Ancient Worlds, Part 4: The 4th Coming

What could have been a cynical cash-grab turned into much more with The 4th Coming

Last time on Ancient Worlds, I covered the history of Meridian 59 (Archetype Interactive, 1996), one of the most important MMOs ever released. It was the product of two inspired and passionate game developers who sought to innovate and bring joy to their players. Money was a concern, but never the goal.

The 4th Coming, released in 1999 by Canadian company Vircom Interactive was, in every sense, the polar opposite of Meridian 59. This wasn’t a passion project cobbled together in the parents' basement — it was produced by an interactive entertainment subdivision of a "Dotcom Boom" IT company. It didn’t innovate or leave a lasting legacy for the genre. It was released in 1999, just in time to capitalise on the booming MMORPG trend of the late 90s. Marketing didn’t promise an innovative experience — they promised a game that was “just like" other well-known games. In hindsight, The 4th Coming must have seemed destined for failure. It should have failed, in the face of so much competition. But it didn’t. The 4th Coming survives today, against all odds.

How did this happen? I’m not sure, but I have my theories. The 4th Coming was one of my first MMOs, and I recall my days in its utterly derivative fantasy world fondly, as do many others. Hopefully, by looking back at the history of the game and speaking to some of its remaining players, we can answer what made this seemingly forgettable game so unforgettable.

There was a time long ago…

So begins the outline of the game’s story, detailed briefly in the in-game introduction and on the website the4thcoming.com (archived from 2003). The 4th Coming was the very definition of derivative - a generic fantasy fiction game designed to capitalise on the MMO trend that had been spearheaded by the likes of Ultima Online and Meridan 59. The 4th Coming was an uninspired release in 1999, a year that some consider to be the very height of the PC Gaming Golden Age.

It might seem unfair to simply dismiss The 4th Coming as little more than a cash grab, but the evidence speaks for itself:

"Vircom Inc. devoted more than two years to develop The 4th Coming (T4C), a graphical multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game Server as an answer to the exploding online gaming market. T4C was designed with a unique clientele in mind: that of telephone companies, leading Internet Service Providers (ISPs) and Online Gaming Networks (OGN) around the world."

- Vircom Inc.'s product summary for The 4th Coming

Vircom is a Canadian IT company from Quebec that is still in operation today (Vircom.com). According to their website in October 1997 (courtesy of The Internet Archive), Vircom specialised in "high quality and leading edge software for the online industry". Their products included the MajorTCP/IP product suite, an ActiveX Telnet Client, a proprietary RADIUS server, and other online authentication and security products geared towards ISPs and other Dotcom Boom clients.

The earliest reference I could find to The 4th Coming was from The Gamemaster, a site that originated in 1989 as a dial-up Bulletin Board System. Though details are scarce, it appears that by 1997 The Gamemaster was owned and operated by Vircom Inc. In December 1998, The Gamemaster announced Vircom's development of The 4th Coming:

The 4th Coming was released on 14 May 1999 after several months of beta testing, and as I've already hinted, it would be easy to dismiss the game as a forgettable cash grab. But, surprisingly, The 4th Coming was a pretty unique game for the MMO genre, both from a design perspective and from an administrative perspective. In fact, one might argue that The 4th Coming was the first Diablo-style Action RPG MMO - released almost 15 years before games like Path of Exile truly lifted that specific genre to prominence.

The first online Action RPG

The idea of defining a "first" in game design is somewhat of a futile endeavour, but there is some value here. Most first-generation MMORPGs tended towards more complex systems and mechanics, with deep character customisation and a broad set of skills to work on, many of them non-combat skills (like Ultima Online's crafting systems). The 4th Coming went against this trend, for the most part. The game's RPG mechanics were entirely focused on combat and magic skills, with attribute development focused on acquiring specific gear.

Strength, Endurance, Agility, Intelligence, and Wisdom form the core stats, in classic RPG style. These influence secondary stats like hit points, mana, armour class, and attack rating, as well as determining what sort of gear the player can wear. The 4th Coming is a classless game - you can build your character any way you like - but a few builds emerged, each focused around martial combat, healing and buffs, damage dealing magic, or some mix of the above. My personal favourite build was the Battle Mage - mixing the armour and martial ability of a warrior with the damage-dealing spells of a pure Mage.

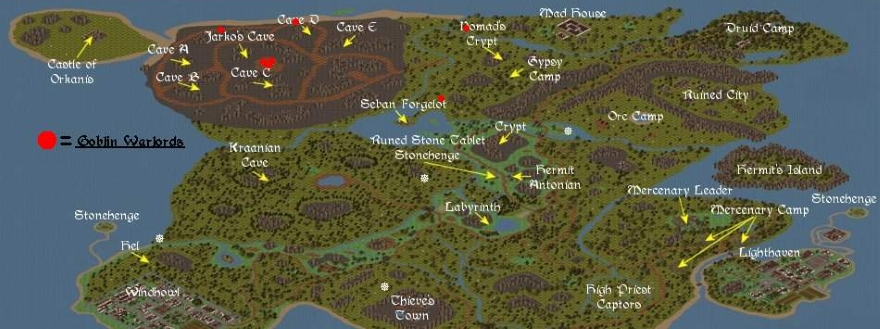

Like most MMOs of its day, The 4th Coming combat featured auto-attack - somewhat offsetting any latency issues that might have arisen in the days of dial-up internet. Beyond that though, T4C more closely resembled a very rudimentary version of Diablo. The world was made up of several discrete zones filled with hordes of monsters, and progression through the world was limited to what your character's level could feasibly face.

That's not to say T4C was anything close to a Diablo competitor - gameplay was somewhat clunky, graphics were poor even by 1999 standards, and the quests were pretty monotonous overall; the very first quest in the game, known as the Errand quest (due to the keyword you use to start it) asks you to slay 15 rats in the temple dungeons - and yes, the rats carry gold. But, as far as MMORPGs went, The 4th Coming was offering something slightly more reminiscent of an Action RPG, and that was different.

Unique licensing

Despite a somewhat different twist on MMO mechanics, The 4th Coming didn't really offer anything particularly unique, and were it not for a clever business decision on the part of Vircom, it's highly likely that T4C would have vanished into the crowded late 90s MMORPG market.

Other MMORPGs at the time, and many in operation today, operated on a server-client model - the player (client) would have all the local assets required to run the game installed to their computer, and would connect to a server to play with other clients. MMO servers were usually managed by the studio behind the game, and hosted at sites globally in order to minimise latency by virtue of geographic proximity. High-speed internet connections, distributed content delivery networks, and vastly improved networking protocols and code have somewhat minimised the importance of this geographic proximity today, but in the days of dial-up internet, every millisecond counted.

Having a server managed by the developer and/or publisher had multiple benefits - they could manage the experience to ensure it met their creative vision and maintained a certain standard of behaviour, and it also protected the trade secrets of how their game was specifically constructed. The downside was that, especially in these early days, running a network of globally distributed servers capable of hosting large numbers of players was extremely expensive in money and resources. While gamers were no longer paying $6 per hour to play MUDs like Neverwinter Nights, monthly subscription fees for Ultima Online, EverQuest, or Meridian 59 were still a barrier to uptake.

Vircom took a different approach - outsourcing the hosting. As explained above, T4C was an MMO marketed specifically to ISPs as something they could bundle with their subscriptions for added value. For a licensing fee (the amount of which I have been unable to determine in my research), an ISP would be provided with all the tools required to host their own MMORPG server, and ISPs were likely to already have some of the infrastructure to make that happen.

It wasn't only ISPs that hosted T4C servers - there were "official" Vircom servers, and many Dotcom Boom IT startups too. The benefit was that many server operators could rely on alternate sources of income to offset the cost of running an MMO, and there were a number of free servers. In the crowded late '90s MMO market, this was unheard of and was a major reason why T4C was the first MMO experience for many gamers. I discovered T4C on one of the CDs that accompanied an issue of PC PowerPlay magazine, and before long I had joined a free server hosted by eAcceleration, an IT security company.

It is because of the server licensing model that I believe T4C survived as long as it did, and why it still survives today. However, that perspective carries the benefit of hindsight. At the time, there was a concern that the model had undermined T4C's chances of competing with the MMORPG genre's big-hitters. Here's T4C lead designer Jean Carrieres talking to Shane Benson from T4CPortal.com in March, 2000:

"Another disappointment (even if you only asked for one) is the general structure of our marketing approach. We still stand behind the concept of creating a game that the "small guys" could buy and provide to their user base, but in retrospect, we wish we had created a better structure behind the business model, perhaps something more franchise-like, centralizing the marketing and ensuring a consistent quality feel across all servers. It's something we'll definitely keep in mind for our future projects."

It's true that T4C's server licensing model did lead to a distributed community, and perhaps that in some ways undermined the Network Effect that MMOs rely on. But the model also created resilience. As we've seen numerous times over the past couple of decades, unsustainable MMOs are usually shut down, and if the studio that created that MMO is managing all of the servers, then the game shuts down entirely, much like Asheron's Call (Turbine Entertainment Software, 1999) or WildStar (Carbine Studios, 2014).

T4C's distributed servers have provided some degree of protection from this. As the popularity of T4C waned due to the emergence of second-generation MMOs and eventually the World of Warcraft era, servers began to close down. But, as one T4C server would shut down, some portion of the community would inevitably move to a surviving server, giving the population there a boost.

Acquisition by Dialsoft

Despite the inherent resilience to network collapse through free servers and distributed licensing, the emergence of World of Warcraft in 2004 was like a tidal wave hitting the genre, particularly for Western MMORPGs. By 2006, Vircom was seeking to unburden themselves of The 4th Coming, and a shutdown seemed imminent - but salvation came in the form of a long-time T4C server operator, Dialsoft.

Dialsoft was the owner of Realmud, one of the oldest and most well-known T4C servers. Once Dialsoft president Marc Frega acquired the T4C source code and licence from Vircom, the game was handed over to a team of Realmud staff and players who would take the lead on the next chapter of The 4th Coming's life, closing the book on the Vircom era. Since then, Dialsoft and the T4CDEV team have greatly enhanced the original game and expanded the game world.

A Virtual Village

I played T4C religiously on eAcceleration between about 2001 and 2002, but like many other players, I eventually moved on to other games (including World of Warcraft in 2004). Though player counts have dwindled over the two decades since T4C's release, there is still an active community supporting the game across multiple servers.

The majority of players today are active on the "official" Realmud servers during US and European times, so if you're tucked away in my part of the globe (Australia), you're not likely to run into many other players. Even during peak population times, the player base is small, but it endures. I spoke to a few T4C players to try and understand what keeps them going. After all, MMOs most often thrive with a large and active community, and those years are mostly in the past for T4C.

I spoke to three players from Dialsoft's T4C community Discord channel - "Tonka7", "Epsilon" and the current Director of Operations for T4C, "Mouse". Unsurprisingly for a community behind a nearly 25-year-old game, all three have long been dedicated fans of The 4th Coming. Tonka7, Epsilon, and Mouse first started playing in 1999 on the AR Internet, GOA, and ACS Plus servers respectively. Between them, they had also delved into other MMOs over the years (such as Asheron's Call, Dark Age of Camelot, Guild Wars and World of Warcraft), but there was something special about The 4th Coming that kept them coming back.

All three highlighted the community as a critical component of what keeps them engaged. In the words of Epsilon:

"The social aspect [keeps me coming back]. The tight-knit community. Nothing quite like it. The accessibility of the chat features, and the small server population meant that the more you played on a server, the more you knew every player's name and actions, and could act accordingly. It was very unique in that regards. To my knowledge, no game ever reproduced that unique sense of belonging."

Even Mouse, who took a three-year break from the game, highlighted how the community had a role in drawing him back in:

"...other then the 3 year break, I have been around T4C in some [way] since 1999. As I have told my wife more then once, I am not sure if it's dedication or stupidity that has kept me around. And then, at other times, I know it’s a little bit of both LOL. In reality, it’s the love for the game and the community..."

The importance of "community" in MMOs is what I think defines the genre more than anything else, and what makes MMOs a truly unique sort of game. Anyone who has spent a decent amount of time playing games of the genre understands the incredible allure that the sense of community can provide. I've personally found myself sucked back into games like The 4th Coming, World of Warcraft and Ultima Online numerous times over the years, trying to recapture the unique feeling of belonging that only an MMO offers.

What makes an MMO community unique compared with other social networks possibly has something to do with their low-stakes nature; unlike typical day-to-day interactions, an MMO community will often have a low barrier for entry. Often all you need to do to join one is to respond to a guild recruitment message posted in a chat channel. The nature of online games also provides a degree of anonymity, and thereby security, in that you only need to share with others what you want them to know. Lastly, the nature of social engagement is centred around a hobby - gaming. MMO players are taking part in a shared interest, and this lends an air of positivity to the relationship that one might not necessarily attain from a social network in an environment like the workplace.

Often, the shared experiences of an MMO like T4C can lead to genuine friendships developing outside the confines of the game. As Tonka7 recalls:

"...when I first started, my brother and I went to a couple of BBQs with others from the server, went to someone's wedding from the game. I have heard of people meeting up a lot in America, and I know a few people that have travelled to meet others which is cool. I'd like to meet a few more people one day that I've played with."

The experiences of Epsilon and Mouse echoed Tonka7's. Epsilon's first face to face meeting with other players had been organised through the game's community forums when he was only 15 or 16, and many of the friends he made during these years are friends he still talks to 25 years later. Mouse similarly made several friends through T4C, and though many of them no longer play, they still remain friends.

Outside of the shared sentiments on the importance of the community, current motivations to keep playing T4C are less consistent. I asked whether they felt as if they had experienced all the game had to offer, and responses were mixed. Tonka7 highlighted the somewhat repetitive grind, as did Epsilon. However, Epsilon highlighted that there are many ways to experience content that can make the experience refreshing, and Mouse also stressed the importance of mindset:

"I have done a little bit of everything with T4C and keep learning new things even after 20+ years of being around. It's all about how you look at things and what you can put your mind to doing."

The 4th Coming today

As part of this series, I seek not only to dig into the history of the first generation of MMORPGs but also to assess whether they are worth diving into for a modern gamer today. So far, The 4th Coming is possibly the most difficult game for me to objectively assess. It was a huge part of my gaming life for a number of years, and I look back on it with undoubtedly rose-tinted glasses. Dialsoft and T4CDEV have done a great job refreshing the game aesthetically, but the dated mechanics remain.

Ultimately, there's no harm in trying it - The 4th Coming is free and is available on Steam. I'd recommend getting a couple of friends together, reading up on the gameplay a bit, and diving in. The community is generally quite welcoming, and will no doubt see an influx of new players as a curiosity worth chatting to. In researching this article, I took a romp through the Lighthaven Temple dungeons for the first time in almost 20 years, and I soon found myself talking to another player who kindly buffed me with his magic spells and gave me some friendly advice.

Every MMO has its own unique parlance, whether it is the "salute" emoji in EVE Online ("o7"), or the usage of "ding" to represent a level-up in World of Warcraft. The 4th Coming has its own social tradition - when a player announces that they have leveled up, the general response is "WTG!" - Way To Go! It's a bit daggy, but I think it is a tradition that ultimately represents a positive community, one where others celebrate your gaming achievements.

Tonka7, Epsilon, and Mouse all conceded that there are toxic elements in the community, but toxicity in the world of modern multiplayer gaming is hardly something new. In fact, from my own personal experiences, I would argue that players of some modern multiplayer games might actually be taken aback by the overwhelmingly welcoming nature of the T4C community - even if a few of them take a "sink or swim" approach to new players. In the words of Epsilon:

"New players can bring new friendships, and a revitalization of the game. They can contribute to the overall health of the community, increase social interactions, and potentially lead to new content or updates from developers.

However, it's important to note that each player within the T4C community may have their own unique perspective on this matter. Some players may be open and welcoming to new players, recognizing the benefits they bring, while others may be more cautious or hesitant. Ultimately, the reception of new players will depend on the individual attitudes and reactions of the existing community members."

The Future of T4C

Where does Dialsoft and T4CDEV intend to take The 4th Coming in the future? According to Mouse, T4C's Director of Operations, there are no plans to open-source The 4th Coming as has been done with Meridian 59, but there is still an active development team keeping the game up to date. But keeping an old game like this running comes with some challenges. "Working with a 20+ year old code base takes time to update and maintain without breaking the game," said Mouse.

The great advantage that old MMOs have when it comes to survivability is that they only get easier to host as the years pass. T4C has never been a particularly taxing game to host, owing to the fact that it was originally developed as an approachable method for private companies to establish themselves in the MMORPG market. The minimal resources required to host it, combined with an enduring player base, indicates that we are likely to see T4C continue to endure well into the future. Epsilon offered his own thoughts on the enduring nature of T4C:

"T4C has already demonstrated a remarkable longevity since its release in 1999, and its dedicated community has played a significant role in sustaining the game over the years. However, it's important to recognize that the future of T4C will likely depend on the continued support and commitment of its developers, as well as the ongoing engagement and passion of its player community.

T4C has the potential to endure and provide enjoyment for its players for years to come. However, the ultimate trajectory of the game can only be determined by the collective actions and decisions of the developers and players."

In the cavalcade of first-generation MMORPGs, it would have been easy to discard The 4th Coming as little more than a cash grab by Vircom. The game was comparatively late to the scene, with dated graphics and a gameplay loop that one might argue is overly simplistic. But The 4th Coming thrived and endured far beyond anyone's wildest expectations, thanks to an unexpected uniqueness and strong community spirit.

In the next edition of Ancient Worlds, we'll take a look at another 1999 MMORPG, one that would come to have an enormous influence on the future of the genre, and herald a new age of 3D MMOs - EverQuest.