Ancient Worlds, Part 1: Revisiting the MMOs of Yesterday

What happens to MMO communities when the industry moves on?

There is a particular genre of games that, in my eyes, stands as so unique that they can scarcely be referred to simply as games. Massively Multiplayer Online (MMO) games are not just games — they are communities and social networks that have existed since long before the term “social network” existed.

The games that we once referred to as Massively Multiplayer Online Roleplaying Games (MMORPG), and now more commonly simply as MMOs, have had a long history, almost as long as gaming itself. They evolved from what was referred to as Multi-User Dungeons (or later, Dimensions or Domains), a.k.a. MUDs. These were an evolution of earlier multiplayer games, like Mazewar, which were used to test the capabilities of prototype networks, such as ARPANET. The first MUD was, in fact, MUD1, developed by Roy Trubshaw and Richard Bartle at the University of Essex in 1978. Amazingly, you can still play MUD1 today — you just might need a little understanding of Telnet, however.

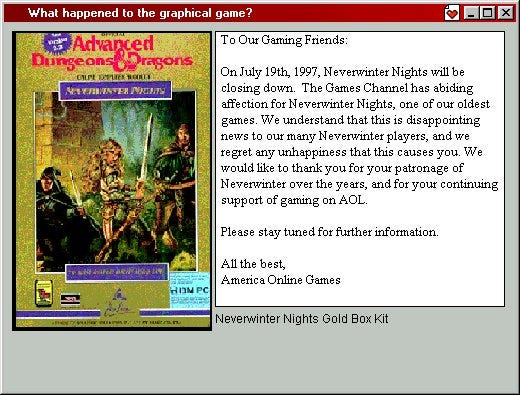

Until 1991’s Neverwinter Nights (Beyond Software — unrelated to BioWare’s 2002 RPG), MUDs were a text-based affair. You interacted with the world entirely through walls of text and sentence parsers. Beyond Software’s Neverwinter Nights could probably claim the title of being the first MMORPG, although “massive” is a relative term — getting 200 people in the same multiplayer game using 1991’s fledgling internet infrastructure (courtesy of AOL) was an absolute feat, and entirely worthy of being dubbed a “massive" online game.

It stands in stark contrast to a game like EVE Online (CCP Games, 2003), which uses a single game world for its entire player base, and hosts almost 500,000 players per day. Neverwinter Nights was an open world, but not in the way you might expect. The world was a collection of discrete areas, such as the Lost Hills, Neverwinter, and Luskan, that players would move between, rather than the true open worlds of later MMOs.

Neverwinter Nights was a watershed moment in the development of MMOs. In the early 90s, multiplayer was a concept beginning to gather steam, but much of it was restricted to local area network play between students using university networks, playing competitive FPS games like Doom. Neverwinter Nights demonstrated multiplayer on a large scale in an immense interactive world.

Development continued over the years, eventually increasing the server capacity to 500 players, however in the game’s later days, a player could end up queueing for hours to access the server due to its popularity. On top of this was the sheer cost of playing the game. Early adoption of technology is rarely a cheap decision, and internet access in the mid-1990s was no exception. The cost of playing Neverwinter Nights stood at about USD $6 per hour, and many players invested hundreds or thousands of dollars playing the game. Not exactly an approachable hobby.

Neverwinter Nights ceased operation in July 1997, despite the fact that it was still both popular and financially viable. This sent shockwaves through the game’s player base and provided the first example of what truly defines MMOs — a sense of community. After Neverwinter Nights was shut down, a large portion of the 100,000 or so players banded together in a sort of community-in-exile, forming groups in IRC and forums, and maintaining the history and legacy of Neverwinter Nights on sites like The Original Neverwinter Nights. BioWare’s 2002 CRPG Neverwinter Nights was a love letter to the original community and using the extensive modification tools and online features bundled with the game, the original Beyond Software MUD was resurrected as a fan-made modification. Neverwinter Nights: Resurrection was one of many fan-made MMOs using BioWare’s game as a base, but player-made MMOs are a topic for another day.

1996 was a huge year in the development of MMOs and is widely recognised as the year that MMOs “began”. This year saw two MMO releases supported by major studios in the Western market, and the first Asian MMO, Nexus: The Kingdom of the Winds (Nexon, 1996), in South Korea. The first of these was The Realm Online (1996), developed by Sierra On-Line. Aesthetically, The Realm Online had the appearance of a Sierra-style adventure, like a multiplayer King’s Quest. Within 12 months of release, The Realm Online already boasted 25,000 players. Widespread adoption of internet access in the late 90s started to reduce overall costs, and MMOs were no longer an extravagant expense (though they were hardly cheap).

In Asia, MMORPGs were embraced from the very start. Nexus: The Kingdom of the Winds was Asia’s first MMO and one of the first in the world, released before both Meridian 59 (Archetype Interactive, 1996) and The Realm Online. Much like Asian RPGs have developed their own distinctive style compared to Western RPGs, Asian MMOs have similarly evolved into their own unique brand of MMO.

Nexus was embraced immediately in South Korea, and unlike Western titles, featured much more focused narrative elements — something that wouldn’t appear in Western MMOs for several years. The game is now one of the longest-running MMORPGs still in existence, and in their Q2 2020 financial report, Nexon stated that there are still 300 registered Nexus players.

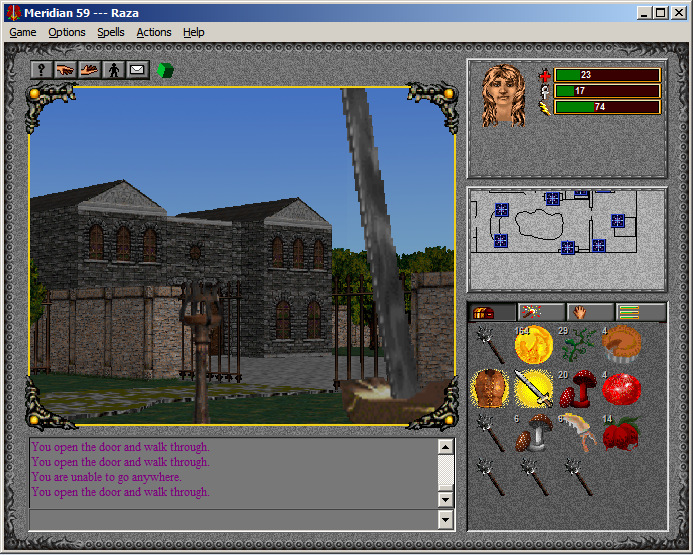

The other release from 1996 was Meridian 59, by Archetype Interactive, and published by The 3DO Company. More than any other game at the time, this was the one that most closely represented what MMOs would become. It was the first MMO, or “graphical MUD" as they were then known, to have a fully realised 3D environment, similar to 1996's The Elder Scrolls II: Daggerfall by Bethesda Softworks. It also incorporated a monthly subscription model that eventually became the industry standard.

Meridian 59’s initial response from gamers was impressive, launching with around 17,000 subscribers. It was rapidly becoming clear to the games industry that MMOs were about to be the next big thing, and the ability to live an alternate digital life captured the imagination of the dot-com generation.

Meridian 59’s dominance was short-lived — in 1997 Origin Systems released Ultima Online, a game that would send records tumbling and come to define the first generation of MMORPGs. It was during this time that the term “MMORPG” emerged, allegedly coined by Ultima series creator Richard Garriott, and it was the term that the industry embraced as a genre descriptor.

Ultima Online’s initial response wasn’t quite as enthusiastic as Meridian 59’s, but it soon began to rapidly outpace its rival. A year later, Ultima Online’s subscriber base exceeded 100,000 and peak times saw up to 20,000 players logging in at once.

There are several possible reasons for Ultima Online’s massive success. One of those is quite likely to be “second-mover advantage” that is so often seen in technology-related fields. The first-mover’s advantage is offset by the fact that they make all the first mistakes, and discover the first bugs and problems. The second-mover has the advantage of learning from the pioneer’s mistakes, and this is undoubtedly something that Origin Systems used to their took advantage.

There were other possible reasons for Ultima Online’s success. Firstly, the Ultima name was computer gaming royalty. Series creator Richard “Lord British” Garriott was one of the first RPG game developers, starting the series with Akalabeth (a.k.a. Ultima 0) in 1979. By 1997, Ultima had become one of the longest-running series in the industry’s history, having seen Ultima VIII: Pagan released in 1994. Generations of gamers had grown up with the Ultima series, and the possibility of creating a literal Avatar (the moniker of the series’ protagonist) in a virtual Britannia was too good to pass up.

Meridian 59’s 3D world was a technical achievement, to be sure, but it was nowhere near as efficient as Ultima Online’s 2D sprite-based world. With a top-down, sprite-based approach, Origin Systems was able to balance latency with an increased world size. One of the main criticisms of Meridian 59 was how crowded it could feel, so the sprawling map of Britannia, with its cities, mountains, forests, caves, oceans, and rivers felt positively colossal by comparison.

It wasn’t merely the size of the world that captured the imagination, but the scale at which players could interact with it. The skill system in Ultima Online reflected the developer’s desire to build not just a game, but a virtual world. Skills that the player can develop include trades like carpentry and blacksmithing, and the skill point limit meant that, if you wanted to reach the highest levels in these skills, you had to dedicate a large part of your character development to non-combat skills. A player, if they wanted to, could pursue an entirely mundane existence, working as a lumberjack in the forest, or maybe a traveling bard, playing music in taverns around Britannia. Not only did the Ultima Online community support roleplaying, but the game provided the tools to make it happen.

Ultima Online’s massive success turned industry heads, and within the space of a few years, everybody was trying their hand at creating MMORPGs. As is so often the case with trends, this flooded the market with new games, and not all of them succeeded. The next two years saw the release of EverQuest (Verant Interactive, 1999) and Asheron’s Call (Turbine Entertainment Software, 1999), completing what many refer to as the “big three” of first-generation MMORPGs. In Asia, a development fork of Nexus: The Kingdom of the Winds resulted in Lineage (NCSoft, 1998), a game whose success in Asia dwarfed anything Western MMOs had achieved in their own market. Lineage would eventually achieve major success in penetrating the Western market too.

By the late 90s, a status quo had been established in the MMORPG market. Players typically devoted dozens of hours per week to playing them, and individual game sessions were significantly longer than sessions for other games. Furthermore, there was abundant evidence that most players were more than happy to spend a regular monthly fee playing these games. The social element of MMORPGs saw tight-knit in-game communities develop. The emotional attachment players developed with one another and the characters they had invested so much time in was a major factor in preventing them from going to another game.

In MMOs, developers could rely on steady cash flow and a captive audience, too absorbed in this game to go and try that competitor’s offering. MMORPGs were seen as a cash cow, and even companies that historically had no fingers in the gaming pie were suddenly establishing “interactive entertainment” divisions to get a slice of the action. One of the first companies to do this was Vircom, a French-Canadian email security company, which established Vircom Interactive. Their big contribution to the genre, The 4th Coming (1998), is one title that I personally sunk many hours into.

The 4th Coming is, in my opinion, a game that deserves far more recognition for what it achieved. Gameplay was heavily influenced by Blizzard’s 1996 action RPG Diablo, making The 4th Coming the first example of a massively multiplayer action RPG, a genre that has been enormously successful in recent years thanks to Path of Exile (Grinding Gear Games, 2013).

Vircom Interactive was also unique in its approach to distributing its game. Most MMO developers kept control of their game servers. All Ultima Online servers were administered by Origin Systems, all EverQuest servers were managed by Verant Interactive, etc. This ensured that the developer could maintain control of the player experience, but more importantly, it meant the developer kept all the income from subscriptions. Vircom Interactive operated its own servers for The 4th Coming, but it also licensed out the hosting software to anyone who could afford to pay the licensing fees. As a result, The 4th Coming servers existed all over the world (with a high concentration in Europe), and each server could be configured for a slightly different experience. Some of the hosting companies (such as ISPs) were able to provide the game for free due to alternate revenue streams (offering the game as part of an internet access package, for example). This ability to play for free, in a genre that typically charged monthly fees, gave thousands the opportunity to experience the magical brand of online community that only an MMO could provide.

The years that followed, into the early 2000s, saw a huge explosion in the MMORPG genre, with several games moving away from the typical fantasy setting. Anarchy Online (Funcom, 2001) took the MMORPG genre to a science fiction setting for the first time, and RuneScape (Jagex, 2001) demonstrated the incredible things that could be achieved in a browser game using the Java programming language.

By 2003, many of the first-generation MMOs were beginning to release sequels, to limited effect. What many studios discovered was that, much like players were unlikely to change to a different game due to their attachment to their existing community, they were similarly apprehensive about changing to a sequel. Many sequels, like EverQuest II and Asheron’s Call II, split the player base, ultimately sabotaging the very communities they had created. And while many MMOs had weathered the dotcom crash relatively well thanks to their stable subscription income, many others collapsed under increased financial pressure. The first generation of MMOs had well and truly ended.

MMO sequels tended to be less innovative in their approach as well, and most simply presented a new world map with better graphics. Meanwhile, new games on the scene were taking risks and carving out their own corners of the market. Star Wars Galaxies (Sony Online Entertainment, 2003) swept up just about every Star Wars gamer that existed at the time with the promise of being able to be the next Han Solo or Boba Fett, while EVE Online completely altered the perception of what an MMORPG could be. The genre was increasingly beginning to detach itself from the “RPG" portion of its acronym, and MMO design began to incorporate other genres, as with the MMOFPS PlanetSide (Sony Online Entertainment, 2003).

In 2004 came the second major event in MMO history, and one that permanently changed the genre, for better or worse. For many years, Blizzard Entertainment had been closely watching the MMO genre, learning from every success and failure, and quietly developing its contribution to the genre. November 2004 saw the release of World of Warcraft, set in the beloved Warcraft franchise. No other game in the genre’s history has had such a monumental impact, and even the modern World of Warcraft game struggles to achieve what it once did.

The success of World of Warcraft came at a time when MMOs in general were beginning to fall out of favour. In a case of “there ain’t enough room in this town for the both of us”, the sweeping success of World of Warcraft crushed everything in its path. Scores of MMOs since have tried to emulate World of Warcraft’s success, and several existing MMOs tried to reinvent themselves in the style of Blizzard’s title, but none succeeded. Depending on who you ask, World of Warcraft is either the pinnacle of the MMO genre, or it is the game that ultimately killed it.

Recent years have seen a noticeable resurgence in the popularity of classic MMOs. 2019 saw the release of World of Warcraft Classic, which replicated the state of the game in its early days. Thanks to the rise of mobile gaming, other MMOs like Runescape have similarly experienced a slight resurgence in popularity. Thanks to unlicensed private servers for games like Star Wars Galaxies and Ultima Online, legacy games continue to survive thanks to enterprising players who, in some cases, are reinvigorating games with entirely new content.

MMOs are, in many ways, the original social network; it is part of what made them so incredibly successful in the days before Facebook. They created the very concept of an online community, and the experiences of MMO players in their respective games are often as important and memorable as events in their personal lives. These communities, like no other game community, are truly enduring. One need only look at the in-game memorials that players create when a fellow player passes away. There is something deeply moving about witnessing the digital avatars of people, who may never have met, genuinely mourning the passing of one of their compatriots.

Over the next few articles, I want to go back and revisit some of these Ancient Worlds. While some still thrive, others hold on by a thread; game worlds that once hosted thousands are home to only a few dozen players. In each part, I will focus on one particular game, and speak to the players that still spend their spare time keeping these communities alive. In doing so, I hope to learn more about what it is that drives the MMO player psyche and community. Perhaps, in doing so, I can do my part in reinvigorating them in some way, and if not, then perhaps the best I can do is just ensure that they are not forgotten.