An Ode to The End

17 years on, Metal Gear Solid 3’s geriatric sniper remains peerless

I like many, have a love-hate relationship with boss fights. This is largely due to their wildly varying quality both within individual games and across the medium as a whole. Boss fights can disappoint by being overly linear, too long, or too bland to match the story’s high stakes. We can look to the otherwise outstanding Doom Eternal for an example of this. The ‘Icon of Sin’ is a dull bullet-sponge that feels oddly removed from the arena the player is fighting in. The fight’s intensity and urgency is created by the spawning waves of enemies. The Icon is comparatively benign, barring some heavily telegraphed attacks. It might take time to down the beast, but it is only time. Cutting through the hordes of demons, and emptying a few rounds blindly in to the enormous target at the side of the stage whenever you have a free moment is all it takes to defeat the worst hell can throw at you.

I’ll cede that there is no exact science to a good boss fight. Epic battles, especially late-game or end-game ones, might suffer if the story has not adequately built things up for the player. Equally, perhaps not even the most engrossing plot can paper over generic, ‘shoot-the-glowing-weak-spot’ banality. Boss fights exist in an awkward limbo of needing to change things up from the regular gameplay, but simultaneously test the skills it has been drip-feeding the player throughout the game. Pairing this with placement within the game’s narrative, not to mention the subtle art of nailing a boss’ difficulty, and it’s easy to see why so many games struggle to create bosses that challenge and delight players in equal measure.

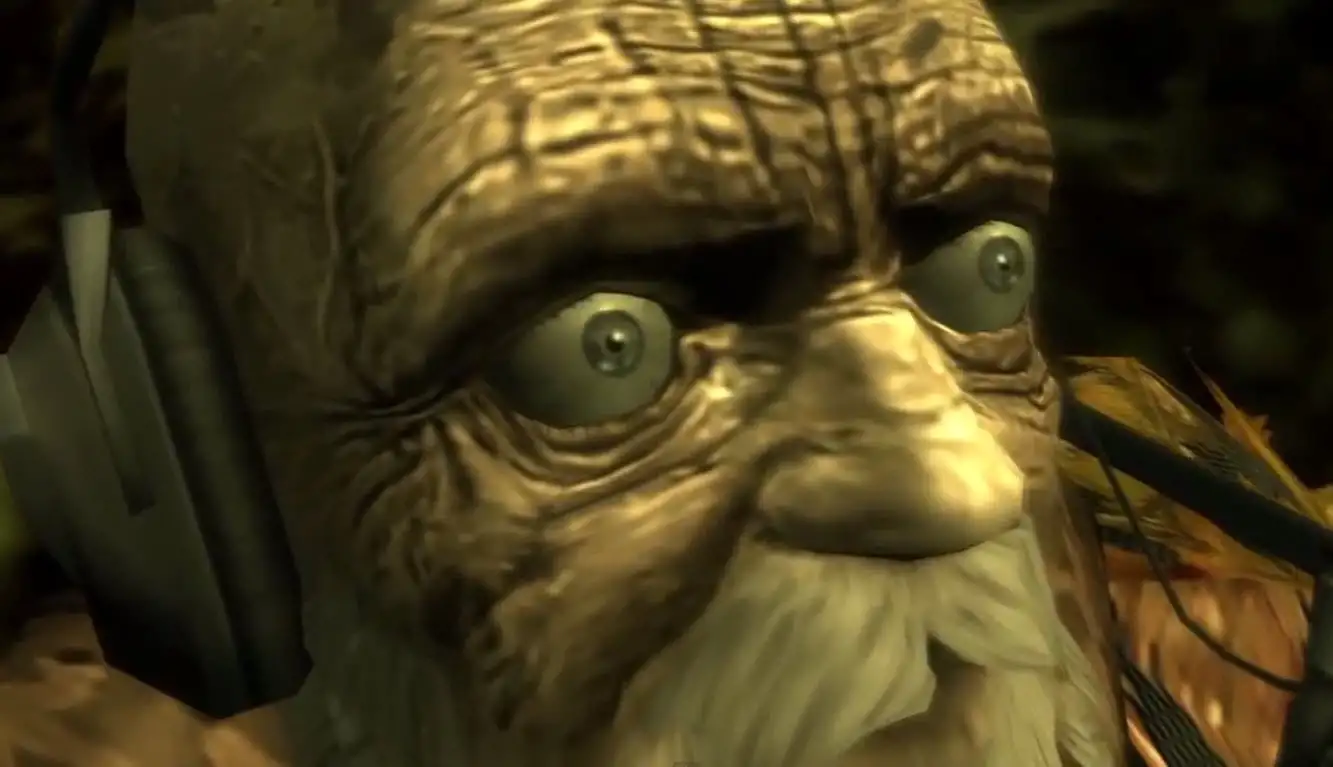

Let’s talk, then, about The End. Appearing in Metal Gear Solid 3, The End is a hundred-and-something year-old sniper with supernatural abilities that make him ‘the father of sniping’ and a fearsome member of the fabled Cobra Unit. He lives up to the billing: even on lower difficulties, The End punishes careless play severely. Loud noises, or impatiently running around the map instead of crawling, result in him fixing you with rifle fire. He moves quickly and quietly between forty sniping nests across three sections of the map, and his camouflage makes him incredibly difficult to spot. Finding him, let alone damaging him, can be plenty challenging.

Boss fights exist in an awkward limbo of needing to change things up from the regular gameplay, but simultaneously test the skills it has been drip-feeding the player throughout the game.

Already, we can see how The End transcends a lot of boss design cliches before you’ve even begun. His movements aren’t telegraphed on screen or on a mini-map. He doesn’t move between a small number of locations in a fixed or predictable pattern, or obviously reveal himself at timed intervals. Save for the glint of his rifle’s scope making him easier to locate, there is no obvious or simple weak-spot. There’s no text on screen or character shouting from the side about what to do. It is a rare boss encounter that begins with you alone and unable to see your foe, with no real hint as to how to go about defeating him. The first time I played MGS 3, I felt this loneliness: there was no tell-all radio call from Zero or EVA advising me on what to do next. I immediately hid in the grass, and furiously cycled through my inventory to find something that might help.

It turns out that there are a plethora of viable strategies to beat The End, all of which involve you thinking logically and making the best use of the tools at your disposal. Identifying the end can be as simple as whipping out your binoculars. The directional mic can also detect his somewhat heavy breathing. Thermal goggles can reveal his footsteps, provided he is on the move. If you’re really stuck, or especially impatient, you can deliberately fire off a couple rounds of an non-suppressed weapon, draw his fire, and have his position marked on the map for you.

Finding him is all well and good, but you still have to figure out a way to deplete either his stamina or health bar faster than he chips away at yours. Once again, The End is completely open-ended in this regard. Unlike bosses that might be immune to certain kinds of damage, almost any way you want to damage The End will work. Non-lethal strategies, such as CQC or the handkerchief will work just fine, though they come with the challenge of getting close to The End without him spotting or hearing you. Likewise, you’re free to fire off clips of your AK-47 from mid-range if you wish, but the window of time you’ll have before The End spots and pins you is short. The knock-back effect of his rounds make this an especially risky strategy. Almost anything will work, dependent on your skill, patience, and luck. On lower difficulties at least, it’s possible to ‘go loud’ and draw The End’s fire and simply chase him with a shotgun, using the thermal goggles to track his footprints if he ever gets too far away. That strategy might down The End in a matter of minutes. A more traditional approach might take an hour or more.

What’s fantastic here is almost every item the player has picked up thus far can be employed in some way to help. It’s not uncommon for games to include one-note, situational items, weapons or tools meant to tackle a specific enemy or puzzle. Games often place ammo drops right before boss rooms to signal a specific weapon being the optimal strategy. In MGS 3, it feels like the developers considered every reasonable avenue that a player might expect to be able to use the items they’ve amassed, and it allows for innumerable potential approaches. Non-lethal optional pickups like the cigarettes that spew gas or the handkerchief work well. The aforementioned directional mic is extremely helpful for detecting The End through sound. Rather than force the player into a fixed strategy, the game accounts for everything that the most thorough players might have picked up; while also catering to players who might have missed, say, the sniper rifle located off the beaten path a few areas prior, or are in general are prioritizing a quick play-through.

The End can be dealt with in other, easier ways, too, ways that reward the player’s attention to detail and creativity. In an earlier cutscene where other members of the Cobras are discussing the fact that The End is always sleeping, the player is tipped off that, seemingly whatever happens in your fight with him, it will be his last. The visual cues of the sniper’s advanced age, wheelchair use and constant tiredness seem at odds with the spry, eagle-eyed sniper giving you trouble an hour or so later. Father Time can indeed be your ally after all: if the player starts the fight, saves and quits, and waits a week, reloading results in a brief scene where Snake sneaks up on The End only to find him already expired. If you don’t want to wait a week (or don’t know where the date and time settings are on your PS2), you can still avoid the straight fight with The End if you so choose in another way. In the section immediately following the earlier referenced scene where The End is sleeping in his wheelchair, there is a tiny window where a perfectly timed and placed snipe will down The End, making the later fight a mere leisurely stroll through the Jungle. This one rewards players who’ve headed off the beaten path to acquire a sniper rifle, and those who notice that relatively subtle cue of The End’s health bar briefly appearing for as long as he is on screen.

In MGS 3, it feels like the developers considered every reasonable avenue that a player might expect to be able to use the items they’ve amassed, and it allows for innumerable potential approaches.

What strikes me about the fight with The End is just how adaptive the fight is to the player, particularly for a game this old. Beyond advancing your console’s clock, there’s no tactic that makes The End particularly easy or predictable. Going for a stealthy approach tests not only your skill but also your patience. Going loud might end much quicker, but you may also die a lot in the process or burn through precious food resources and medicines. The game lets the player try almost any strategy they wish, the only limits being their creativity and, again, their patience to actually see out that strategy. Metal Gear Solid 3 is also commonly a game where players give themselves self-imposed challenges, such as not using overpowered weapons or tools, or finishing the game completely non-lethally. The challenge of The End is only increased through these, but never becomes impossible. Unlike other games that rely on bosses that have barely a handful of workable strategies, The End remains a solvable puzzle even when the player places added constraints on themselves, which is nothing short of remarkable.

Throughout MGS 3, there are multiple memorable boss fights that employ the same design philosophies executed in The End’s. The Fury almost matches the knife-edge tension; The Pain has a breadth of moves that can be exploited and used against him. While almost all of them are excellent (I’ll nail my colours to the mast and say the duel with Ocelot is rote), none come together with the same intoxicating mix of atmospheric tension and player freedom the way The End does. He might be over a century old, and a relic of fifteen-year-old game design, but age hasn’t slowed him down one bit.