Aliens Among Us: EarthBound and the American Dream

EarthBound is praised for its quirky, nostalgic American setting, but something far more profound lies beneath its cheerful surface

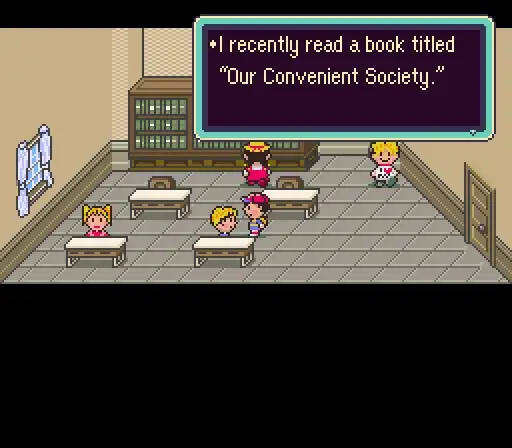

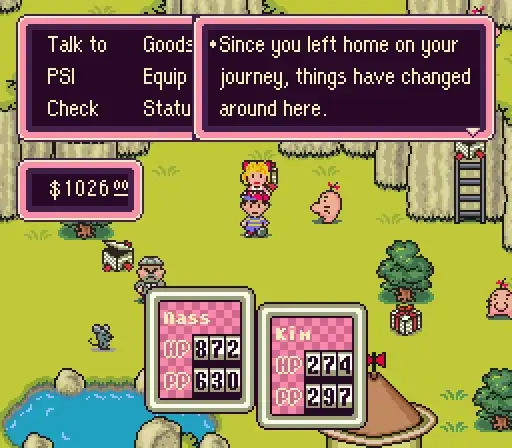

EarthBound might have been the weirdest role-playing game of the 1990s. While 99% of RPGs on the market had fantasy settings, EarthBound is set in the heart of nineties Midwest America, here called “Eagleland.” While most RPG protagonists wield swords, cast spells, and drink healing potions, EarthBound’s protagonist Ness is a kid in a baseball cap who wields a baseball bat, has psychic sci-fi powers, and eats hamburgers when hurt.

The currency is not gold found in treasure chests, but paper dollars withdrawn from ATM machines. The low-level quest isn’t defeating the goblins who invaded the castle, but a rough-and-tumble gang of youths who took over the local arcade. Much of the game’s soundtrack alludes to popular Beatles tracks. So there’s a lot of nostalgia in this game, to the point where mainstream game critics and fans alike wrote the game off as a quirky reflection of ‘90s American culture set to a generic “defeat the evil alien antagonist and save the world.”

But below the surface, there’s a deeper meaning. EarthBound, despite how idyllically American the setting is, is a pointed critique of the American Dream. It’s about coming to terms with the hidden evils buried underneath nostalgia and desire. The game wants you to think of it as uncomplicated nostalgia, but just as many American Exceptionalists view our history as about freedom, becoming wealthy, having a house and a dog and all that “American Dream” stuff, every so often the game throws in disturbing scenes to challenge that assumption. And it does this, literally atop an alien invasion plotline, to explore the complicated dynamic of cultural alienation in American society.

[EarthBound is] about coming to terms with the hidden evils buried underneath nostalgia and desire.

No game critics have investigated the role of the American Dream as a theme of EarthBound — the closest we’ve come is an early episode of Game Theory tying EarthBound to real-life social issues, including the 1992 LA riots, and the Angry Video Game Nerd’s reading of EarthBound as being about repressed evil, symbolized through the game’s final boss, the “alien” Giygas. “It’s as if Giygas isn’t really a thing, but more of an idea” the nerd says in his analysis, “Giygas is the vague embodiment of evil, or the devil itself, which makes this whole battle feel like an exorcism.” While both the nerd and Game Theory’s Matthew Patrick effectively delve into the game’s psychology and societal allusions, neither thematically make the connection between the game’s dark elements and its constant barrage of American imagery, which is crucial in fully appreciating EarthBound. This lack of critical attention could be explained in the debate within literary theory between New Historicism and “Old” Historicism.

Traditional historicism is a rich movement within literary criticism, investigating the ways in which literature acted as a direct reflection of history. Overwhelmingly, though, historicist criticism on literature carried the writers’ biases with it, viewing history as stable and unquestionable. Something similar is seen among historians who subscribe to American Exceptionalism. But why do we so frequently look at history this way? Well, as they say, history is told by the winners, in this case White America. Dominant ideologies form and prescribe what human experience was actually like throughout history. New Historicism, on the other hand, counters that approach, pointing out the multiplicitous tapestry of perspectives and experiences that contribute to historical events. If one group’s experience is seen as the broad-brush “real” interpretation of history, the New Historicists would argue that’s likely because of power. New Historicist critic Ralph Cohen writes that “state practices of colonization or deprivation of the rights of minorities or the denial of economic and social equality…are not forms of imaginary subordination” as they’re often purported to be.

And yet, so many Americans to this day believe in the universality of the American Dream. According to Cohen, dominant history readings are frequently products of repressing “the readiness of human beings to end the lives of others” — for many Americans, their entire cultural identity rests on the assumption that the American Dream lacks flaws. We don’t want to believe that our ways of living are suspect, whether because it would be inconvenient or altruistically depressing, and so we don’t believe. But for those victimized by the American Dream, Cohen argues “we cannot ignore the sense of alienation, perhaps even of personal oppression, that has bred resentment from actual situations and social practices.”

This speaks to the need for New Historicism to recover histories lost in dominant ideology, which often “leaves us incomplete knowledge of history.” However, the American Exceptionalist nostalgia reading of EarthBound, that “Old” Historicist reading, is easy and tempting, but below the surface is a much complicated historical picture many have missed. Works like EarthBound instead provides “fostered resistance to received histories. They have resulted in histories and theories marked by opposition to exclusion and marginalization.” EarthBound, then, is a New Historicist work that profoundly speaks to the alienation Cohen describes, and it does it by featuring actual space aliens.

This dynamic between New and “Old” Historicist ways of looking at the world is something EarthBound plays with to great effect. The inciting incident is outlandish and idealistic before turning subtly disturbing — the protagonist finds a mystical alien that looks like a bee, “Buzz Buzz,” at a UFO crash site, who gives this prophecy that three boys and a girl will defeat the “alien” Giygas. They’re then ambushed by a powerful alien Starman, who Buzz Buzz skilfully defeats.

One scene later, Buzz Buzz is anticlimactically crushed to death under the heel of self-absorbed wealthy socialite Lardna Minch, who holds a grudge against Ness’ family over an unpaid loan. Initially a gag, this seems to set the thematic tone for the rest of the game, this idea that desire, especially moral desire, must be negotiated against a materialism that permeates American culture. Buzz Buzz wants more than anything else to stop Giygas — he can defeat fearsome super-aliens, but he doesn’t stand a chance against Lardna Minch, the image of wealthy White America.

We see another small glimpse of America’s dark side in one nonsequitur immediately after Ness leaves home to start his journey. His neighbor invites him in, but Ness doesn’t seem to want anything to do with him, but immediately becomes interested when he hears about how the neighbor struck gold in his basement mine. Ness is led to a giant golden statue which looks like the Oscar award, and he “starts to get greedy thoughts…” before unceremoniously leaving. More on that later.

Over the course of the game, we see more disturbing, cognitive-dissonance inducing scenarios. Even though the antagonist is supposedly an apocalypse-inducing space alien, Ness’ opponents are almost always human. You might even forget for 95% of your play time that defeating Giygas, an “alien,” is the end goal. Ness, an actual child but one with money, finds himself routinely mugged by street toughs in broad daylight (defying RPG conventions of never being attacked in towns).

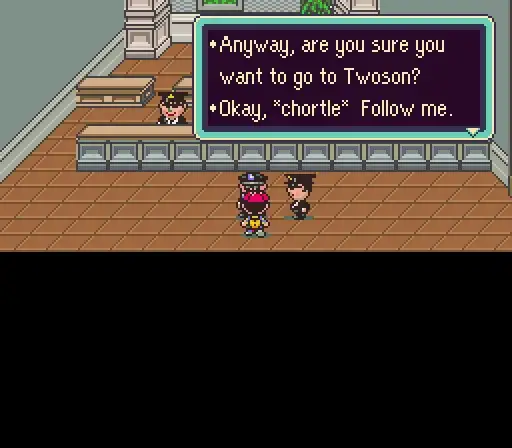

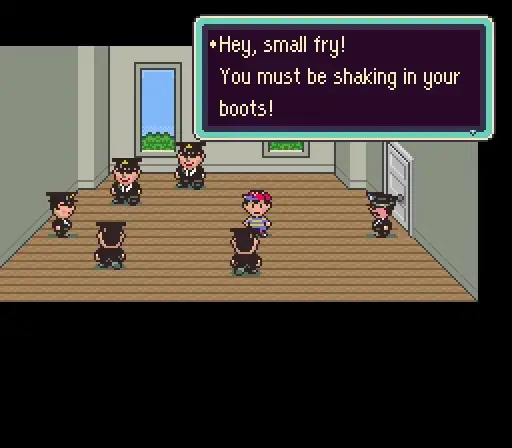

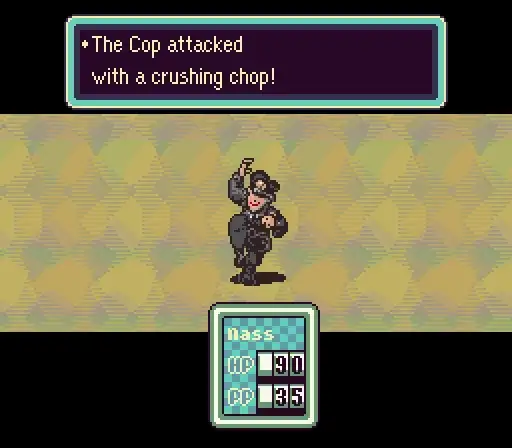

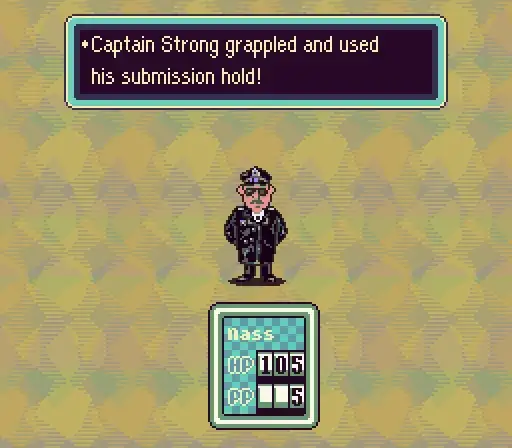

After saving everyone from the “Titantic Ant” terrorizing Onett, he is arrested en route to Twoson for trespassing. Then he’s physically assaulted without provocation by five police officers. And, yes, this game was somehow initially rated E for Everyone before finally being changed to T for Teen nearly two decades after publication.

It turns out better for Ness, who fights them off with his baseball bat (and for the player who came prepared, a healthy stash of hamburgers in the first aid kit), than it does for people in the real world. This entire scene is played for laughs, and it’s hilarious in a Kafkaesque sort of way that makes the player question why the cops would even think to violently assault a child for trying to leave town instead of escort him home, then be so wildly incompetent that five of them find themselves unable to win in a fight. One cop even says to an actual child who just beat up five cops, “You should join the police force!” as though violence is the only qualification of being a good cop. Ultimately, “Captain Strong,” the head of Onett’s police department, holds newfound respect for Ness and just lets him go, personally and extralegally opening the closed road to Twoson for reasons.

Sadly, this interpretation of the police as an explanation for the flaws of American society is only a little exaggerated. This game, set in ’90s America, was released in 1994, right at a time when all eyes were set toward police brutality in America. By this point, decades after the Civil Rights Act, many believed we were in a post-racism society. But as Game Theory points out, on March 3, 1991, four police officers were caught on video beating Black taxi driver Rodney King during what should have been a standard DUI charge. In addition to 53 baton blows, CBS reports that “King showed his injuries to reporters — the bruises, broken leg, and the scar from the stun gun which jolted him with 50,000 bolt shocks,” said CBS News correspondent Jerry Bowen a few days after the assault. This culminated in the 1992 LA riots protesting police brutality.

For many who watched the news during this time, during police killings of Michael Brown and Eric Garner in 2014, and George Floyd in 2020, and many of the other instances of police brutality in the past century, it posed an existential crisis. Is the history we’ve been taught really true? Did Martin Luther King Jr. speak on dreams and end racism is we know it? Is the American Dream fully, uncomplicatedly possible for all Americans? If Black Americans, but not White Americans, must worry about being brutally assaulted and/or killed for misdemeanor charges, neither of these can possibly be true. Just like that incident, EarthBound’s own police brutality instances get us to question whether America really is the land of prosperity it’s purported to be.

Of course, there are some differences between EarthBound’s police brutality and the LA riots. For one thing, Ness isn’t Black. However, the proximity between this game and that event and both situations depicting police brutality cannot be ignored. Moreover, later events of the game show careful attention and parallels to other racial issues.

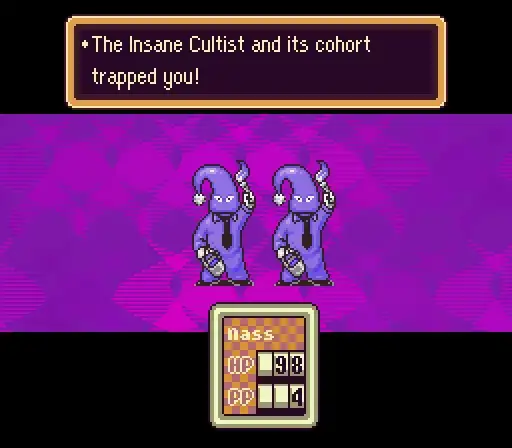

For instance, Ness finds himself entangled with the “Happy Happyist” or “HH” cult, which is literally the KKK. The only difference is their hooded sheets are blue. The sheets would likely have been white had it not been for Nintendo’s strict censorship polices.

Ness has to rescue another character, Paula, who has been coerced and captured by the Happy Happyists, who want to exploit her psychic powers. The HH worships the color blue (again, a product of Nintendo publisher meddling and can be read as White) and they’re seen painting everything in the village that color. Blue houses, blue cars, blue outfits, blue cows, blue everything. That’s metaphorical — their mission is to “paint everything in the world w̶h̶i̶t̶e̶ blue.”

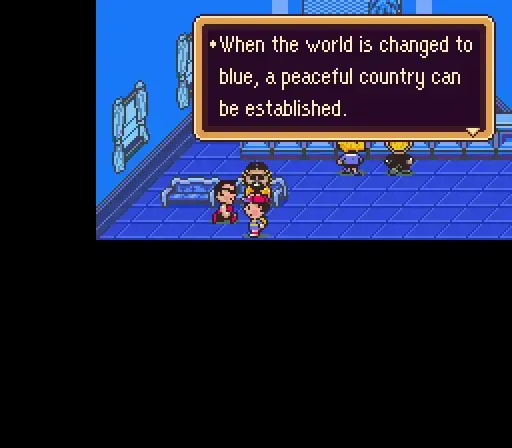

To do this, they use a statue, one that looks exactly like the one from earlier which made Ness feel greedy, which magically (on a symbolic level materially/culturally) enhances people’s desire for fame and fortune. This statue, then, is what helped brainwash everyone in the Happy Happyist cult to paint the world w̶h̶i̶t̶e̶ blue. It’s also what got Ness’ neighbor, who isn’t a cult member, material wealth. When Ness confronts the Happy Happyist leader, who tells him HH is what will return the world “to a happy and peaceful society” and asks Ness, “Will you be my right-hand man?” You can say “Yes” or “No” (You’re supposed to say “No” to progress in the story), but it’s made out as a tempting thing for Ness.

Man, this sure complicates the American Dream. It’s supposed to be this simple, nostalgic thing, but Ness’ ways of getting the statue, which can be read as achieving material success, all involve doing bad things. This is at its worst in w̶h̶i̶t̶e̶ blue supremacy, but as we saw with Ness’ neighbor and Ness himself, despite neither being w̶h̶i̶t̶e̶blue supremacists, this kind of greed can also manifest itself in ways that appear benign, but are still harmful. Ness’ flaw, greed, in this scene is tied to the KKK, which says something horrifying about American culture. Is it as equal as we think? What are we willing to do to get the American Dream?

Ness finds himself entangled with the “Happy Happyist” or “HH” cult, which is literally the KKK.

I just want to remind everyone that these disturbing glimpses are supposedly the exception — the aesthetic of the game we constantly see is diners, white picket fences, and simple dreams, but clearly there’s something underneath it that’s disturbing, and that’s deliberate.

This bothers Ness so much that at the end of the game that his inner strength (qualified by in-game stats) is stunted by greed for the entire game, and this is cured only by self-reflection. He psychically enters his own subconscious, and it’s pretty trippy. And what does he come cross but the greed statue from earlier?

Only in confronting his nightmare, greed, does he get the literal stat boosts he needs to be viable in-game. His health jumps from probably 400-ish (depending on how much the player level-grinded) to over 700, and he gains several experience levels in a cool narrative moment articulated by gameplay mechanics.

The music track that played during the battle against the K̶K̶K̶ HH leader is “Otherworldly Foe,” which is usually partitioned for the actual aliens Ness comes across. Maybe there’s something pernicious that feels alien underneath the American Dream, which underlies and infects it, and that really speaks to the cognitive dissonance we have to confront in our historical visions of America. We have to come to terms with how America is materialism, materialism creates greed, and greed creates evil. If this is true, then the “alien” was human all along.

This is true on both a metaphorical and literal level. The fight against Giygas, supposedly an alien, turns out to be a fight against the human capacity for evil baked into our culture. That’s why we spend most of the game fighting gangsters, corrupt cops, and the Happy-Happyists, instead of the actual aliens who crash-land on Earth.

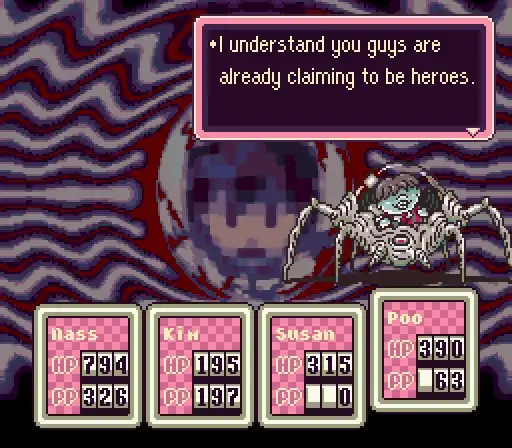

The final boss fight against Giygas itself is a total mindscrew. You have to see it to fully understand. But the game is always asking the question about whether Gigyas is really an alien or whether the fight is a symbolic existential crisis about human evil. Giygas is from another planet, but raised by humans, simultaneously human and alien.

The image of Gigyas is a total Rorschach test — it starts out having Ness’ face, but then it changes. It could be a human fetus, it could Edvard Munch’s “Scream” painting, or it could be the screaming face on the cover of Pink Floyd’s “The Wall.” (Again, rated E for Everyone, folks).

All of these are reflections of human experiences, and Rolfe argues we can read Giygas as symbolizing humanity’s latent capacity for evil. Giygas delivers strange dialogue like “I’m h…a…p…p…y” but also “It hurts,…it hurts,” “It’s not right…not right…not right” and “…I’m so sad….” Perhaps that’s the natural outcome of the American Dream — trying to be happy, feeling hurt in hurting people, which is indeed not right, and then feeling sadness and despair after realizing there’s a void which materialism cannot fill. But it’s such a permeating force that Ness’ cultural motif weapon, a baseball bat, cannot damage him, and healing burgers can only delay the inevitable as Gigyas delivers his inexplicible attacks — After all, “You Cannot Grasp the True Form of Giygas’ Attack!

Instead, a cognitive bias buried to the subconscious can only be alleviated by being cognizant of the problem — Paula, using her psychic powers, speaks to the people of Earth and gets them to pray to stop Gigyas. If the problems of the American Dream come from only recognizing exceptionalism, the only way to confront it is to get as many people as possible to be aware that Gigyas, the representation of human evil, needs to be stopped. That knowledge, and only that knowledge, can provide the means for confronting unconscious evil.

EarthBound is set in ’90s America for a reason. It’s the moment in time where we were just far enough in equality movements that we just started tricking ourselves into thinking inequality was over, and the American Dream was attainable for everyone, only to have those hopes dashed by an increased cultural awareness due to the LA riots, AIDs crises, etc… It wasn’t the American Dream that was our antidote to inequality, it was the cause of it. It’s materialistic and it gets us to be greedy. We value ourselves over others, and doing the right thing is hard. We see that both in EarthBound and the real-world historical context it responds to. Therefore, its lesson is ours. We need to look beyond the American Dream as this uncomplicated, exceptionally good thing — a lot more in history and culture was going on to challenge that idea. But by recognizing these problems, the alien becomes human, and together people can confront the evils buried under the surface.