in a substantial plot twist, though the player will quickly learn that there are very few material rewards. There is no upgrade or extra health to be found when you make it to the bottom of the tower. As directed by the Archangel, the player can arm themselves with the rifle and shoot God—or they can move nearer to God's presence and be gifted with a glimpse into the truth.

Every character in Baroque carries within them an aspect of the soul. These "Idea Sephirahs" or Consciousness Orbs are left behind as key elements of what they once were, living shadow remnants of beings who can carry on after death. Carrying these Consciousness Orbs and delivering them to the right characters is a key aspect of solving Baroque's mystery and moving onward with the story, but this comes with a cost. Not only is your inventory small (and constantly filled to the brim with an eclectic array of offensive and defensive items), but trinkets cannot be carried over upon death. By accessing the Sense Sphere appendages of the Absolute God, the player can toss these items toward the surface and begin to build a steadier rhythm of conquest that will continue even after death—and the inevitable reset to Level One.

Baroque's initial presentation is straightforward. After a vibrant and bizarre cinematic opening that blares industrial sludge that might make Trent Reznor blush, we are thrown into a perspective that intimates the horror before us. The base "town" beneath the oppressive tower is filled with many eclectic characters and includes a digitized Tutorial that emulates a run-through of our dungeon cycle. In order to further disorient the player, all conquests of the tower are descents, with the Absolute God resting on the final floor. After getting your bearings, the game simply tosses you into the loop: the Archangel gifts you with the rifle, tells you to kill God, and vanishes.

Loops through the Neuro Tower occur with little fanfare, though certain runs might end much faster than others. Baroque is, ultimately, an apathetic game; whether or not you survive has little bearing or importance on its overall design. It's the sort of relentless effort and experimentation you might see in something like Dark Souls, where each worthwhile reward comes from an extreme level of personal motivation. Baroque is difficult (surprisingly, I found the PlayStation 2 remake more difficult than the original), but not impossible. Anyone that chooses to play the recently published English patch of Baroque for PlayStation and Sega Saturn might be disheartened to find that the game's community is nearly as barren as the game, with the exception of The Nerve Tower collated fansite.

After reading into some of Baroque's more unusual mechanics, I resolved to the fact that my experience was going to be mostly trial and error.

"Our emphasis is on making the maps and characters realistic. We're trying to minimize elements that make it feel like a game... like not including unnatural shine produced by items." —Kazunari Yonemitsu

It's best to take your time with Baroque. I played the new English translation patch for the PlayStation version and then the PlayStation 2 remake back to back, my spirit completely corrupted by the game's tendrils. It's difficult to play a game like Baroque and not become enamored with it; not only is it the sort of game that has become a rarity, but it feels like a complete expansion of what a video game can be. In terms of design and narrative, Baroque is an example of true creative artistry in the medium, a game whose individual pieces could be endlessly critiqued but whose whole is an inarguable masterclass of creative design. Even considering the game's more frustrating components, you cannot embark on this journey without being changed.

Differences between the Saturn/Playstation versions of Baroque and the PlayStation 2/Wii remake range from inconsequential to surreal to baffling. Playing these games back to back is a trippy experience. While the PlayStation 2 remake exists in the third person, the characters, areas, and sound effects are all eerily similar. The remake seems to point toward a change in both preference and publishing acceptability. Many of the mature themes and more adult designs of the monsters are unfortunately censored for an aesthetic that reaches toward the mainstream. While the remake is a serviceable enough game and was made in-house by Sting Entertainment, its existence is somewhat confusing—so much of it is censored that it feels like a butchered and recut iteration of the original. The oppressive Giger-esque atmosphere is lessened, the heavy industrial design is given a more mainstream anime makeover, and the gameplay is unsuccessfully modernized. While the jump from Saturn to PlayStation came with its share of troubles, so many choices in the PlayStation 2 remake are detrimental to the core experience. The repetition becomes tedious, the structure convoluted.

What unites the two versions of Baroque is its story. Until recently, only the most hardcore fans had access to the original game on PlayStation and Sega Saturn—lucky Japanese fans got to enjoy a re-release for the Nintendo Switch back in 2020. Baroque's remake was released by Atlus and localized for Western audiences, but until last year there was no fully translated English version of the original game. This experience and its comparisons are owed to hard-working fans that have made an English patch available for both PlayStation and Saturn versions (Google it), an example of true game preservation that we rarely see from actual studios. Baroque is the sort of game that, despite its flaws and hiccups, garners extremely loyal fans because of its stark originality.

Baroque's narrative requires considerable patience from the player, not to mention a style of trial-and-error that feels purposefully obtuse. A religious group calling themselves the Order of Malkuth discovers the return of the Absolute God. With the return of this God were the Consciousness Orbs or Sense Spheres, living appendages of the Absolute God that serve to compress reality. The Order of Malkuth aimed to learn more about God and so began a series of experiments that resulted in distortions of reality. One of the researchers—the man who would become the Archangel—was driven mad while devising a system that would allow humanity to stream their own information directly to the Absolute God. With every attempt by the Archangel to circumvent God, the world was infected with more of its sensory organs.

Those entities turned mad by the Archangel's efforts were deemed Baroques. A world of control was built out of the Archangel's failures, with fake angels designed by his hand. These fake angels could not withstand the degree of their own delusions, and so the Archangel had to exploit his underlings and turn the entire Order of Malkuth against the Absolute God. In order to do away with God completely, the Archangel designed living bullets called Littles: cherubs of intense psychological and material pain that were strong enough to infect and erase a God. By fixing these living bullets into an Angelic Rifle, it was theoretically possible to completely kill the divine.

As the world continued to careen wildly into distortion, the Archangel took advantage of God's increasing delusions and resistance to pain. The cycle of grotesques and Baroques quickened from the use of the Archangel's living Tarot deck, a system that blinded the Absolute God from living reality and made the creation of Baroques and grotesques more plentiful. As the surviving public was tormented by mad beasts they retreated into the comforts of their delusions, which created more Baroques and in turn more monsters. The Koriel—a rebellion born from the Archangel's resistance—discovered the existence of God's recorded screams, the Tarantella Melody, and were freed from the Archangel's cycle of conditioning.

In a wild attempt to thwart the increasingly distorted world and resist the plans of the Archangel, the Koriel devised their own scientific plan called Dabar Fusion. By uniting one of their own members with the Absolute God, they could grant God the ability to communicate directly with humans and circumvent the control of the Archangel. The Koriel selected a pair of conjoined twins that shared a heart; by killing one of the twins and only allowing the other to live, they could manifest a scenario in which the aggrieved survivor would be the perfect candidate to unite with the Absolute God.

In an effort to stop the Koriel, the Archangel decides to tear the candidate from God in the middle of the Dabar Fusion. This massive anguish created a distortion beyond any the Earth had felt, a cataclysm called the Great Heat Wave that was born out of God's screaming sensory organs. This extinction event transformed the planet into a wasteland, and any non-grotesques who survived found themselves unceremoniously fused with monsters. Water became stagnant and toxic, data became corrupted, food became rotten and unedible. During the cataclysm, the Archangel's body was speared upon a Sense Sphere within the Nerve Tower, and he could only continue his work by projecting images of himself to his followers. Eternally preserved, the Archangel realized that he could salvage the Koriel's created entity and use it in his plan against God.

The player character—an entity only once known as Number 12—was infinitely cloned by the Archangel and placed into service. Each clone's memory was wiped of the Koriels, of the Dabar Fusion, everything except for their survivors' guilt and drive toward the Absolute God. As Baroque begins, the Archangel's projection tasks the clone with the destruction of God at the bottom of the Nerve Tower and hands him the Angelic Rifle. Progression only occurs when the clones of Number 12 can come to terms with their past and face their survivor's guilt. Guided by demi-divinities of God named Eliza and Alice, Number 12 must repeat his descent into the Tower over and over again until the truth is achieved.

Truth, however, is not always kindness. Eventually, Number 12 learns that the destroyed world is God's original plan and that God has no desire to create anything beyond this existence. The desire to purify and heal is, in itself, an aspect of the Baroque—a delusion of being. Baroques are a necessity of existence, they are the coping mechanism by which humanity can weather the insanity that comes with beholding God's plan. In order to cope with reality at all, the world must be distorted. Life—and all of existence—is a twisted amalgamation of false perceptions.

The Nerve Tower exists forever as a permanent fixture of the twisted aberrations of the Absolute God. The drive to unite with God, the fight toward healing and balance and unity, is the purpose of this life. The world continues forever as its wheel, a profane gesture that manufactures the illusion of paradise.

Baroque's mythology is evocative of both Western and Eastern religions, with the cycle of death and rebirth (an everyday staple in roguelikes) mirroring the Wheel of Samsara in Buddhism and Hinduism. While Baroque's ultimate ending might feel disappointing to those looking for a succinct, happy resolution, this earned repetition can be seen as ultimately virtuous. Baroque is not the sort of game you sit down and power through in a weekend; even with a guide, discovering just how to reach its final levels and merge with God can be frustrating and tedious. Baroque, in all its versions, is experiential.

While Baroque uses standard mythological and religious terms such as "God" or "Angel" to define its inhabitants, its internal lore is far more complex than ascribing it as strictly representative of faith. Whether by nature of interests or simply to deter comparisons to belief, the religious components in Baroque are so unusual that they feel more like a stand-in for the player's own experiences. Enough of Baroque can be taken as a metaphor for both human and divine hubris; the destructive event in Baroque, like so many extinction events in video games, is as much climate change as it is a weaponized catastrophe. The end of the game and its appeal to succumbing to the inevitable might be taken as dour, or liberating. Baroque's poetic reading might infer that a miserable existence is better than no existence at all.

In many ways, Baroque feels like the opposite of a lost game. While it's more difficult to access in America than in Japan, the English patches have granted it a new lease on life. Fandom, in some cases, can be the critical component of resurrecting games. Baroque feels like a microcosm of what it's designed around, a meta-narrative in which awareness of the game crafts the possibility of a new universe. Ardent fans have provided extensive further reading for those who have been transfixed by the game as I have, but reading about Baroque is not enough. If it's possible for you to experience the game (especially its recent Saturn and PlayStation translations), you might find your perception of gaming expanded, or at least be granted a new bizarre favorite.

"...how much the world changes, so on and so forth is up to you." —Kazunari Yonemitsu