Ancient Worlds, Part 3: Meridian 59

Meridian 59 helped give birth to the MMORPG genre and lives on today

1996 was a watershed year for MMOs. Though Origin System’s Ultima Online was still many months away, the concept of huge online worlds with hundreds of players was already on everyone’s mind. This was the dawn of the “Dotcom Bubble”, and access to the Internet was becoming increasingly approachable and affordable for the average household.

1991’s Neverwinter Nights (Beyond Software) had already hinted at what might be possible for the future of online gaming, and several studios were making significant investments in the newly emerging “massively multiplayer” genre. Yet, despite significant interest from large studios like Electronic Arts and Sierra On-Line, it was an unlikely pair of brothers working in their parents' basement who would truly innovate MMOs, setting the stage for the future of the genre.

Meridian 59, by developer Archetype Interactive, released in 1996, at the dawn of the MMORPG golden era. It preceded Origin’s behemoth Ultima Online by several months, and while it wasn’t the “first" in the genre (if that term even means anything in an iterative field like game development), Meridian 59 stood out from the pack thanks to its immersive, fully-3D world — the first of its kind in the genre.

Conception & Development

Meridian 59 was the brainchild of brothers Chris and Andrew Kirmse, whom I had the pleasure of interviewing in late 2021 (see above). The trajectory of the Kirmse brothers to MMO royalty began with an RPG known as Scepter of Goth (1983). Alan E. Kleitz’s Scepter of Goth was one of the first commercial examples of the “Multi-User Dungeon” or MUD. Like the genre-defining MUD1 by Trubshaw and Bartle, Scepter of Goth was a multiplayer, text-based, role-playing game, and is considered foundational to the eventual formation of MMOs. It was also foundational to the Kirmse brothers’ aspirations to get into MMO game development.

Scepter of Goth ran on a single IBM PC XT, with hardware to allow up to 16 modems connected to it at once. Once connected, players could explore the city of Boldhome, for a cost of around USD $3 per hour. Given that the hourly minimum wage when Scepter of Goth launched was USD $3.35, this wasn’t exactly a cheap hobby to pursue.

By the time they were at college, the Kirmse brothers had been exposed to LAN multiplayer games like XTank (X Window System, 1988), and the idea of pursuing game development began to solidify. As Andrew Kirmse states, “we kind of had this idea that it would be cool to write a game like Scepter — but there’s this internet thing”. The early 1990s saw the internet open up to commercial ventures, and the possibility of a game like Scepter of Goth running over the internet (rather than a closed dial-up network) became a reality.

There’s a heavy dose of serendipity in the creation of Meridian 59. Andrew Kirmse notes:

“There were kind of a few things that came together at the right time — we’re really interested in games, we’re at colleges where there was the internet (because a lot of colleges didn’t have internet) and… we knew enough. We didn’t know too much, but we knew enough. I think if we knew too much…we would have known how hard it was, and we wouldn’t have bothered; so, we’re kind of right in that sweet spot…”

It was a common tale in the 80s and 90s game development scene before the industry had solidified itself as the well-oiled commercial machine it is today. The right people in the right set of circumstances, with a little bit of luck, can make history — and that’s exactly what happened with Meridian 59.

By 1993 (leading into Chris’ sophomore year at college), the Kirmse brothers had already written some games and software. Thanks to his work to that point, Chris landed a summer internship at Microsoft. By sheer coincidence, Andrew secured a summer job with Microsoft at the same time in a different division.

As Microsoft interns, finances were limited, but the Kirmse brothers knew that they wanted to make a game — they just needed the right development environment. Windows 3.1, the prevailing Microsoft OS at the time, was by all accounts a “nightmare” to develop for, but Windows NT 3.1 was just coming out of beta. Compared to Windows 3.1 development, NT was significantly better and more reminiscent of Unix for software development, which is what the Kirmses had learned at school. The cost of a couple of Windows NT copies and the compiler was thousands of dollars alone, but their positions as Microsoft interns gave them a significant discount and made it affordable. So it was serendipity once again that extended her graceful hand and granted Chris and Andrew the perfect opportunity to kickstart their dream.

Of course, there were plenty of games around at the time, but most ran under DOS rather than in Windows. The Kirmse brothers already knew that they wanted to write a “client-server” game using TCP/IP, and this precluded DOS, which at the time did not support it. Linux, though technically an option, had very limited support for games (certainly no commercial ones), so that left Windows NT. Though Windows 95 was not yet officially announced (it was known only under the code name “Chicago”), Microsoft had already committed to ensuring Windows 95 backward compatibility with Windows NT applications. Now, Chris and Andrew not only had a more permissive development platform with support for the networking protocols they needed, but they had the confidence that anything they developed was somewhat future-proofed as well. And so, with the stars aligned and all the pieces on the board, the story of Meridian 59 began in earnest.

Just down the street from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where Andrew was then studying, was Looking Glass Studios. Looking Glass was fast approaching its zenith — Warren Spector’s transformative immersive simulation Ultima Underworld was in the rear-view mirror and would shortly be followed by a beloved sequel, Ultima Underworld II: Labyrinth of Worlds, and another critically acclaimed game, System Shock. It was there that Andrew, freshly graduated, decided to try his hand at entering the games industry.

“I didn’t want to [work at Microsoft] for 30 years… So, we both kind of said… we have this game thing that we maybe want to do — let’s try that. If it doesn’t work, we can, I guess, go work for Microsoft for 30 years.”

Andrew and Chris were both admittedly very naive when it came to the games industry. They knew about it, of course, and they played a lot of games. Yet it was their naivete that made Meridian 59 possible. Insulated by that innocence from the fact that games often required dozens of developers with enormous budgets, they told themselves that sure, they could do that.

The initial prospect of joining Looking Glass Studios (or Papyrus, another studio that they had considered), eventually gave way to Andrew’s decision to stay at MIT and complete his master’s degree in computer science. In the summer of 1994, neither of the brothers had landed internships, which would prove pivotal in realising the dream of Meridian 59. That summer, the two brothers committed to three full months of development. Work continued over the following college year, if a little more sporadically. Though they were both still studying, the game consumed much of their spare time. As Andrew recalls, “we would get up at noon and we would work 16 hours, and we would go to bed at 4 AM, and then repeat it seven days a week…I’ve never worked so hard”. And for precisely zero income, no less.

By the summer of 1995, the 3D engine was quite mature, and was integrated with client-server networking. As Chris describes, “nothing else out there like it existed”. This game had initially begun as a desire to recapture the magic of Sceptre of Goth but with graphics — 16 players connected to a server, over a dial-up connection. But, by the summer of 1995, it was eminently clear their game was about to become so much more than that.

Meridian 59 was released in alpha in 1995, and it was during this initial test that Andrew recalls one of his fondest memories. Around December 15, 1995, after launching the alpha test, the Kirmse brothers endured a sleepless night of anticipation and excitement. The next morning, Andrew asked his brother, “I wonder if anyone has seen the game yet?” So, of course, they logged on to discover that, yes, there were indeed still a few players on even at this hour.

Andrew recalls chatting to one of the players who had successfully completed the game’s early quests and figured out all the mechanics. Shocked, Andrew asked if they played a lot of games, to which the player responded, yes — and that he had written Legends of Kesmai, a MUD that could trace its lineage all the way back to 1985. Here they were, a couple of young college graduates, who against the odds had thrown together one of the most anticipated games of the decade, and they were generating interest from developers of the games that had inspired them.

The development team behind Meridian 59 had also expanded over this period. Among them was Damion Schubert (the first to join the project), eventually followed by Rich Vogel, Damion’s brother Tim Schubert, brothers Mike and Steve Sellers (who took on the essential role of securing investment), and Keith Randall, Andrew’s college roommate. By the time 1996 rolled around, Meridian 59 was no longer a passion project cobbled together in the Kirmse brothers’ parents’ basement — this was the hotly anticipated inaugural game from Archetype Interactive. The anticipation was so great that 17,000 players had already joined the game’s public beta by April of that year.

By the late 1990s, the games industry seems to have recognised the inherent potential of online “massively multiplayer” games, and there seemed to be a sprint from all corners of the industry to get a slice of the next big thing. But the Kirmse brothers, naive and somewhat isolated from the rest of the industry, they didn’t seem to notice. With every waking hour committed to either college study or game development, there wasn’t any time to look around at what everyone else was doing. And, when you look at Meridian 59 compared to its contemporaries, it shows.

In March 1996, as Meridian 59 was heading into beta, the team started to generate a bit of press. Origin Systems, who were then working on their own MMO, Ultima Online, saw the hype around this new game from an upstart east coast developer and immediately scrambled to take back the initiative. With the resources of mega-studio Electronic Arts behind them, they announced their own beta period shortly after Archetype Interactive, and consumed all the press coverage (the Ultima series was one of the longest-running and most highly regarded RPGs, after all).

Though the immense corporate might of Electronic Arts somewhat let the wind out of Meridian 59’s sails, this must have been a vindicating moment. Here they were, an “indie dev” long before the term had even been coined, putting a major studio on the defensive. Speaking to an Origin Systems employee some years later, Andrew Kirmse recalls that, upon hearing about the hype for Meridian 59, Origin immediately pulled several staff off the upcoming Ultima IX: Ascension to work on Ultima Online. Chris recalls that, after the release of the Meridian 59 beta, he did a reverse DNS lookup of connected users — and a sizeable portion of those players were connected from Origin Systems and Verant Interactive (developer of 1999’s EverQuest). As vindicating as this may have felt, though, it was also a big reality check for the tiny team behind Meridian 59 — how the hell were they going to maintain this momentum when it seemed that the industry’s biggest players were poised to crush them into the dust?

With a successful alpha and beta test behind them and an unquenchable thirst for more from gamers, it is perhaps unsurprising that major studios started to take an interest in acquiring the lucrative rights to what would be the first 3D MMO game. Kevin Hester, a programmer for California-based developer 3DO, brought the game to the attention of 3DO CEO Trip Hawkins. Trip Hawkins was a household (and some might say infamous) name in the games industry — he had founded Electronic Arts back in 1982 and then The 3DO Company in 1991. Before long, Mike and Steve Sellers met with Hawkins, followed soon after by a meeting in California with Andrew and Chris.

Only a few short years after its inception, Meridian 59 was drawing the eyes of one of the biggest names in the industry. Archetype Interactive’s maiden title was on the lips of every gamer, and things were looking up. It couldn’t get any better, could it?

As it turns out — yes, it could get a whole lot better. In a combination of what was possibly some convenient omissions on the behalf of 3DO and a good dose of naivete on the behalf of Archetype Interactive, the acquisition was indeed too good to be true. The Kirmse brothers had settled for USD $5 million in 3DO stock, but little did they realise that 3DO was already in dire straits. 3DO’s venture into console hardware with the Panasonic 3DO was an abject failure, and while the company acquired Might & Magic developer New World Computing in 1996, Meridian 59 would be their first PC game. Soon after the acquisition, the Kirmse’s stock lost 75% of its value, and it became immediately clear that 3DO sought to recoup their investment as soon as possible by pushing Meridian 59 out the door in time for third quarter financial reports. Not only that, it seemed that 3DO intended to use Meridian 59 merely to build experience for their own MMO, Project Wintergreen.

Meridian 59 was pushed to release on 27 September 1996. Sales did not meet expectations — 3DO had gutted the development team in the final months, and marketing was lacklustre to say the least. In the face of stiff competition from Origin’s upcoming juggernaut Ultima Online, things looked grim. Chris and Andrew had argued that Meridian 59 should given away for free to as many people as possible, with costs to be recovered with subscription fees; it was an idea decades ahead of its time, and today subscription-based free games are commonplace. But 3DO insisted on making their money upfront, and slapped the standard retail pricing on the game.

As I’ve previously discussed, an MMO is not something entered into lightly. They are time-consuming and expensive, so the opportunity-cost equation has significantly higher stakes for MMO gamers. Meridian 59 was an unknown franchise coming from a studio with well-documented troubles, and a troubled late development cycle. On the other hand, the genre was blossoming like never before, and there were a whole lot of increasingly attractive alternatives.

Despite these troubles, Meridian 59 attracted a core base of dedicated players who completely immersed themselves in a fully-realised online world unlike any other. Sales figures were poor, but critical reception was solid, and the game won several awards and accolades from prominent press outlets like Computer Gaming World, CNET, and The Adrenaline Vault.

Unfortunately, things didn’t improve greatly over the following year, and 3DO seemed unwilling to do anything more than cut their losses. After three years and a whole lot of emotional and physical investment, the Kirmse brothers were exhausted and disheartened with the ugly corporate side of the games industry. 3DO cancelled their “Wintergreen” MMO project, and future prospects at 3DO looked grim indeed for the Kirmse brothers, who sadly walked away from their then-crowning achievement in 1997.

Meridian 59 chugged away for three more years, in the shadow of the true giants of the first generation of MMOs. One has to wonder how those developers at Origin and Verant, now riding high on the rampant success of Ultima Online and EverQuest, felt when they looked at the struggling Meridian 59, the game that they had been so amazed and intimidated by only a few years earlier when logging in for a bit of “corporate research”. Some of Archetype’s original crew stayed on at 3DO to see Meridian 59 through these years, but most eventually moved on to other projects. Finally, in August 2000, 3DO shut the game down, before closing their own doors only three years later in the face of mounting money problems.

It was far from the end for Meridian 59, however. With the investment a typical MMO player makes in their game of choice, they can be relentless in keeping them alive. Enter two Meridian 59 developers, Rob “Q” Ellis II and Brian “Psychochild” Green. Both had worked on the game since the early days, and it meant a lot to them. Together, they formed Near Death Studios in the early 2000s, initially seeking to make their own MMO. But after some discussions with 3DO, they purchased the rights to the recently defunct Meridian 59 and in 2002, relaunched the game, with a new rendering engine and quality-of-life improvements.

Ellis and Green, the adoptive parents of the Kirmse brothers’ beloved game, did their very best to revive Meridian 59 in those years, improving the game in almost every aspect. They continued to be the underdog, however, as a new generation of MMOs was blazing its own trail — Asheron’s Call, Anarchy Online, EVE Online, Lineage, and RuneScape topped the massive list.

Then, in 2004, Blizzard Entertainment entered the arena with its own unstoppable juggernaut that not even the genre’s best performers could compete with. The release of World of Warcraft spelled the end of more than a few MMOs, and the industry still hasn’t fully recovered from the impact crater left by Blizzard’s MMORPG asteroid. Meridian 59, with its small but dedicated community, weathered the reign of World of Warcraft better than many, but dwindling subscribers and increasing costs eventually forced Near Death Studios to shut the game down in January 2010.

Fortunately, it was soon apparent that Meridian 59 was a game that could not be killed. Green and Ellis, announced that they would be handing the game back to Chris and Andrew Kirmse, 13 years after the pair had left 3DO. In that time, they had individually left their own impact on the wider tech industry — Andrew’s influential work at Google can still be felt today, while Chris laid the foundations for the future success of Twitch and Discord with the visionary platform Xfire. These achievements, to name only a couple, are undoubtedly noteworthy. Yet there is something incredibly poetic in the fact that their first truly immense achievement finally found its way back into their hands. Meridian 59, for all its problems and perpetual underdog status, had left the industry with a monumental legacy.

In 2012, the Kirmse brothers open-sourced Meridian 59, ensuring the legacy of the game would not be forgotten. Today, it lives on in the hands of its fans, and as the MMO genre lurches on in its post-golden age, Meridian 59 still occasionally makes the pages of the gaming press, who increasingly look backward to understand how we got to where we are today.

Meridan 59 Today

Meridian 59 is a long way off the peak number of players it hosted in the late 1990s, but thanks to their commitment to open-sourcing the game, Chris and Andrew have ensured it remains resilient to the passage of time. There are several servers to play on, and with modern broadband internet, latency based on geographic location is far less of a concern than it was on dial-up connections in the late 90s. August 2018 finally saw a Steam release for Meridian 59, so the threshold for entry is lower than ever before.

For students of gaming history, there is no reason to not try Meridian 59. It’s free, and as with many ancient communities such as this, there are plenty of friendly players who are keen to welcome new players into the fold. There is, of course, a fair share of grumpy old grognards who will put newbies through their paces as well, but I’m sure it comes from a place of love. It is important to remember, however, that Meridian 59 was particularly notable in its time for its ruthless player-versus-player scene. Don’t let that scare you off, however. That’s all part of the experience.

Joining the “classic” game simply requires a free account at Meridian59.com, after which you can download the client and connect directly, or install via Steam and play through there. There are two official servers, 101 and 102 (with 101 being the more populated of the two). Alternatively, several enthusiasts have launched their own servers. One of the most active is Meridian 420, which continues to modify the game in its own direction, while also maintaining a list of other servers you can play on if 420 doesn’t fit your taste (such as 103, 105, and 112). Several have active Discord servers, and there’s a Meridian 59 subreddit if you want to interact across communities.

The game is certainly not just in “maintenance mode” either, like many other legacy MMOs. It is being actively developed to make it easier than ever for modern players to embrace, without undermining the essence of what makes the game unique. On 14 December 2022, Meridian 59 received yet another update implementing some significant improvements, window resizing among them. Experiencing the world of Meridian 59 using the entirety of your screen real estate can greatly enhance the immersion, and allows you to more closely appreciate what a marvel this game was and continues to be.

The interesting thing about ancient MMOs is that the existing players seem to treat new players as a bit of a curiosity, like a city-slicker wandering into a saloon in the Old West. They will stop and say hello and have a chat (my first experience with "Braz"), or they might offer to take you through some quests or give you a quick tutorial. Or they might just stomp you into dust and move on. Such is MMO life.

There is no question that Meridian 59 is its community. I also had the opportunity to correspond with Josh, who fills a key role as a kind of community manager and administrator for Meridian 59 in its current state. Josh first started playing Meridian 59 during its initial run in his teenage years, then continued playing when the game fell into the hands of Near Death Studios. When the game returned to Chris and Andrew and was open-sourced, Josh came on as part of the Meridian 59 team and has been in that role since.

Sadly, in 2020, Brian “Psychochild” Green passed away unexpectedly at the age of 44. A figure who had loomed large in the history of Meridian 59, his passing shook the MMO community. In short order, Josh and several other players and past developers organised an in-game memorial for Brian, paying their final respects to him in a game that had held such an important place in his heart. Sadly, one of the players who had helped organise the in-game funeral for Brian himself passed away from stroke shortly afterward. Ben, known as “Tiki”, was a huge part of the community’s heart, and the Meridian 59 community gathered once again to farewell another of their number.

The loss of any life in a tight-knit community is tragic — my own communities in other games have endured the same. Yet, in such a small community like Meridian 59, the impact seems amplified. Every loss is felt deeply, and it can feel like a part of the game itself is lost along with the player or developer who had been so instrumental in making it what it was. However, this also serves to demonstrate the strength of the community — not all gamer communities rally around the fallen like the players of Meridian 59.

My interactions with other players in Meridian 59 were limited, perhaps as a consequence of geography. It’s a challenge Oceanic players have dealt with since the dawn of multiplayer gaming. The centre of gravity for many Western player bases is in the US and Europe, and the Oceanic region rarely reaches enough of a critical mass to sustain its own community. Still, MMOs being what they are, you can usually guarantee at least a handful of players online, and there’s no harm in saying hello.

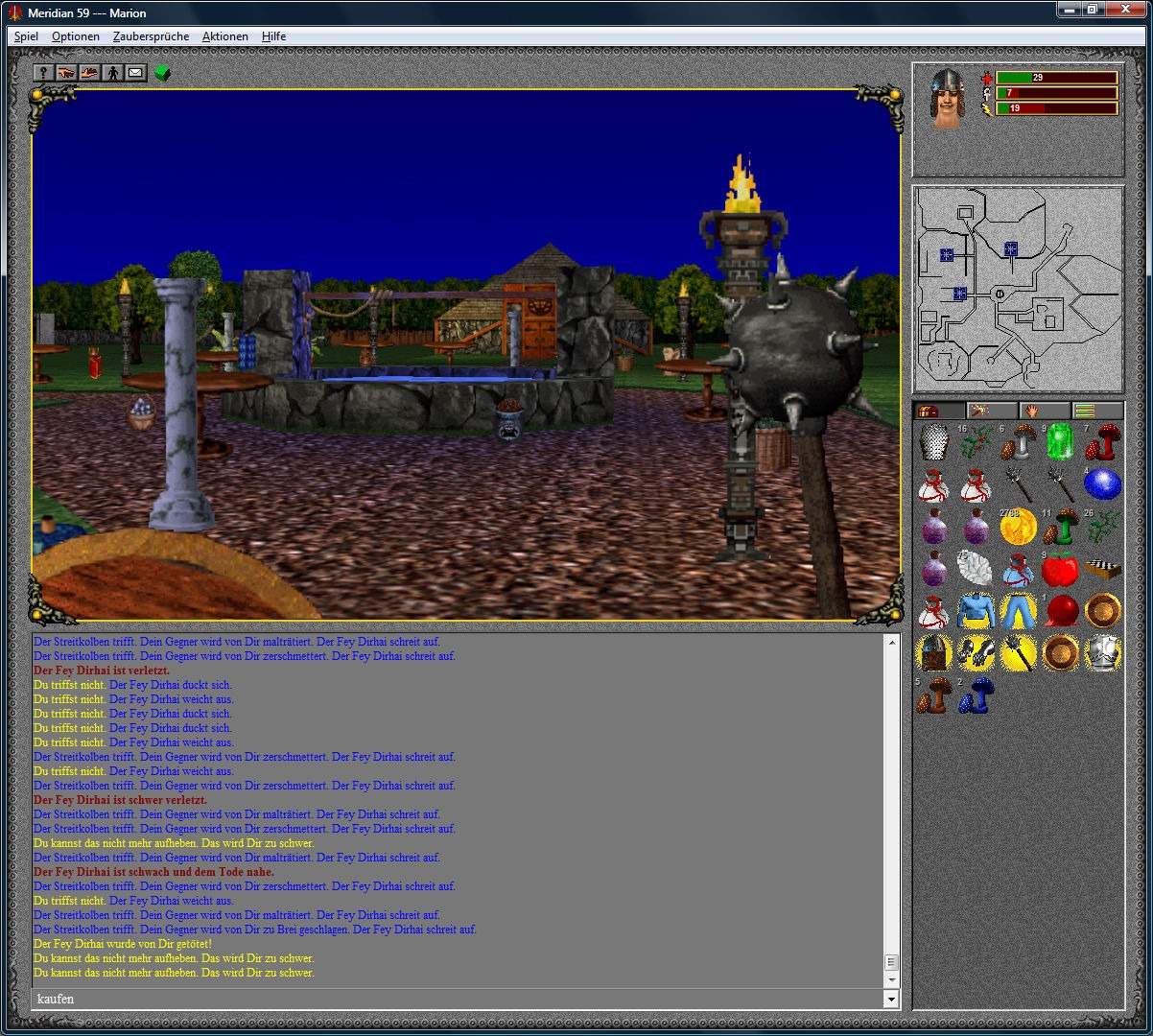

Gameplay-wise, Meridian 59 falls into that strange little period of game development that was post-DOS, but still at a point where not all developers had fully embraced Windows. Games from that era are often a pain to get running (especially 16-bit programs), but Meridian 59’s active development over the past 25 years has avoided those problems. The GUI (at least in the classic client) is aesthetically a product of its time, however, and would look entirely at home on a Windows 95 box.

The Future of Meridian 59

So, what next for Meridian 59? The game’s legacy is unquestionable, its impact is widely appreciated and well-documented, and it is safely preserved thanks to the foresight of making it open-source (a practice far too few studios engage in when it comes to legacy software). As far as Chris and Andrew are concerned, open-sourcing the game has secured its existence for at least another decade, and I tend to agree it will remain. Not only that, running a legacy MMO is simpler than ever before. Since porting the server from Windows to Linux (a completely unexpected development, according to the Kirmses), running a Meridian 59 server is affordable for any enthusiast — the server can quite easily run on a single Amazon AWS instance, or even a Raspberry Pi.

This low barrier of entry and low cost to sustain it means that, as long as there are players, there will be Meridian 59. As Andrew said, “if anyone shows up, we’ll keep the game running. I’ll keep it running… as long as I can get out of bed.”

Meridian 59 has proven over and over that it is nigh invincible. Not every game is this resilient to time and tide — in fact, precious few are. From my perspective, that is because Meridian 59 was never a business venture. It was a project born from an honest passion and a desire to create something that gave people joy. I’ll end here with a final quote from Chris that I think demonstrates why Meridian 59 has stood the test of time:

“Our goal at the beginning was to make the game and have people play it. The goal wasn’t to make a company out of it, the goal wasn’t to make money out of it. We wanted to have happy users playing our game… I mean, that’s something that’s kind of stuck with me my whole career… Build a platform where there’s a lot of happy users, and if you start from there and from there can build a business on top of that, great, but more important is, are you building something that’s providing value to people?”