Are Golden Endings Always the Right Path?

Sometimes an ambiguous ending is more satisfying than a triumphant one.

One thing which makes video games unique is their ability to tell stories with branching narratives. This is something that isn’t possible using other mediums, outside of experimental choose-your-own adventure stories like Black Mirror: Bandersnatch and The Warlock of Firetop Mountain. The interactive nature of video games makes it possible for them to have multiple different endings depending on the path the player takes through the story. This means that players can get endings tailored to their own experience.

Several games choose to have one “golden” or “true” ending, a conclusive denouement that wraps everything up decisively in a way that the other endings offered by the game do not. Golden endings can sometimes be used marvelously to reward players when their actions align with the themes of a game’s story. Undertale’s golden ending ties beautifully into its message of non-violently resolving conflict and rewards players who have been practising what the game is preaching by refusing to kill any monsters.

Similarly, Fable III uses its golden ending to provide a refreshing breath of moral nuance in a series otherwise infamous for the simplicity of its alignment system. In Fable III, the player is a Monarch who desperately needs to raise money to protect their kingdom from an incoming threat. You can rake in cash hand over fist by cruelly extorting your subjects. Staying on the moral high ground, meanwhile, either reaps no monetary reward or is actively costly. Players earn the game’s best ending by managing the difficult task of raising the money they need without compromising their morality and inflicting cruelty upon their people. Fable III argues that evil is easy, and that truly making the world a better place requires those in power to make personal sacrifices rather than expecting those beneath them to suffer on their behalf.

The decision to include a golden ending in a game is an important choice in itself. It isn’t always the right decision to simply shove a golden ending into any game with a branching story. When poorly executed a story with a golden ending no longer truly has multiple endings, it simply has one actual ending surrounded by several abortive false ones.

To compare how golden endings enhance the experience, let's look at games that included them in a way that damaged the story they were trying to tell.

Fire Emblem Fates

Fire Emblem Fates was released worldwide in 2016 to a broadly positive reception from critics, although it proved to be contentious among series fans. Although the plot of the game is a frequent subject of mockery on Reddit, its central premise is highly compelling. The protagonist, Corrin, is a child of two worlds. Their mother is the Queen of Hoshido, an idyllic and tranquil land based upon feudal Japan. As a baby Corrin was stolen from their homeland and raised in the neighboring Kingdom of Nohr, a more violent realm inspired by medieval Europe. When Nohr invades Hoshido, Corrin has to decide whether they should attack their homeland alongside their foster family or defect and defend their birthplace.

This is a very strong concept and confronts the player with a hugely difficult decision. Your most loyal allies in one of the game’s paths become your most bitter enemies in the other, adding pathos to subsequent playthroughs. Whichever side is chosen Corrin will have regrets and both paths have bittersweet endings. Whether Nohr or Hoshido ends up winning the war, their victory comes at the expense of brutalising their rival and inflicting misery upon a cast of sympathetic characters. This is a fantastic way to structure a narrative, with a single significant split dividing it down the middle.

Unfortunately, the strong premise of Fire Emblem Fates is undermined by the existence of the game’s third path. Fire Emblem Fates: Birthright follows the story of Hoshido and Fire Emblem Fates: Conquest is focused on Nohr. The third path, Fire Emblem Fates: Revelation, brings both kingdoms together and secures a happy ending for all sides. This fundamentally invalidates both of the game’s other paths and the 20+ hours of gameplay they each contain. What’s the point of offering a heart-wrenching decision between the happiness of two rival nations, when it is perfectly possible to save both? What’s the point of a storyline based around making a difficult choice when that choice can be kicked to the side and ignored?

This happy ending offered by Fire Emblem Fates: Revelation is also not tied to the player’s actions. Unlike the examples of Fable III and Undertale listed above where the best ending is a reward for players who engage with the game’s themes and make the correct choices, Fire Emblem Fates: Revelation is DLC. Fire Emblem Fate’s best route is bought, rather than earned. Accessing it does not require players to thoughtfully navigate the game, it only needs them to fork over £15.

The closure of the Nintendo E-shop means that Fire Emblem Fates: Revelation is now forever unavailable for players who have not already purchased it. While an unearned golden ending is frustrating, a completely unattainable one is worse. Both Conquest and Birthright contain scenes that hint at the existence of the game’s third path. These brief snippets of dialogue were previously implicit advertisements for the game’s DLC. They still exist, but, they now foreshadow nothing except the vacant hole left at the core of Fire Emblem Fates as a third of its content has been sealed away.

Triangle Strategy

Triangle Strategy is a 2022 Strategy RPG with ambitious storytelling objectives. The game features a branching narrative that is based on its unique morality system. Many games have alignment systems based on the principles of good and evil, or sometimes order and chaos. Triangle Strategy tries something new and invents a moral system based on three different convictions: morality, utility, and liberty.

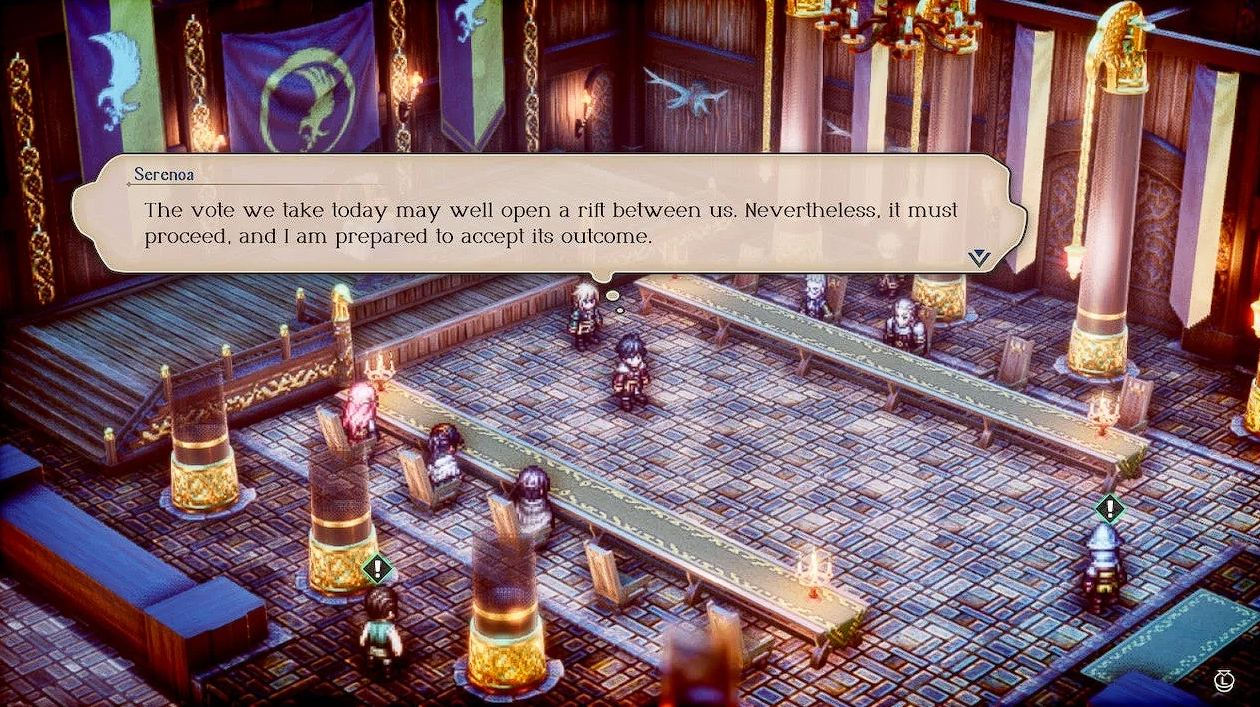

At pivotal moments, the game’s protagonists gather and vote on what their next course of action should be, with each of the outcomes relating to one of the three convictions. You might make a utilitarian decision and surrender your friend as a hostage to the enemy, subordinating their well-being for the safety of the group as a whole. You might make a moral choice and refuse to give them up, knowing that you’re doing the right thing despite the difficulty this causes. There’s also the principle of liberty which emphasise independence and freedom.

As the game goes on, the characters become increasingly ideologically divided. This comes to a head in the late game as the party finally fractures and splits. In chapter 17 the game’s final, and most important choice, is made. Each of the three convictions has its own endgame, but opting into any one of these ending routes will forever alienate one of your allies who will abandon your cause. This is a very dramatic story beat and the emotional climax of the entire narrative. Much is made of this moment in promotional material for the game. All of the gameplay footage in the first 40 seconds of one of the game’s trailers comes from this route split moment.

Once the final choice has been made, the player is locked into the ending corresponding to their chosen conviction. Both the player characters and the world they inhabit are left radically transformed in each of the three endings. None of the three paths is absolutely right, and none of them is absolutely wrong. It is up to the player to determine whether they feel they made the right choice, or whether the bad outweighs the good in the new society they have created.

Unfortunately, all of this nuance and ambiguity is damaged by Triangle Strategy’s decision to include a golden ending. Players who navigate a particular path through the story can ignore the three convictions and take a fourth option which results in a much better outcome. While this golden ending is not entirely without merit, it simply lacks the weight of the other endings. The idea that the cast needs to move past their ideological differences in order to fully grasp the truth is interesting, but the game doesn’t fully engage with the ramifications of this idea. The game presents this compromise as an unambiguous good, but is this really the case? There’s an argument to be made that having everyone dispassionately set aside their beliefs in the interest of the greater good is not necessarily positive or desirable. Since this decision leads to the game’s best ending, it is not critically examined in the same way the other three choices are.

The path to the golden ending is also somewhat arbitrary and unclear. The player has to make a series of decisions throughout the story to get there which are not readily apparent without relying on a guide. For example, the player needs to refuse to confront a contraband smuggler because this happens to result in them meeting someone whose help is essential to get the golden ending. The worst feature of Triangle Strategy’s golden ending, however, is that it renders the three conviction endings pointless. There isn’t really a point in discussing the merits and flaws of the worlds these three endings create when a utopia exists alongside them that puts them all to shame.

Warhammer 40,000 Dawn of War II: Chaos Rising

Warhammer 40,000 Dawn of War II was released in 2009. Combining Real Time Strategy and RPG elements, it told a compelling if uncomplicated story of ultra-macho spacemen fighting off a swarm of ravenous alien parasites. The game’s first expansion, Chaos Rising, was released a year later. Chaos Rising aimed to tell a more complex tale than the base game and to work in a branching narrative, even adding a new gameplay system, known as corruption, to accommodate this goal.

The Chaos Gods are some of the most malevolent entities in the Warhammer 40,000 universe, which is saying a lot because this is a setting where essentially every single faction revels in inflicting as much pointless cruelty as possible. Chaos Rising’s corruption system represents the grip that the Chaos gods hold over the player character and their fellow burly space soldiers. Every character in the game has a corruption meter. This meter is raised by performing evil actions, using equipment tainted by chaos, or using chaos-aligned abilities. This means that players attempting to avoid gaining corruption have a difficult challenge ahead of them, as they are forbidden from using all of the skills and items in their arsenal.

It is revealed early on in the story that one of the characters in the player’s squad is a traitor. Although the identity of the traitor is not known, their presence is keenly felt as it is clear that someone is leaking information to the enemy.

During the game's penultimate chapter, the traitor reveals themselves, and their identity is based on the corruption system. The traitor is whichever member of the player’s party is the most corrupted at the endgame. All of the player’s party members have distinct motivations for betraying the rest of the group. These motivations range from sympathetic to spiteful but, crucially, even though the identity of the traitor is variable their reasons always make sense and are consistent with their prior characterisation. This creates an exciting climax, as the player is forced to fight against one of their comrades. The player loses access to that character and the vital role which they fulfill permanently. If the player is invested in the traitor’s character, they are also sure to feel a gut punch as they battle their former friend.

There must always be a traitor. The idea that someone the player trusts is actively betraying them is seeded very early on, and plays a key part in creating the suspicious atmosphere of Chaos Rising’s story. This creates a problem if nobody in the party has any corruption by the time the penultimate chapter is reached. In order for its story to work in this scenario, the game outsources the role of the traitor, rather than it being a member of the party it is instead an NPC.

Martellus is a background character who provides tech support to the protagonists throughout the campaign. Martellus steps into the role of the traitor for players pursuing the golden ending. This is a functional solution, but one which is ultimately narratively unsatisfying. The revelation that one of your close friends, and a character you have been controlling throughout the entire campaign, secretly despises you is shocking. The revelation that the mechanic you sometimes hang around with is actually an evil jerk is decidedly less impactful.

The corruption system and the traitor mechanic are fantastic innovations. Broadly, Chaos Rising succeeds in its objective of weaving a mystery where the culprit can be different across multiple playthroughs. The only issue with this system is that the least interesting narrative path is provided to players aiming to unlock a golden ending by remaining pure and avoiding gaining any corruption whatsoever. Players are thus punished, rather than rewarded, for taking the hard path through the game and resisting corruption.

Conclusion

When telling a branching story, it is best to ensure that every single path you offer has its own merits and faults. Investing too much in a single route can leave the rest of the options feeling like afterthoughts.

The golden ending of Fire Emblem Fates negates the choice which lies at the heart of its story. Offering players the ability to save both Hoshido and Nohr, makes the paths that provide happiness for one or the other moot. Triangle Strategy, similarly, undermines its three alignment-based endings by presenting a fourth option that supersedes them all and renders them redundant.

Dawn of War II: Chaos Rising’s weak golden ending is less due to a desire to provide an overriding happy ending and more due to an unfortunate quirk in its narrative systems. The game works well at providing varied conclusions, however, it gives the least interesting outcome to players who take the hardest path.

When executed correctly, and placed in the right story, golden endings are great and give players who have heavily invested in a game a reward for their commitment. Importantly, however, Just because golden endings work sometimes, doesn’t mean they should be employed in every game with multiple endings. While it can be tempting to want to wrap everything up with a neat little bow, not every story needs to provide absolute and unambiguous closure.