A Story That Can Only Be Told Through a Game

Breaking down Goodbye World's powerful metafictional narrative

I’ve played a lot of indie games, but few have had quite the impact on me that Goodbye World has. Released in late 2022, Goodbye World follows Kani, a game designer and programmer, and Kumade, a pixel artist, along their journey as indie game developers with a passion for retro games.

Goodbye World weaves together simple but compelling platforming gameplay with a masterful narrative. Although only a short, two-hour experience, the game has left me with a story and a message that I’ll be thinking about far past the credits screen.

From the game's opening, the developers of Goodbye World communicate their love for retro, 8-bit games alongside a worry that it is becoming harder and harder to find success with making them, since the scope and fidelity of modern games has rapidly increased. This worry is brought to fruition when our protagonists decide to professionally make games together after graduating from college and face the harsh reality of being indie.

The Core Gameplay Loop

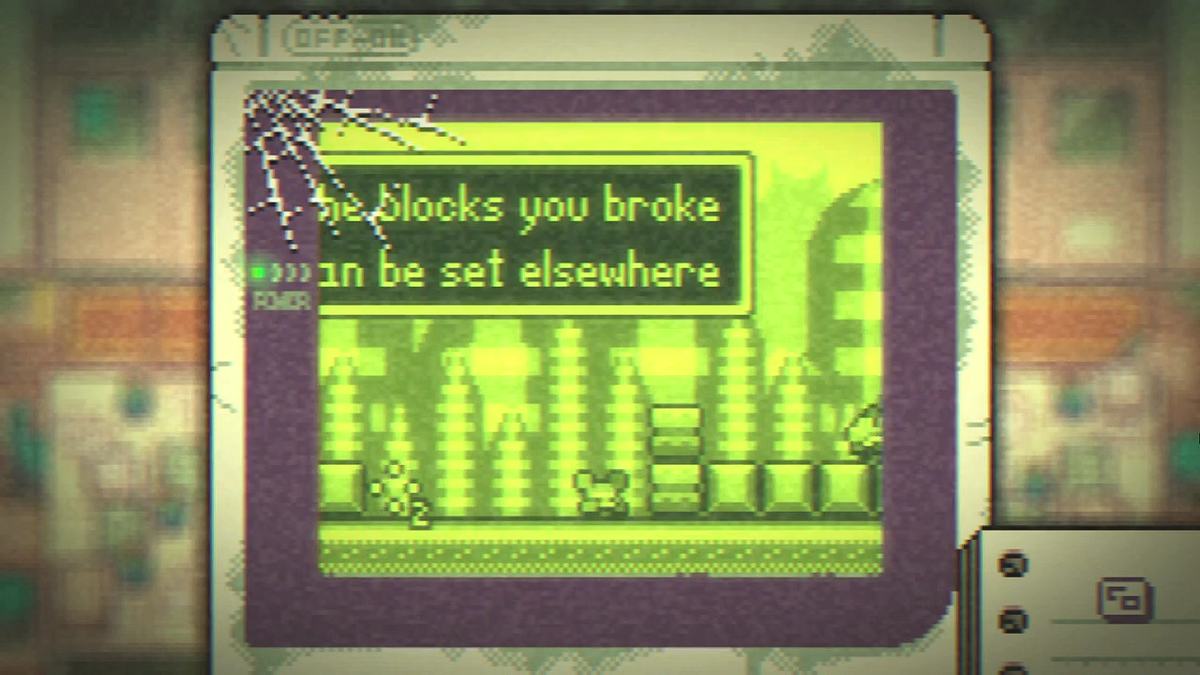

Before jumping into the story, I'll first break down the gameplay since it is essential to the narrative. Goodbye World is told through 13 chapters. Each chapter begins with a level from a platformer minigame called Blocks, played from what appears to be Kani’s perspective on her Game Boy, followed by a cutscene.

(Left) Blocks gameplay, (Right) cutscene from the first chapter. Source: Author.

Although playing on Kani's Game Boy adds an extra layer of immersion, at times the platforming gameplay interrupts the pace of the story. This is exacerbated by the fact that the levels in Blocks are actually quite challenging. Centered around the mechanic of being able to pick up and place down blocks with a cursor, Blocks incorporates challenging puzzles with platforming precision and only gives you a few tries before a game over. These levels can be replayed as many times as you want after completing the game, but during the chapters in the story, having only a few lives to work with can be frustrating.

To move past a level and progress to the cutscene players must either beat the level or run out of lives. When players are able to complete levels, there are few problems other than the slight interruption in narrative pacing. However, when running out of lives, even after progressing to the cutscene, my mind stayed focused on the Blocks level, thinking about how to beat it on my next attempt or feeling frustrated that I missed that one jump for the third time.

The main problem here is a lack of player control or accessibility options, which would give hardcore players the ability to complete levels at their own pace while preventing narrative-focused players from getting stuck. One solution would be to give players unlimited attempts, but enable an option to skip the level after failing 3 attempts.

You might be wondering, then why include Blocks in the game at all? As you will see later, despite its shortcomings, Blocks actually adds much to the game's overall narrative, especially at its climax. And on its own, Blocks in every way accomplishes the developers' goal of communicating the beauty of retro games. Even with just one unique mechanic and a simple art style, the design of every level was engaging and each platforming puzzle provided a welcome challenge.

The Narrative

One of the core questions this game explores is whether developers should design games that they love or design games that will sell.

After going indie, Kani and Kumade release several games with little success. They realize that to become successful, they must make bigger games, develop for newer platforms, and create higher fidelity art. But as they go down this path, Kani begins to stop enjoying the game development process, faces an onslaught of mental struggles, and loses sight of why she loved making games in the first place, which pushes Kumade to leave the team.

Spurred by Kumade’s departure, Kani does some reflection and remembers the games she loves, and the reason why she first started making games. This leads her to “make something [she] actually wanted to make,” a new game project, now solo-developed, that goes back to her roots. It has simple 8-bit graphics, is made to run on retro consoles, and goes by the name Blocks.

But unfortunately and perhaps expectedly, Blocks does not sell. Publishers are unable to look past the game's target platform and art style and turn Kani away without even playing Blocks a single time, while questioning her skills as a developer. Dejected and demoralized, Kani turns back to the one person she knows believes in her work.

A Climax for the Books

When Kumade later visits Kani's apartment for the first time in months to try out Blocks at Kani’s request comes the most magical part of the game, its climax. When this final scene begins, the black bars that had framed every cutscene in the game so far slide away, and for the first time, the player is able to have an impact on the real world outside of Blocks, with the ability to control Kumade.

Implementing different levels of player agency and removing constraints like the black bars can give designers a lot of control over when players are engaged and how engaged they are. Goodbye World uses this masterfully to emphasize its ending and draw in the player's attention.

While exploring the room, players will take note of its emptiness and the ominous sliding door, opened to expose the balcony. As they realize the possibility of the worst outcome occurring, they are reminded of foreshadowing that may have begun even before the game was opened, in its title, Goodbye World.

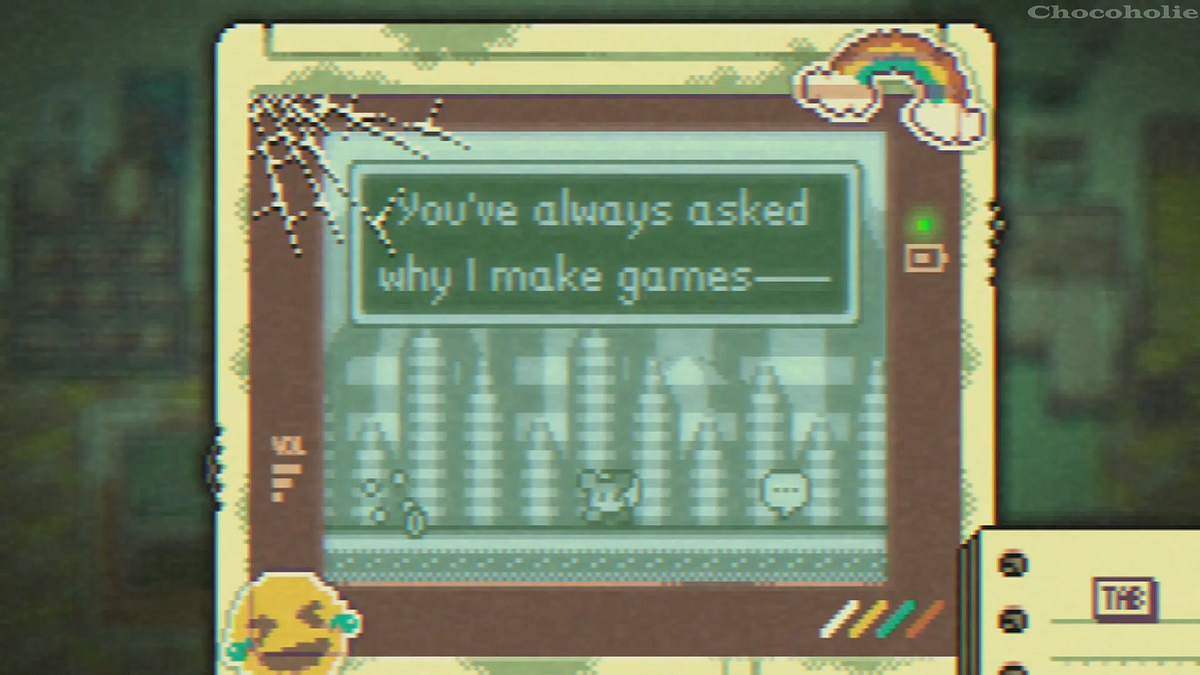

When Kumade picks up the Kani's Game Boy, which has been left on her desk, the game reveals Blocks' final level, which contains a message from Kani to Kumade, who has decided to finally answer the question that Kumade has been asking her for years: “Why do you make games?” This message is beautifully conveyed through the use of Blocks as a medium.

Through tutorial prompts that have been repurposed into dialogue boxes, Kani tells Kumade that developing Blocks was her way of rediscovering her passion, and in doing so, she realized the reason she makes games is straightforward, but something she lost sight of — simply because "it's fun." Although Blocks had poor reception, Kani had fun making it and she insists that she had even more fun making games with Kumade, which leads her to end the level asking Kumade if she wants to join hands once again to finish developing Blocks together — “Can we … Try again?”

This urges the player to input the command to restart a level, serving as a metaphor for Kani and Kumade restarting their joint game development career; after pressing restart, the game's credits begin to roll.

But what happened to Kani? How will they try again? What's next? After the credits roll, it is revealed that the answer is in this game itself, Goodbye World.

The game Goodbye World is the latest release by the game developer duo, Kani and Kumade. It is the full realization of Blocks on modern consoles, which incorporates the retro-feel of Kani's original platforming gameplay and simple graphics while adding in a gripping narrative based on a real story, alongside Kumade’s beautiful pixel art in its cutscenes. Kani did not commit suicide; all the tension and misleading foreshadowing was Kumade’s way of bringing in elements that Kani mentioned she wanted to incorporate into their games when they first met: plot twists, metaphysical ideas, and the unexpected death of a protagonist.

Conclusion

Goodbye World is my first experience with metafiction in a game, with players interacting with the actual product that the protagonists of the game create. My gradual realization of this metafictional quality, first with Blocks being Kani's solo-project then with Goodbye World itself being the full realization of that project with Kumade back on board, was completely unexpected yet made so much sense. It was clear that despite its disconnect with the cutscenes, the Blocks gameplay at the beginning of each chapter was Kani and Kumade's way of staying true to the retro games that they loved, down to even the context of playing it on a Game Boy.

While conveying some of the harsh realities of the game industry, where indie developers often have to cater to the market at large in order to gain the support of a publisher or to even just make a net profit, Goodbye World inspires those of us in the industry to never lose sight of what inspired us to make games in the first place, and to be aware of what we've lost when this inspiration is gone.